Chapter 11 Physiotherapy and occupational therapy in the hypermobile child

Clinical presentation

Many children have hypermobile joints, however only a percentage of those will suffer from symptoms. JHS is diagnosed when hypermobility becomes symptomatic and all other causes of the symptoms are excluded. Laboratory tests may be necessary to rule out other more serious conditions which may have similar symptoms, such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and other inflammatory conditions, the other forms of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome (Chapter 1). Findings of marked hyperelastic skin, herniae and lenticular abnormalities are not usually seen in JHS, but relatively easy bruising and poor wound healing may be seen, indicating some overlap with these defined genetic conditions (El-Shahaly & El-Sherif 1991).

Children may present to an orthopaedic physician, rheumatologist, paediatrician or physiotherapist with any of a wide range of traumatic or non-traumatic pain complaints and other associated symptoms (Table 11.1). These children typically lack the positive laboratory findings found in rheumatological conditions and rarely develop any positive changes in radiological investigations. Occasionally mild swelling or puffiness, and more rarely joint effusions, may occur at very hypermobile joints, but usually only lasts for hours or, very occasionally, days (Kirk et al 1967, Scharf & Nahir 1982, Russek 1999). The prevalence of symptoms is variable however, being more common in the lower limbs.

Table 11.1 Common presenting symptoms in JHS in children

| Main Presenting Symptom | Main Areas Affected |

|---|---|

| Pain | Joints |

| Muscles | |

| Headaches | |

| Abdominal | |

| After physical activity | |

| Night-time pain | |

| Fatigue | |

| Muscle weakness | Grip |

| Hip abductors | |

| Hip extensors | |

| Inner range quadriceps | |

| Plantar flexors (ankle) | |

| Joint symptoms | Clicking joints |

| Mild and temporary effusion | |

| Flat feet | |

| Subluxations | |

| Sprained joints (ankles) | |

| Chondromalacia patellae | |

| Skin | Easy bruising |

| Poor skin healing | |

| Skin stretchiness increased | |

| Papyraceous scars | |

| Stretch marks | |

| Developmental changes | Congenital dislocated hip |

| Delayed walking | |

| Reduced co-ordination | |

| Gastric reflux | |

| Hernia | |

| Changes to gait | Poor heel/toe action |

| Flexed knees | |

| Flexed internally rotated hips | |

| Positive Trendelenburg action | |

| Tiptoe walking |

There have been many scoring systems devised for measuring or defining hypermobility (Chapter 1), with the Beighton 9-point scale being the most popular (Beighton et al 1973). One intrinsic difficulty associated with the Beighton scale is measuring ranges of passive movement; the observed range depends upon the force applied to the moving part, which may vary with the enthusiasm of the examiner and the pain threshold and co-operation of the child (Silverman et al 1975). In addition, the scale only samples a few joints and focuses more on the upper limbs. As symptoms are more common in the lower limbs in children it is good practice to assess all joints for hypermobility initially in order to establish the degree of hypermobility, i.e. global or localized, as this will guide the treatment programme.

The Beighton scale forms part of the Brighton Criteria, a set of classification criteria for diagnosing JHS (Grahame et al 2000), which although not yet fully validated in children, is showing good potential and becoming the most commonly used measure (Chapter 1).

There are other recognized conditions that are closely linked with hypermobility in children.

Anterior knee pain

There is a significant association between anterior knee pain and generalized joint laxity and, in addition, it is recognized that hypermobility may be a contributing factor in the development of chondromalacia patellae. This can cause a variety of difficulties, including muscle wasting (particularly the quadriceps) and pain in the hips and ankles, and can lead to associated flat feet and backache (Al-Rawi & Nessan 1997).

Growing pains

It is believed that ‘growing pains’ or ‘benign paroxysmal nocturnal leg pain’ are related to generalized hypermobility (Maillard & Murray 2003). The pain is thought to be due to periods of unaccustomed excessive activity (such as after an intensive PE lesson) in those predisposed by underlying hypermobility with associated muscle imbalances and inefficiencies. It is very common for children with JHS to suffer pain at the end of the day and during the night, especially after a physically active day and the pain is more likely due to muscle spasm resulting from overuse of weak muscles and not due to ‘growing’ at all.

Motor development delay and dyspraxia

In the very young child, hypermobility may be detected with evidence of delayed motor development and a degree of clumsiness (Moreira & Wilson 1992, Davidovitch et al 1994). There is said to be a higher incidence of both gross and fine motor delay in children that are hypermobile, even in the absence of an identified neurological deficit (Jaffe et al 1988, Tirosh et al 1991). However, the motor delay is usually self limiting if hypermobility is the only cause and will improve either spontaneously or with a motor development rehabilitation programme. A number of parents of hypermobile children do report ongoing clumsiness in their children well into later childhood and beyond.

This is a difficult area as there is a considerable overlap between dyspraxia and JHS. The most common shared symptoms are those of impaired co-ordination, balance and proprioception. Many children who have a diagnosis of dyspraxia are also found to be hypermobile. It may be sensible to consider the diagnosis of dyspraxia and JHS along the same spectrum of conditions (Kirby & Davies 2007, Sugden et al 2008).

Chronic pain syndromes

Fibromyalgia, a syndrome of diffuse muscle and joint pain diagnosed by the presence of 11 or more out of 18 specific tender points, although most common in adults, has been reported to cause diffuse musculoskeletal pain and fatigue in children (Gedalia et al 2000). Hypermobility has been shown to be a significant feature of this syndrome too, with studies showing an incidence of hypermobility in patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia of between 14–81% (Gedalia et al 1993) (Chapter 5).

Other pain syndromes, such as CRPS, have also been linked with hypermobility and up to 80% of children with CRPS are also hypermobile (Mato et al 2008).

Fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome

Fatigue is also a very common feature in children with JHS and it can present in several ways. It can be global, affecting the whole body, or it can be specific, affecting specific muscle functions. Both need to be considered as a symptom (Chapter 6.1).

Children with JHS will often report difficulty in walking any distance due to tiredness and aching and they will also report that they need to get to bed early and will wake late and will often not feel rested after the night’s sleep. This pattern is also common in children with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). However, in CFS the fatigue will dominate their life and prevent most normal activities. CFS, characterized by unexplained fatigue that lasts for at least 6 months together with a constellation of other symptoms (Dinos et al 2009), has been associated with joint hypermobility. Barron et al (2002) found joint hypermobility to be more common in children diagnosed with CFS when compared to otherwise healthy children. However, a study on adolescents was less clear cut, finding higher skin extensibility in those diagnosed with CFS, but no difference in joint mobility, Beighton score or connective tissue abnormality when compared to a group of healthy adolescents (van de Putte et al 2005). In common with dyspraxia, it is the authors’ opinion that JHS and CFS should be considered on the same spectrum of conditions, because it is often unclear where one condition starts and the other finishes (Acasuso-Diaz & Collantes-Estevez 1998, Gedalia et al 2000).

There is no evidence to suggest, however, that JHS is linked with more serious conditions of the cardiac system, bone, skin or eyes (Mishra et al 1996, Grahame et al 2000). Although the incidence of ‘pulled elbows’ has increased due to children participating in more physically demanding sports, and there are reports of a link between hypermobility and ‘pulled elbows’, a study by Hagroo et al (1995) found no evidence of an increased prevalence of hypermobility in children with pulled elbows.

Prevalence

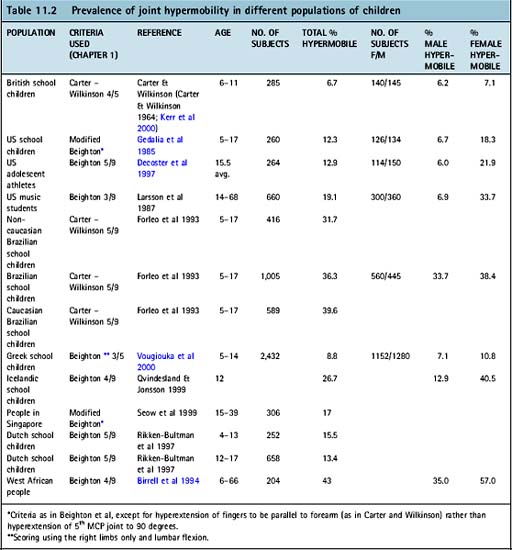

The reports of the prevalence of hypermobility must be viewed cautiously because of the variability in the measurement criteria used. Joint hypermobility has been reported in 6.7–43% of children depending upon age, ethnicity and criteria for assessing hypermobility (Table 11.2). The prevalence is higher in females, being between 7.1–57% compared to 6.0–35% in boys (Gedalia et al 1985, Decoster et al 1997, Russek 1999, Kerr et al 2000, Vougiouka et al 2000). Given the high proportion of subjects documented as ‘hypermobile’ in some studies, it is clear that the different systems of assessment have major limitations in defining a cohort at significant risk of musculoskeletal problems in different populations. Hypermobility is also more prevalent among Asians than Africans and more prevalent in Africans than Caucasians and decreases with age (Kirk et al 1967, Cheng et al 1991, El-Shahaly & El-Sherif 1991, Birrell et al 1994, Acasuso-Diaz & Collantes-Estevez 1998, El Garf et al 1998, Hudson et al 1998, Russek 1999) such that far fewer adults are hypermobile compared to the number of hypermobile children.

Assessment

Subjective examination

Pain

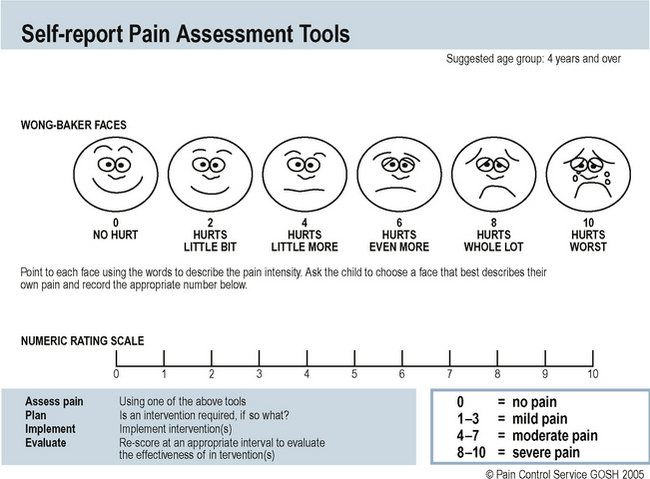

A body diagram can be used to record the pain distribution with a suitable measure of pain intensity, such as a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), which is less subjective if the child is over 7 years old, or a ‘Happy Face Scale’ (e.g. Wong-Baker Faces, Wong et al 2001) (Fig. 11.1) or ‘ouchometer’ for younger children. Children with JHS will often present with painful joints and muscles that are worse in the evenings, after physical activities, and may wake them at night-time. The pain only occurs after an activity and not during it, which makes it difficult for the family to feel they can limit the activity to avoid the pain. It is worth spending time taking a good history of the pain, since this will help ensure that full understanding of the pain picture is established and it also reassures the family that they have been heard fully regarding their child’s pain.

Fig. 11.1 Happy faces assessment of pain.

From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, ed. 8, St. Louis, 2009, Mosby. Used with permission. Copyright Mosby.

In JHS there is also the issue of the child developing a downward spiral of pain symptoms and this should be broken to avoid continuation of symptoms (Fig. 2.10). This idea should be explained to the family and from the assessment the relative proportion and timing of the rest periods and active periods should be defined. It is also important to ascertain when the episodes of pain occur, for example, always at weekends requiring the child to recover during the week instead of attending school because of the pain. This should be discussed as it will ensure the ‘pacing programme’ and returning to normal activity is appropriate.

Previous experiences of pain the child has had or personally observed before should be noted, because this may have an impact upon their coping mechanisms. A child’s coping mechanisms can be adversely affected by their observations of another member of the family who suffers from chronic pain (McGrath 1995). An assessment by a clinical psychologist often identifies factors which compound the underlying cause of pain in such children and families (Malleson & Beauchamp 2001).

Back pain in children may require thorough investigation and assessment. However one of the most common differential diagnoses is hypermobility (Scharf & Nahir 1982, Grahame 1999). The hypermobility may affect the whole spine or a specific area only and be related to a particular physical activity, poor posture or carrying heavy school bags. It may result in an ‘s’-shaped posture with an increased curve in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar regions. The pain is often due to acute muscle spasm and if not managed appropriately in the early stages may result in chronic back pain, continuing poor posture and the associated difficulties these bring.

Back pain tends to affect adolescents more often than young children. Acute disc prolapse, as well as early degenerative osteoarthritis, need to be considered, though these are extremely rare. If the pain is severe, other diagnoses need to be considered, such as spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis or pain amplification syndrome, all of which are more likely in hypermobile subjects. Idiopathic scoliosis is also linked to hypermobility, and although this is often functional, and not pathological, it should be taken seriously and monitored closely, with a comprehensive central core stability and strengthening programme prescribed (Chapter 10).

It is also important to ask about headaches and abdominal pain, because both are common in children with JHS. Headaches are usually due to muscle spasm in the neck, affecting the trapezius muscle, and producing a frontal headache, while abdominal pains are linked to cramps in the gut, which is commonly known as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (Chapter 6.2).

Fatigue

Children with JHS and chronic pain often have problems with generalized tiredness and have difficulty keeping up with their peers (Engelbert et al 2006). This may manifest as the need to sleep and rest more often or may present as a reluctance to walk any distance or play physically for any period of time. There are useful assessment questionnaires that can be used to help measure levels of fatigue, such as the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PEDSQL) Multidimensional Fatigue Scale which was designed to measure fatigue in patients aged 2–18 years (Varni & Limbers 2008).

Skin

Stretchy skin can often be an indication of hypermobility (Chapter 1), and may be associated with easy bruising and poor skin healing. Stretch marks are also more common in adolescents with hypermobility and become apparent during the growth period. There is a group of children with JHS/EDS who have more stretchy skin than normal and who often have a ‘doughy’ feel to their muscles. These muscles are often significantly weaker and more difficult to strengthen. Once strengthened they also, unfortunately, lose strength quickly after completing a training programme unless exercise is continued.

Co-ordination

Children with JHS are often clumsier and less co-ordinated than other children. They generally have poor balance and co-ordination and often fall over a lot and bump into different objects. This is thought in part to be due to reduced proprioceptive acuity in the joints, particularly at the extremes of the movements (Mallik et al 1994, Hall et al 1995) (Chapter 6.4). This may affect their ability to play sport effectively, to cut up food and manage other fine motor tasks such as buttons and zips.

School

Often children with JHS have difficulties with writing, affecting both speed and neatness, and this will have an impact on their performance abilities (Chapter 12.2).

Objective examination

Muscle strength

In a child with hypermobility it is important to assess the strength of the muscles surrounding a hypermobile joint, as well as the stamina of the muscles in the limb and trunk and the general stamina of the child. It is important for good control and stability of the joints that the muscles surrounding the joints have full strength and normal endurance, especially into the hypermobile range. If this is not the case then arthralgia and muscle fatigue are likely to occur with prolonged activity. The risk of subluxation of joints, although rare, is increased when muscle strength and control are not optimum. Muscle strength can be measured using either the Oxford Scale, or the expanded 11-point scale (0–10) (Kendall et al 1993) or by using myometry.

Stamina and fitness

Children with JHS are usually generally unfit and have very poor stamina and improving these will be an important part of a treatment programme. Stamina is often assessed subjectively, but the ‘6-minute walk test’ (Nixon et al 1996, Garofano & Barst 1999, Boardman et al 2000, Hamilton & Haennel 2000, King et al 2000, Pankoff et al 2000) is a better objective measure. This test requires the subject to walk as fast and as far as they can in 6 minutes. If they are unable to manage 6 minutes then the distance covered and the time taken are recorded.