CHAPTER 5 Physical Activity, Smoking Cessation, and Weight Loss

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

The World Health Organization has defined lifestyle as “a way of living based on identifiable patterns of behavior which are determined by the interplay between an individual’s personal characteristics, social interactions, and socioeconomic and environmental living conditions.”1 To promote health and improve clinical outcomes in a variety of chronic conditions, including chronic low back pain (CLBP), health care providers increasingly recommend interventions aimed at addressing lifestyle.2–4 Modifiable lifestyle risk factors are often nutritional or physiologic in nature, and interventions to address them commonly include general physical activity, smoking cessation, and weight loss. There are numerous types of interventions commonly used for modifiable lifestyle risk factors. For physical activity, these include walking and jogging, swimming, or cycling. For smoking cessation, these include “cold turkey,” nicotine patch or gum, and group or cognitive behavioral approaches. For weight loss, these include calorie restriction, food-type restriction, and medically supervised diets.

History and Frequency of Use

Although health care providers have long sought to improve their patients’ health through education and advice on general lifestyle modifications, this has generally depended on the availability of evidence to support an association between a risk factor and a particular health condition. The relationship between low back pain (LBP) and physical inactivity is likely complex because there is evidence suggesting that either too much or too little activity may be associated with LBP.5 However, there exist numerous potential confounders as many studies on this topic have occurred in an occupational setting.

For example, although physical activity such as repetitive lifting or twisting has been associated with LBP, this was likely confounded by high job dissatisfaction and low education.6–8 When examining recreational rather than occupational physical activity, many studies have reported that general physical fitness appears to lower the incidence or severity of LBP.9,10 Several hypotheses have been offered for a possible association between LBP and smoking, including repeated microtrauma from chronic cough leading to disc herniations, reduced blood flow to the discs and vertebral bodies leading to early degeneration, and decreased bone mineral density leading to vertebral body or end plate injury.11–13 Systematic reviews (SRs) have reported that 51% to 77% of epidemiologic studies found a positive association between smoking and LBP.14–16 Although a causal link between obesity and LBP appears intuitive because of additional weight on load-bearing spinal elements and altered biomechanics leading to excessive wear and early degeneration, evidence to support such hypotheses is lacking. An SR of 65 epidemiologic studies reported that only 32% found a positive association between obesity and LBP.17

Little is currently known about the prevalence of lifestyle modification counseling among spine providers. A cross-sectional study of 52 consecutive patients presenting to an academic spine surgery clinic reported that despite an increased prevalence of morbid obesity (body mass index greater than 30) compared with the general population, less than 20% had received counseling about lifestyle modification from their primary care physicians.18 It has been reported that chiropractors commonly offer preventive care services, including smoking cessation, weight-loss programs, fitness counseling, and stress management to their patients, including those with CLBP.19

Procedure

Physical Activity

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, regular moderate-intensity activity is sufficient to produce health benefits in those who are sedentary.20 Health care providers should recommend that adults engage in 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity 5 days per week, or 20 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity 3 days per week. Moderate-intensity activity burns 3.5 to 7 calories per minute and includes such activities as walking briskly, mowing the lawn, dancing, swimming for recreation, and bicycling (Figures 5-1 through 5-3). Vigorous-intensity activity burns greater than seven calories per minute and includes such activities as high-impact aerobic dancing, swimming continuous laps, or bicycling uphill. Regardless of intensity, patients should burn the recommended 1000 calories per week. To promote physical activity, patients need to be encouraged to set realistic personal goals, gradually increasing the length and intensity of activity, and varying the type of activities to remain interested and challenged.

Smoking Cessation

According to the American Cancer Society, smoking cessation involves four steps: (1) making the decision to quit; (2) setting a quit date and choosing a quit plan; (3) dealing with withdrawal; (4) staying “quit” (Figure 5-4).21 The decision to quit smoking must originate from the patients, who are more likely to succeed if they: (1) are worried about tobacco-related disease; (2) believe they are able to quit; (3) believe that benefits outweigh risks; (4) know someone with smoking-related health problems. The quit date should occur within the next month to prepare appropriately and not delay much further, and might be selected for a special reason (e.g., birthday, anniversary, or Great American Smokeout, which occurs on the third Thursday in November) (Figure 5-5). Family and friends should be informed of the quit date, which may require modifying activities previously associated with smoking (e.g., coffee or alcohol use). Although nicotine substitutes can reduce physical symptoms of withdrawal, they should be combined with a plan addressing psychological aspects of quitting, which are often hardest to overcome. Care must be taken to recognize and overcome rationalizations to resume smoking (e.g., “just one cigarette won’t hurt”). Oral substitutes for cigarettes can be used, including gum, candy, carrot sticks, or sunflower seeds; exercise and deep breathing may also help alleviate withdrawal symptoms. Small self-rewards for milestones achieved (e.g., one week, one month) can help stay motivated to quit. To prevent relapses, reasons for quitting should be reviewed periodically, emphasizing benefits already achieved and those still to come.

Weight Loss

According to the Weight-control Information Network at the National Institutes of Health, there are two main categories of weight-loss programs: nonclinical and clinical.22 The former may be self-administered or performed with assistance from a weight-loss clinic, counselor, support group, book, or website. Nonclinical weight-loss programs should use educational materials written or reviewed by a physician or dietitian that address both healthy eating and exercise; programs neglecting the exercise component should be avoided (Figure 5-6). Although many commercial programs may promote proprietary foods, supplements, or products, these may be costly and will not teach participants about appropriate food selection to maintain long-term weight loss. Programs promoting specific formulas or foods for easy weight loss may offer short-term weight loss because of calorie restriction but should be avoided because they may not provide essential nutrients, do not teach healthy eating habits, and are not sustainable. Clinical weight-loss programs are administered by licensed health care providers including physicians, nurses, dietitians, or psychologists in a clinic or hospital setting. These programs may include nutrition education, physical activity, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), prescription weight loss drugs, or gastrointestinal surgery, depending on the desired weight-loss and health status.

Theory

Mechanisms of Action

Physical Activity

In general, exercises are used to strengthen muscles, increase soft tissue stability, restore range of movement, improve cardiovascular conditioning, increase proprioception, and reduce fear of movement. Engaging in physical activity through exercise programs is theorized to improve CLBP through multiple mechanisms, including improved conditioning and confidence for daily activities, release of endorphins, improved social interaction, reduced fear avoidance, and decreased generalized anxiety.23–27 The warmth of the water in hydrotherapy has also been purported to reduce muscle pain.28

Disc metabolism may also be enhanced through repetitive exercise involving the spine’s full active range of motion. Given that the absence of physical activity is known to reduce a healthy metabolism, it appears reasonable to believe that introducing exercise, such as lumbar stabilization exercise, may reverse such findings.29 The association between biochemical abnormalities in the lumbar discs and CLBP has previously been documented.30 Enhanced disc metabolism could improve repair and enhance reuptake of inflammatory and nociceptive mediators that may have migrated to an area of injury.

Smoking Cessation

Smoking cessation is thought to improve CLBP by decreasing exposure to the potentially harmful effects of smoking related to the lumbar spine. For example, it has been postulated that repeated microtrauma to the intervertebral discs from chronic coughing associated with long-term smoking can gradually lead to disc injury or herniation. Smoking is also thought to reduce blood flow to the discs, which already have a poor supply, as well as to the vertebral bodies.31 These effects could eventually lead to accelerated or early degeneration from insufficient healing capacity and decreased bone mineral density. The time required to fully or partially reverse these effects and observe clinical improvement of CLBP after smoking cessation is currently unknown.

Weight Loss

Weight loss is thought to improve CLBP by decreasing exposure to the potentially harmful effects of obesity related to the lumbar spine (e.g., additional weight on load-bearing spinal elements and altered biomechanics leading to excessive wear and early degeneration).17,32 It may also contribute to the improvement of CLBP by facilitating participation in general or back-specific exercises that may not be possible if a patient is overweight or obese. The time required to fully or partially reverse these effects and observe clinical improvements in CLBP after weight loss is currently unknown.

Indication

Physical activity is indicated for all patients with CLBP. Smoking cessation is indicated for all patients with CLBP who are smokers. Weight loss is indicated for all patients with CLBP who have a body mass index greater than 30, high-risk waist circumference, and two or more risk factors related to obesity.33 The included studies did not identify any factors related to the ideal patient for these interventions.23,34–39 However, all studies noted issues related to motivation, which needs to be taken into consideration when recommending patient-driven lifestyle modifications. Prochaska and DiClemente40 outlined five steps required to modify a person’s lifestyle: (1) precontemplation, (2) contemplation, (3) determination, (4) action, and (5) maintenance. Specifically in regard to health issues, persistent lifestyle changes have generally been initiated when patients connect their lifestyle risk factor to the disease at hand (contemplation stage). Often these require a major disease event such as a heart attack. In the case of CLBP, the primary health care provider may be critical in helping patients establish this link as the first step toward motivating them toward change.

Assessment

Before receiving physical activity, smoking cessation, or weight loss counseling, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating these interventions for CLBP. Certain questionnaires may be helpful to document the frequency of current physical activity, smoking, or caloric intake to establish a benchmark against which future outcomes can be compared.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Physical Activity

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found limited evidence that aerobic exercise was more effective than back school with respect to improvements in pain and function.41 This CPG also found strong evidence that advice to remain active, when combined with brief education, is as effective as usual physical therapy or aerobic exercise with respect to improvements in function.41

The CPG from Italy in 2007 strongly recommended low impact aerobic exercise for the management of CLBP.42

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found moderate-quality evidence to support the efficacy of aquatic therapy for the management of CLBP.43 This CPG also recommended advice to remain active.43

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 concluded that advice to remain active is likely to be beneficial.44

Weight Loss

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 5-1.

TABLE 5-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Physical Activity, Smoking Cessation, and Weight Loss for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion* |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | ||

| 41 | Europe | Limited evidence that aerobic exercise is more effective than back school Strong evidence that advice to remain active plus brief education is as effective as usual physical therapy or aerobic exercise |

| 42 | Italy | Recommended low-impact aerobic exercise |

| 43 | Belgium | Moderate-quality evidence to support efficacy of aquatic therapy Recommended advice to remain active |

| 44 | United Kingdom | Advice to remain active is likely to be beneficial |

* No CPGs made specific recommendations about smoking cessation or weight loss as interventions for chronic low back pain.

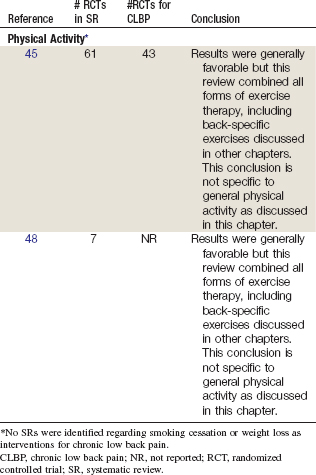

Systematic Reviews

Physical Activity

Cochrane Collaboration.

An SR was conducted in 2004 by the Cochrane Collaboration on all forms of exercise therapy for acute, subacute, and chronic LBP.45 A total of 61 RCTs were identified, including 43 RCTs related to CLBP. Although results were generally favorable, this review combined all forms of exercise therapy, including stabilization, strengthening, stretching, McKenzie, aerobic, and others. As such, these conclusions are not specific to general physical activity as discussed in this chapter. This review identified three RCTs (five reports) that may be related to general physical activity for CLBP, which are discussed below.23,35,38,46,47

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians.

An SR was conducted in 2007 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline Committee on nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic LBP.48 That review identified seven SRs related to all forms of exercise and LBP, including the Cochrane Collaboration review mentioned previously.45 Although results were generally favorable, this review combined all forms of exercise therapy, including stabilization, strengthening, stretching, McKenzie, aerobic, and others. As such, these conclusions are not specific to general physical activity as discussed in this chapter. This review did not identify any new RCTs.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Five RCTs and seven reports related to those studies were identified.23,35,36,38,46,47,49 Their methods are summarized in Table 5-3. Their results are briefly described here and are summarized in Figures 5-7 and 5-8.