Key Clinical Questions

Introduction

Peripheral arterial diseases (PAD) refer to arterial pathologies that affect the vasculature outside the heart and likely affect at least 8 million people in the U.S. The prevalence of disease depends on the methodology used to define PAD. Intermittent claudication (IC) can be defined as an exertional pain, soreness, or fatigue involving a group of muscles that causes the patient to stop during walking and usually resolves within five minutes of rest. The symptoms do not cease during exertion and do not begin at rest. The prevalence of IC varies from 1% to 5% of the U.S. population. Studies using the ankle-brachial index (ABI) to screen for PAD describe a much higher prevalence of PAD than those relying on symptoms of IC, with PAD measured by an abnormal ABI affecting as many as 12% of people age 65 years or older compared to only 2% of participants in one survey with classic symptoms of IC.

A 64-year-old woman developed “sore legs” during walking, worse on her right side. At first she attributed the discomfort to her “arthritic hip” but over the last six months she noticed that she can hardly walk to the end of her apartment corridor and walking up inclines is particularly difficult. Stopping to rest relieves the discomfort, and she has had no pain during sitting or while sleeping. Her past medical history includes a first myocardial infarction (MI) at 56 years of age, hypertension, Type II diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. She has a past history of smoking. Analysis This patient has classic symptoms of IC. A complete physical examination including a vascular examination should be performed. She does not have symptoms consistent with critical limb ischemia or acute limb ischemia, which would require either referral to a vascular specialist or admission for emergency evaluation and limb salvage. Diagnostic workup starts with a rest ABI +/– pulse volume recordings and/– segmental limb pressure examination. For secondary prevention, she should be educated about symptoms of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease and receive the same secondary prevention as patients with coronary artery disease. Her doctor should emphasize the importance of not resuming smoking. She should be prescribed aspirin or clopidogrel taking into consideration patient specific factors such as comorbidity, cost, and tolerability. The target LDL is the same as for cardiovascular disease, the target LDL is < 100 mg/dL, and < 70 mg/dl in the highest risk patients. Because aggressive BP management reduces cardiovascular events in the highest risk patients (including those with diabetes), her target BP should be < 120/80 mm Hg starting with an ACE inhibitor. Beta-blockers are not contraindicated in patients with PAD, and she should receive a beta-blocker given her prior MI. Resistant hypertension should be evaluated because patients with PAD may have atherosclerosis elsewhere, including the renal arteries. Diabetic patients with PAD are especially likely to develop nonhealing ulcers and require amputation. The patient should receive instructions about foot care and examine her feet daily. Glycemic control should be measured to optimize her Hg AIC. Statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors have been associated with improved survival in patients with PAD. Treatment Ideally, she should participate in a supervised exercise rehabilitation program that may improve her pain-free walking distance by up to 180% of baseline. In conjunction with exercise, cilostazol and pentoxifylline are approved pharmacology treatments by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Cilostazol has been shown to improve symptoms and increase walking distance and would be the first choice unless the patient has a reduced ejection fraction or has major risk of significant bleeding. |

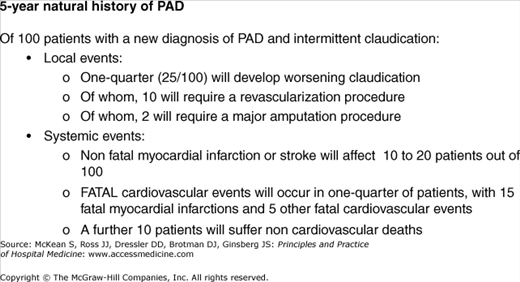

The risk of developing PAD increases with age, with a reported prevalence of disease in the U.S. population of between 15–20% in the over-70 age group, compared with 3–10% in the general population. Men are more commonly affected than women, although with the greater longevity of women, increasing numbers of women are surviving to develop this problem. Chronic lower limb ischemia can be a significant clinical problem for patients due to limitation of mobility and impaired exercise tolerance, poor wound healing and potential ulceration, and ultimately the risk of critical limb ischemia with gangrene and amputation. However, this traditional schema of the natural history of PAD does not describe the most common morbidity risk for patients with PAD: death or disability from systemic atherosclerotic disease. PAD is an ominous risk marker for atherosclerotic disease elsewhere, and the major adverse cardiovascular event rate (myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and vascular death) in PAD patients is 5–7% per year, with a five-year probability of a major nonfatal or fatal cardiovascular complication of 30%35%. Figure 263-1 shows the five-year risks of both limb-related (“local”) and systemic events in a patient with PAD, from a 1991 report.

Association with coronary artery disease

|

The value of identifying PAD in our patients goes beyond institution of appropriate management of the PAD itself. It should also encompass a holistic cardiovascular risk review, with emphasis on identifying and treating the modifiable atherosclerosis risk factors, including preventive pharmacological management as appropriate. Patients with PAD have substantial functional decline compared to patients without PAD. This chapter will primarily focus on atherosclerotic conditions of the lower limb arteries. We will examine the practical aspects of screening for PAD, how to make a diagnosis of PAD, and consider the management options. Refer to other chapters for carotid and abdominal atherosclerotic pathologies.

PAD arises when an obstruction (typically an atherosclerotic plaque within the arterial lumen) limits blood flow to the lower limbs. A hemodynamically significant stenosis decreases both blood flow and blood pressure distal to the stenosis, and this pressure drop is present regardless of whether the patient is resting or exercising. The patient’s distal arterioles dilate to ameliorate the reduction in flow distal to the stenosis, so that the patient may be asymptomatic at rest. However, when the patient exercises, the peripheral muscles require an increase in arterial blood flow, but the arterial flow may be insufficient due to the stenosis, thereby causing symptoms.

Atherosclerotic disease most commonly affects major arterial bifurcations in areas of acute angulation and turbulent blood flow, such as the distal superficial femoral artery in the Hunter canal, the common femoral artery extending into the superficial femoral artery, and the distal aorta and aortic bifurcation. PAD may be initially asymptomatic, but can progress to a complicated spectrum of symptoms and signs, with gangrene and limb loss as the most serious limb-related adverse outcome. Primarily an atherosclerotic condition, PAD has risk factors similar to those for other atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases; notably, advanced age, tobacco use, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Smoking is also implicated as the primary insult in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger disease). This condition typically affects men in their 30s or 40s, and they present with a history of tobacco smoking and a rapidly progressive vasculopathy with stenoses and occlusions of multiple arteries. Other risk factors include race and ethnicity, elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, leukocytes, and interleukin-6, impaired renal function, hypercoagulable states such as abnormal levels of D-dimer, homocysteine, and lipoprotein(as), other genetic factors, and abnormal waist-to-hip ratio. In addition, the presence of atherosclerosis in the coronary tree is associated with increased PAD risk. Obese patients with PAD who have elevated levels of inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, serum amyloid A, and D-dimer) and do not exercise are more likely to suffer a significant decline in physical function. Less commonly, PAD may be associated with other systemic conditions such as collagen vascular diseases and the vasculitides. A more complete list of associations is seen in Table 263-1.

| Disease Group | Specific Conditions |

|---|---|

| Atherosclerosis | Associated with CVD risk factors; also Buerger disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) |

| Degenerative diseases | Marfan syndrome, Ehrler Danlos syndrome, cystic medial necrosis, neurofibromatosis |

| Vasculitides | Small vessel vasculitides, such as those associated with systemic connective tissue or automimmune diseases, eg, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis |

| Medium vessel vasculitides, such as giant cell arteritis, polyareteritis nodosa, Wegener syndrome, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Kawasaki disease | |

| Large vessel vasculitides, such as Takayasu disease, Behcet syndrome, relapsing polychondritis, vasculitis associated with arthropathies | |

| Thrombosis and thromboembolism | Thrombosis in situ (eg, due to disposing factors: thrombophilia, trauma, dissection) or thromoboembolism due to arterial emboli |

| Dysplastic diseases | Fibromuscular dysplasia |

Localized PAD can also be due to such diverse causes as an aneurysm, trauma, congenital causes, and entrapment syndrome. Intermittent claudication without arterial obstruction may be seen in patients with severe anemia, pheochromocytoma, and amyloidosis.

Presentation

As already described, PAD as diagnosed by ABI measurement can be asymptomatic. Especially in the elderly, other comorbidities such as severe heart or lung disease may limit their physical activity and delay the presentation of PAD. Furthermore, some patients severely limit their walking to avoid exertional leg symptoms, and present therefore with progressive functional decline rather than typical IC. The presence of atherosclerotic risk factors should alert the clinician to the possibility of PAD and to proceed with an examination looking for evidence of PAD.

Symptoms of IC occur distally to the obstruction at times of higher oxygen and blood flow demand. Classically, patients describe exercising to their usual limit, at which time they experience calf pain. Patients cannot “walk through” the pain of IC, and ultimately have to rest for up to five minutes before resuming exercising. Symptoms of intermittent claudication do not always manifest as “pain.” However, ischemic symptoms whether pain, cramping, aching, or fatigue should always arise in a functional muscle group, be reproducibly precipitated by exercise, and relieved by rest. The clinician should note both the claudication distance (how far the patient can walk before the onset of any pain) and the absolute claudication distance (the distance at which the pain becomes so severe as to necessitate stopping).

Symptoms may suggest the location of the obstruction at one of three levels: aortoiliac, femoropopliteal, and tibial artery (crural, below-the-knee, or infrageniculate) segments.

Clinical clues to origin of ischemic symptoms Arterial disease in the lower extremity Aortoiliac disease

Femoropopliteal disease

Tibioperoneal disease

|

Thigh or buttock pain on exertion, sometimes associated with impotence, should alert the clinician to the possibility of Leriche syndrome due to internal iliac arterial disease. The initial presentation and course of PAD in diabetic patients typically differs from PAD in patients with atherosclerosis.

Both smoking and diabetes accelerate the course of PAD with a higher projected five-year mortality and likelihood of requiring surgical intervention.

Patients with IC are more likely to have single-level disease, and patients with rest pain or skin ulceration are more likely to have multilevel obstruction. Because patients with PAD may have involvement of multiple arterial segments with symptoms throughout the leg, the vascular laboratory can be helpful in localizing the hemodynamically significant stenosis or stenoses.

Intermittent claudication (IC) Intermittent claudication

Pseudo-claudication (from spinal stenosis)

Venous claudication (from venous hypertension in obstructed veins)

|

Comorbidities such as knee or hip arthritis, spinal disc disease, and spinal stenosis are more prevalent in patients who describe limb pain but who do not have classic symptoms of IC. Osteoarthritis of the hip or spinal canal narrowing can also cause hip and buttock pain and may coexist with PAD. Similarly, pain from venous disease, nerve root compression, or spinal cord stenosis can cause calf pain.

The history and physical examination should be able to differentiate other causes of exercise-induced lower extremity pain such as the chronic compartment syndrome, peripheral nerve pain, and hip and knee osteoarthritis.

In more severe cases of PAD, critical limb ischemia may occur. Critical ischemia refers to chronic and severe obstruction of blood flow to the point that basal metabolic needs of the limb are not met. Patients first describe “rest pain,” in which they experience troublesome ischemic pain at rest or at night when lying down. Unlike neuropathic pain, it may be relieved by placing the foot in a dependent position. Patients may describe hanging their affected foot out of bed at night in the search for some relief of their pain. The pain will likely be diffuse foot pain that may extend distally to the metatarsals. It may be accompanied by painful paresthesias and/or aching. Patients may have painful ischemic skin ulcers that typically form after minor trauma (shins, toes), or even frank gangrene. Arterial ulcers are pale to black in color, punctate, and well-circumscribed, unlike venous ulcers, which have thickened, brawny, hyperpigmented skin typically located in the region above the medial malleolus. Arterial ulcers should not be confused with diabetic ulcers. The latter typically arise over weight-bearing areas, have surrounding hypertrophic callus formation, and likely have associated infection. Unlike IC, patients with critical limb ischemia require either percutaneous or open surgical intervention to improve blood flow and to avoid major amputation.

Diabetic patients Compared to nondiabetics, diabetic patients have

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree