Chapter 5 Perioperative Safe Medication Use

A Focused Review

In 1859 Florence Nightingale (1970) wrote in Notes on Nursing, “It may seem a strange principle to enunciate as the first requirement in a hospital that it should do the sick no harm.” This tenet had already been the basis for physicians, given the centuries-old standard of first and foremost, do no harm. Yet there remains public concern among patients who enter the health care system, and rightly so. Within the past decade the Institute of Medicine (IOM) brought renewed attention to this hallowed tenet through its seminal report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, when it asserted that up to 98,000 deaths occurred annually as the result of medical errors (Kohn et al, 2000). Citing data that health care institutions had caused harm or death (Kohn et al, 2000), the IOM went further in describing the health care system of the twenty-first century. In the newer model of patient safety through the avoidance of iatrogenic injury, safety would be the new and minimally accepted standard of care (IOM, 2004). Because of these reports, patient safety has become a mantra for all within health care.

Safe medication use has always been just one important aspect of patient safety. Violations of safe medication principles, policies, and processes and the resultant medication errors now serve as the markers of evidence for warranted concern. Such markers gain worldwide attention through headline stories that reflect personal tragedies of countless victims. Although the full extent of medication errors is unknown, there are indicators that such system failures are pervasive, which reflects poorly on the world’s most advanced health care system. The IOM claimed that up to 7000 deaths were directly attributable to medication errors (Kohn et al, 2000). Other investigators have estimated that errors can affect 20% of all routinely administered medication doses (Barker et al, 2002). Researchers from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration investigated the agency’s medication error database, the Adverse Event Reporting System, and found that 10% of the reported errors over a 6-year period resulted in death (Phillips et al, 2001). Still other investigators have claimed that up to 9% of all hospital admissions result from medication errors (Winterstein et al, 2002). In fact, as of December 31, 2007, medication errors were the fourth leading reported sentinel event in hospitals across the United States according to the sentinel event statistics reported by The Joint Commission. Given that all medication errors are preventable (National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, 2008), it is no wonder that safe medication use became a focal point in numerous initiatives aimed at reducing the burden of iatrogenic injuries.

Since the release of To Err Is Human, great strides have been made to better understand the complexity of the health care system and how that complexity affects patient safety (Rudman et al, 2002). In turn, this understanding has guided the development of or revisions to professional guidelines (Association of periOperative Registered Nurses [AORN], 2008), national and international campaign initiatives focused on safety (World Health Organization [WHO], 2006), and state and federal laws (Shojania et al, 2001). Many of these activities have influenced safe medication practices to help move the health care delivery system to one that ensures that patient safety is the standard of care (Leape, 2002).

NATIONALLY AND INTERNATIONALLY RECOGNIZED CONCEPTS ASSOCIATED WITH ERRORS

The Value of Medication Error Reporting

Event reporting systems can be powerful tools to build knowledge when the findings are used to improve systems and educate providers (Wachter, 2004). The intent behind such systems is to collate and analyze the risks associated with related activities to propose remedial and preventive actions (Leape, 2002). A reporting system includes multiple components: empiric and theoretic models, a variety of tools built from domain content, and analysis by domain experts (Nyssen et al, 2004).

Even before To Err Is Human was published, the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) had suggested significant patient safety initiatives drawn from the evidence of two national medication error reporting programs: the USP Institute for Safe Medication Practices Medication Errors Reporting Program and MEDMARX. The Medication Errors Reporting Program is a voluntary program open to all clinicians in all settings. This database, which is operated in cooperation with the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, collects information and provides data to regulatory agencies, professional organizations, and the pharmaceutical industry in an effort to educate about preventing future adverse drug events. MEDMARX, launched in 1998, is an Internet-accessible, anonymous medication error database used by hospitals and health systems and is available through an annual subscription service. MEDMARX provides subscribers with an opportunity to track adverse medication events within the facility, review errors reported by other facilities in the database, conduct comparisons between facilities, and examine quality improvement initiatives that other facilities have implemented in response to medication errors (Hicks et al, 2004). Although the facilities that report to MEDMARX currently constitute less than 10% of all U.S. hospitals and health care systems, USP has amassed the largest repository of medication error data currently available in the world, with more than 1.25 million case reports from more than 770 facilities. It is important to note that the number of case reports represents only those that have been voluntarily reported to MEDMARX.

When discussing the concept of reporting, it is important to recognize that two aspects occur: (1) errors are reported, and (2) errors are not reported. Errors that are not reported can be further segmented into those intentionally not reported and those that are not detected. The Iceberg Model is an excellent representation of this phenomenon. Researchers studying the relationship between detected and reported errors have found wide variances between what is reported (the tip above the water) and what is undetected and remains unreported (the ice mass below the water) (Barker et al, 2002; Flynn et al, 2002; Shaw-Phillips, 2002). Furthermore, extending the analogy and comparing reporting with not reporting, the mass that remains “under water” represents lost opportunities to learn from mistakes that could be used to improve health care systems.

Leape (2002) identified seven characteristics of successful reporting systems based on published expert opinions: (1) nonpunitive (free of fear of retaliation), (2) confidential (deidentified patient, reporter, and institutional information), (3) independent (analysis is done by an organization without power to punish), (4) expert analysis (content experts), (5) timely (prompt), (6) responsive (dissemination of results), and (7) systems oriented (focused on changes in systems and processes rather than on individual performances). Applying these characteristics to perioperative conditions (including errors) yields richness within practice to advance the profession.

National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention

Before discussing medication errors, the common languages used to report, analyze, and discuss medication errors and the medication use process (MUP) must be understood. Our understanding today of medication errors can be attributed to several sources, including early work done by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP). Formed in July 1995 from 22 different constituent-based organizations, NCC MERP (2008) and its members cooperatively addressed the multidisciplinary causes of medication errors to promote safe medication use. NCC MERP (2008) produced the nation’s first comprehensive taxonomy for studying medication errors and established the nationally recognized definition of a medication error:

Medication Error Severity

NCC MERP also created the Index for Categorizing Medication Errors to determine the outcome or effect of the medication error on the patient. The index contained four major subscales: (1) potential for error (category A); (2) actual error that did not reach the patient (category B); (3) actual error that reached the patient but did not result in harm (category C or D); and (4) actual error that reached the patient and resulted in harm (category E, F, G, H, or I). The reliability of this scale (κ = 0.60) was established in 2007 by a group of researchers at the Ohio State University (Forrey et al, 2007).

Medication Use Process

The MUP is a systems approach that defines the typical manner in which medications move through an institution in terms of prescribing, dispensing, and administering to patients (Nadzam, 1998). According to USP, each step or point in the MUP is referred to as a node (Hicks et al, 2004). Each node represents domains of professional responsibilities, including the corresponding series of checks and balances and professional judgments that seek to ensure safe medication use. Table 5-1 lists the nodes of the MUP and the corresponding definitions.

TABLE 5-1 The Medication Use Process

| Node | Definition |

|---|---|

| Procuring | The formal action of how organizations obtain products |

| Prescribing | The action of a legitimate prescriber to issue a medication order |

| Transcribing | Anything that involves or is related to the act of transcribing an order by someone other than the prescriber for order processing |

| Dispensing | A phase that begins with a pharmacist’s assessment of a medication order and continues to the point of releasing the product for use by another health care professional |

| Administering | A phase in the MUP in which the drug product and the patient interface |

| Monitoring | The phase that involves evaluating the patient’s physical, emotional, or psychologic response to the medication and then recording such findings |

MUP, Medication use process.

From Hicks RW et al, editors: MEDMARX data report: a report on the relationship of drug names and medication errors in response to the Institute of Medicine’s call for action, Rockville, Md, 2008, Center for the Advancement of Patient Safety, US Pharmacopeia.

Nursing school curricula and nursing practice have historically drawn heavily on one safe medication practice known as the “five rights,” which was intended to ensure that the right patient received the right dose of the right drug at the right time and by the right route. Nurses have used this guiding practice extensively. Furthermore, it has served as the legal standard for safe practice, because satisfying each of the “rights” offered maximum protection against medication errors. However, this practice is not foolproof, given that the national medication error reporting program MEDMARX contains data suggesting that one-third of the reported medication errors that occurred between 2002 and 2006 took place during medication administration (Hicks et al, 2008).

The continued prevalence of medication errors during drug administration indicates that the practice of five rights alone is not adequate to keep patients safe from medication errors. The Illinois Court of Appeals found this when it rendered its decision that hospitals were responsible for the negligence of nurses performing physicians’ orders by giving medications that were clearly contraindicated for the patient (Medication Ordered Is Contraindicated, 2007). In this case there was an underlying “assumption” that there was correct execution of tasks in all of the preceding steps within the MUP that ultimately proved to be inaccurate. Directly resulting from this case, two additional rights (the right indication and the right documentation) have been added to the standard for using medications safely. Furthermore, this case set legal precedence that in effect raised the bar by indicating that the five rights should not be the sole “safety net” for medication administration. Rather, undertaking a review of all steps of the entire MUP before administering a medication should be required to protect the patient.

STATE OF THE SCIENCE IN PERIOPERATIVE SAFE MEDICATION USE

The OR is a unique environment. What occurs behind the pneumatic doors of the OR takes a special skill set that is not required within many other specialties in health care. Few researchers have focused on specific problems associated with safe medication use in the OR (Beyea et al, 2003). Rather, studies have investigated other important clinical topics such as instrument and sponge counts, new technologies, and fire safety. Therefore the literature offers very limited guidance for practitioners to improve safe medication use in the OR. Some of the earliest literature comes from researchers reporting findings collected through the Australian Incident Monitoring Study (Runciman et al, 1993) that support the conclusion that system failures contributed to human errors in the OR setting. In fact, most of the current knowledge about medication errors in the OR stems from studies led by anesthesiologists; thus national safety experts recognize anesthesiology as the founding discipline of patient safety.

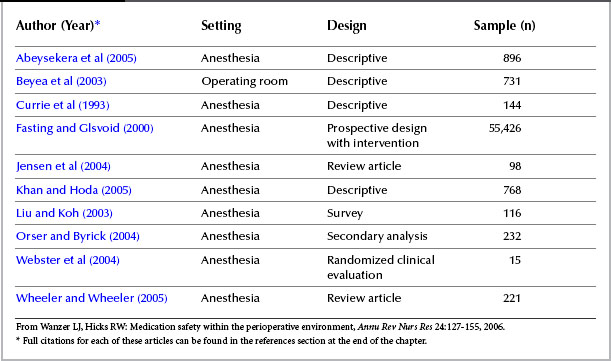

Wanzer and Hicks (2006), using the NCC MERP taxonomy, recently conducted a review of 10 articles that examined medication errors in the OR (Table 5-2). This focused review provided one look within the unique environment of the OR regarding medication safety and improving clinical outcomes. The investigators concluded that the science involving perioperative safe medication use was in its early stages. They supported this claim by drawing on systematic reviews of the literature, descriptive studies, and secondary analyses because there were few randomized clinical evaluations to provide evidence. Support for their conclusion included the inconsistency of the methods used to identify errors, variations in measuring patient outcomes, and lack of consensus about what constituted an error.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree