Chapter 8 Perioperative Patient Safety and Procedural Sedation

The concept of patient safety was brought to the forefront in 1999 when the Institute of Medicine published To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Kohn et al, 2000). The authors of the report focused on the impact of medical or health care errors occurring in patients and delineated patient safety as a priority for the health care community The report pointed out that error was the property of a system of care as opposed to individual health care providers and that those systems should provide well-designed processes of care that result in prevention, recognition, and early recovery from errors to ensure that patients remain safe and unharmed (Donaldson, 2008).

The use of sedation administered by nonanesthesia providers for procedures has increased exponentially over the past decade. The term procedural sedation is used interchangeably with moderate sedation. Procedural sedation is a term that is considered by many to be a more comprehensive description of the actual techniques applied. Procedural sedation “refers to the techniques of managing a patient’s pain and anxiety to facilitate appropriate medical care in a safe, effective, and humane fashion” (Brown, 2005). Procedural/moderate sedation is performed in the perioperative environment and in other nonsurgical environments such as the endoscopy suite, the cardiac catheterization laboratory, the radiology department, the labor and delivery suite, physician offices, emergency departments, and dental offices. This use of procedural or nurse-monitored sedation has partially been driven by economic factors, because some insurance companies are unwilling to pay anesthesia providers for monitored anesthesia care during many routine procedures, and by the need to move patients quickly through the procedural area—a more difficult process when scheduling anesthesia (Meltzer, 2003).

The safety of the patient is the primary concern for perioperative registered nurses (RNs) involved in administering sedation or monitoring the patient who has received procedural/moderate sedation (Odom-Forren, 2005). Procedural/moderate sedation is safe, but has potential adverse reactions such as hypoxemia, apnea, hypotension, airway obstruction, and cardiopulmonary arrest (Gross et al, 2002; Vargo, 2007). As a member of the Dartmouth Summit stated, “the side effects of the procedure can traumatize you; the side effects of the sedation can kill you” (Blike and Cravero, 2000). However, the RN alone cannot guarantee the safety of the patient. Patient safety is the responsibility of every person on the perioperative team and relies on an effective sedation delivery system to keep the patient from harm.

SEDATION ISSUES RELATING TO PATIENT SAFETY

Sedation on a Continuum

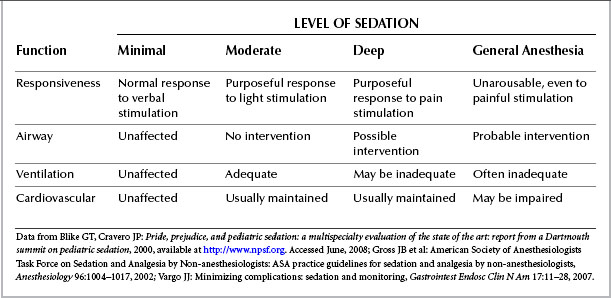

Sedation falls on a continuum from minimal sedation to deep sedation. Typically, nurse-monitored sedation falls under the definition of moderate sedation. Minimal sedation is used to decrease anxiety but should not affect the patient’s respiratory or cardiovascular functions; however, the patient is under the influence of the medication administered and should be treated as such. The patient receiving moderate sedation should be able to maintain respirations without significant cardiovascular changes. With this type of sedation the patient is able to respond to verbal or mild tactile stimulation. The risk for complications increases as the patient moves on the continuum from minimal to moderate sedation. The patient who is receiving moderate sedation has the potential to move into deep sedation and thus become at higher risk for complications. A patient receiving deep sedation should be able to respond to repeated or painful stimulation. The patient receiving deep sedation also is at an increased risk for respiratory compromise, although cardiovascular status is usually preserved. If the patient receiving sedation at any time becomes unresponsive, that patient is receiving general anesthesia with risk for respiratory compromise, cardiac compromise, or both (Blike and Cravero, 2000; Gross et al, 2002; The Joint Commission, 2008). The further the patient moves on the continuum, the greater the risk for the patient (Table 8-1).

Adverse Reactions

Respiratory depression is the most common adverse reaction to procedural sedation. One panel discussing the risks of sedation noted that sedation complications are related to underuse, overuse, or misuse. Underuse complications cause patients to suffer unnecessary pain and stress, whereas overuse complications can result in respiratory depression or apnea. Misuse complications involve errors in drug administration (e.g., administering sufentanil instead of the ordered medication fentanyl) (Blike and Cravero, 2000).

Cote et al (2000) studied adverse sedation events in pediatric patients. In this critical incident analysis, there were 60 events that resulted in death or permanent central nervous system injury. Respiratory depression was the first event in 80% of the patients. Poor outcome was associated with inadequate resuscitation, inadequate monitoring, inadequate initial evaluation, and inadequate recovery phase.

In a report of adverse events during pediatric sedation and anesthesia outside the operating room, 26 institutions submitted data on 30,037 patients for a period of 17 months. Serious adverse events were rare, with no deaths and cardiopulmonary resuscitation being required only once. Less serious events occurred, such as oxygen desaturation below 90% for more than 30 seconds (157 times per 10,000 sedations), unexpected apnea (24 times per 10,000 sedations), and vomiting (47.2 per 10,000 sedations). Even with a low incidence of serious adverse reactions to pediatric sedation, the number of events that had potential to harm was significant, occurring once in every 89 sedations (Cravero et al, 2006). Because events with the potential to compromise patient safety are so common, it is imperative that personnel involved in sedation be competent to manage an airway obstruction, emesis, hypoventilation, and apnea (Hertzog and Havidich, 2007).

Adverse reactions to sedation are an international problem. From a questionnaire sent to nonanesthesia providers to assess sedation practices in Ireland, Fanning (2008) found that 22% of respondents reported events including respiratory depression, hypoxia, loss of consciousness, prolonged sedation, and nausea and vomiting. Two events required the presence of an anesthesia provider (Fanning, 2008). Sedation was the cause of most complications that occurred in a study conducted in Germany to determine complications in outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopy patients (Sieg et al, 2001).

In 121 monitored anesthesia care cases pulled from the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Closed Claims database (1990–2002), the severity of complications was similar to that found with general anesthesia (Bhananker et al, 2006). Twenty-one percent of the claims were caused by respiratory depression secondary to the sedative medications. These events were associated with older age (70 years or older), ASA physical status III and IV, and obesity. Propofol or benzodiazepines used alone were associated with oversedation in 9% of the patients. Propofol with the use of another medication was responsible for 50% of the patients diagnosed with oversedation (Bhananker et al, 2006). This information about patients receiving monitored anesthesia care can be assumed to also apply to patients receiving sedation and analgesia from nonanesthesia providers such as the perioperative RN.

The low percentages of serious complications such as aspiration or hypoxia with resulting neurologic impairment or death require that larger studies be undertaken than have been conducted to date. Surrogate markers are typically used in studies to determine the potential for serious adverse reactions. A surrogate marker commonly used in sedation studies is respiratory depression, with an operational definition for the study such as apnea longer than 30 seconds or oxygen saturation falling below 90%. The occurrence of cardiopulmonary complications is used as a surrogate marker of the risk for occurrence of a significant adverse event (Vargo, 2007). Studies conducted with surrogate markers are able to use lower numbers of patients but have unclear clinical significance (Miner and Krauss, 2007; Vargo, 2007). In summary, although the severe complication rates are low for procedural sedation, failure to recognize or immediately treat these patients can lead to morbidity or even death. Of great importance are patient risk assessment and rescue capabilities (Cravero et al, 2006).

Patient Risk Factors

Preprocedure assessment and identification of high-risk patients is the key to the prevention or successful management of sedation-related events (Hooper, 2005b). Patients at high risk for complications should be evaluated during the preprocedure assessment for appropriateness of nurse-monitored sedation (Table 8-2). Patients at risk for a difficult airway are important to identify because respiratory complications are commonly associated with sedation. Risk factors associated with a difficult airway include a history of problems with anesthesia or sedation, advanced rheumatoid arthritis, chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., trisomy 21), and stridor, snoring, or sleep apnea (Gross et al, 2002; ASA, 2008).

TABLE 8-2 Patients at High Risk for Sedation-Related Complications

| Risk Factor | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Presence of airway abnormalities | |

| ASA classification status of III or greater | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |

| Obesity | |

| Coronary artery disease | |

| Chronic renal failure | |

| Drug addiction | |

| Extremes of age (pediatric and older adult patients) | Administer individual and incremental dosing. |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Data from American Society of Anesthesiologists: Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway, available at http://www.asahq.org/publicationsAndServices/Difficult%20Airway.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2008; Gross JB et al: American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-anesthesiologists: ASA practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists, Anesthesiology 96:1004–1017, 2002; Hooper VD: Management of complications. In Odom-Forren J, Watson D, editors: Practical guide to moderate sedation/analgesia, ed 2, St. Louis, 2005, Mosby; Martin ML, Lennox PH: Sedation and analgesia in the interventional radiology department, J Vasc Interv Radiol 14:1119–1128, 2003.

SEDATION PRACTICE ISSUES

The role of the RN administering deep sedation is more controversial. Currently no consensus exists among state Boards of Nursing or governing bodies regarding the role of the RN administering deep sedation. Many times when asked to provide deep sedation, the RN is required to administer a drug labeled as an anesthetic agent (e.g., propofol). (See section later in chapter on propofol administration.) In other cases, deep sedation requires a higher dosage of a typical sedative than the dosage required for moderate sedation. In both cases, the safety of the patient should be the first and most important concern. It is prudent for the RN who is requested to administer deep sedation to know the position of the specific state BON or governing body in the specific state where the practice will occur. If deep sedation is considered to be an acceptable practice in the state, then the individual health care facility should have an educational process in place with a method for determining competency of the RN that is required to care for the patient receiving sedation (Odom-Forren, 2005; Odom-Forren and Watson, 2005). Guidelines are available that differentiate care for the patient undergoing moderate sedation from the one undergoing deep sedation. Any policy outlined by a health care facility for deep sedation should include parameters set by the state BON or governing body and available guidelines, such as those published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (Gross et al, 2002). It is significant to note that the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) (2009) offers “Recommended Practices for Managing the Patient Receiving Moderate Sedation/Analgesia,” which is an excellent resource for the perioperative RN. The AORN recommended practices state that certain patients are not appropriate candidates for monitoring by the perioperative nurse, and in those situations it is more appropriate to have the monitored anesthesia care provided by an anesthesia provider (AORN, 2009).

Use of Propofol for Sedation

The use of propofol by nonanesthesia providers in sedation and analgesia has been fraught with controversy (Odom-Forren, 2005; Odom-Forren and Watson, 2005). The advantages of propofol (over benzodiazepines) include less nausea, more-rapid onset, and shorter duration of action, facilitating faster recovery and discharge (Patterson, 2004; Kremer, 2005; Odom-Forren, 2005; Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 2008). Zed et al (2007) evaluated the efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction with the use of propofol for procedural sedation for 113 patients in the emergency department. One patient experienced vomiting, 0 experienced apnea, 9 experienced hypotension, and 7 felt pain on injection. All patients and most physicians were satisfied with the use of propofol. The investigators concluded that as part of a standardized protocol, propofol appears to be safe and effective, with high patient and physician satisfaction (Zed et al, 2007). In three other studies that were conducted using nurse-administered propofol sedation (NAPS) with a total of 11,000 patients undergoing gastrointestinal procedures, the investigators found no major complications (Rex et al, 2002; Heuss et al, 2003; Walker et al, 2003). In an article from a university setting where NAPS is used on a regular basis, Overly and Rex (2004) discussed the use of NAPS as cost-effective and satisfying for physicians and nurses. In one study of 33,743 endoscopic procedures using NAPS (Rex et al, 2005), no cases of endotracheal intubation, death, neurologic sequelae, or other permanent injury occurred. Temporary bag-mask ventilation was required by 49 patients. The three centers with a training program conducted by anesthesiologists had a center-specific rate of complications from 9 per 10,000 to 19 per 10,000 (Rex et al, 2005).

Opponents of the use of NAPS point out that the good outcomes of these studies conceal the risks with the use of propofol. Those risks include the tendency to attain deep sedation or even general anesthesia on the sedation continuum, with the resulting problems of airway obstruction and apnea. No reversal agent for propofol is available when these events occur (Gross et al, 2002). Anesthesia providers are quick to note that the absence of morbidity or mortality in a smaller sample of patients should be moderated by the fact that morbidity and mortality for healthy patients undergoing anesthesia is only 1 in 300,000 (Philip, 2008). Vargo (2007), who believes that the safety and efficacy of propofol for use in sedation has been established, goes on to state that the current data in randomized controlled trials do not sufficiently answer the question of its safety compared with standard sedation and analgesia.

The jury is out on the widespread use of propofol for sedation until regulatory agencies, third-party payers, and professional societies come to the same conclusion about propofol’s safety. One concern related to nurse-monitored sedation includes propofol’s strict product labeling as an anesthetic agent to be used by persons trained in the administration of general anesthesia (Meltzer, 2003). State Boards of Nursing have varying positions regarding the use of propofol administered by nurses, with some boards (e.g., Indiana) stating that it is within the scope of nursing practice for a competent and educated nurse to administer propofol for sedation, and others (e.g., Florida) stating that is not within the scope of practice for a registered nurse to administer propofol (Odom-Forren and Watson, 2005). In 2005 the AORN board of directors endorsed the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists (AANA) and ASA joint statement indicating that only health care professionals trained in general anesthesia should administer propofol (AORN, 2009; ASA, 2009).

In December 2008 a new drug, fospropofol sodium, was approved for monitored anesthesia care sedation. Fospropofol is a water-soluble prodrug of propofol and is used by determining a weight-based bolus (Vargo, 2007). While undergoing studies, it was unknown whether the increased plasma half-life would mean prolonged recovery, but it was hoped that the drug would be able to maintain a patient at the level of moderate sedation. For short-duration procedures, it is possible that patients may require only a single dose (American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2008). However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) used the same wording with fospropofol as with propofol, requiring use only by persons trained in the administration of general anesthesia, and further states that all patients should be continuously monitored by persons not involved in the conduct of the procedure (FDA, 2009).

Guidelines for the ASA and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) have specific criteria for monitoring patients who are under deep sedation, including a committed, qualified practitioner administering the sedation and the evaluation of ventilatory function with consideration of capnography (Gross et al, 2002; ASGE, 2008). The ASA and the ASGE have determined components of a training program for any health care facility that uses NAPS with resultant deep sedation. The ASGE includes an initial phase of training, including didactic material that discusses the sedative agents to be used, contraindications for specific agents, and certification in advanced cardiac life support or the equivalent. Other components of the ASGE program include a written test on didactic material, airway assessment, observation, and administration under supervision (Rex, 2006). Contraindications to propofol administration by nonanesthesia providers at Indiana University, where NAPS is widespread, include increased aspiration risk (e.g., acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, achalasia, delayed gastric emptying, bowel obstruction); difficult airways (e.g., sleep apnea requiring continuous positive airway pressure, marked obesity, abnormal airway assessment); extreme comorbidities; and allergy to propofol (or to eggs or soybeans) (Rex, 2006). Although the ASA is opposed to NAPS, the ASA has developed criteria that address the safe use of propofol when used by nonanesthesiologists (Box 8-1).