Introduction

Pain is the most common symptom of disease. It is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or potential tissue damage. There are sound medical and legal reasons to treat pain aggressively in hospitalized patients. The Joint Commission, which certifies all health care institutions in the United States, mandates that all patients have the right to adequate pain assessment and management (Table 49-1).

|

In the inpatient setting, patients may be more concerned about pain relief than the outcome of their underlying illness. Poor pain control has adverse physiologic consequences that lead to worse outcomes (Table 49-2).

| Cardiovascular | Tachycardia, hypertension, increased cardiac workload |

| Pulmonary | Hypoxia, hypercarbia, atelectasis, decreased cough |

| Gastrointestinal | Decreased gastric emptying, nausea/vomiting, ileus |

| Renal | Urinary retention |

| Endocrine | Increased adrenergic activity, catabolic state, sodium/water retention |

| Immunologic | Impairment, slowed wound healing |

| Musculoskeletal | Splinting, contractures, decreased mobility (deep vein thrombosis) |

| Hematological | Increased coagulability |

| Neurological | Anxiety, fear, anger, fatigue, delirium |

|

Pathophysiology: Nociceptive and Anti-Nociceptive Pathways

Nociception, the perception of noxious stimuli, is a preconscious neural activity that is normally necessary, but not sufficient, for pain. It is more accurate to refer to nociceptive pathways, rather than pain pathways. The peripheral nerve fibers acting as nociceptors are lightly myelinated A-delta and unmyelinated C fibers, which are triggered or sensitized (peripheral sensitization) by several substances, including adenosine triphosphate (ATP), prostanoids, bradykinin, serotonin, histamine, and hydrogen ions. Heat, pressure, or nerve damage also results in activation.

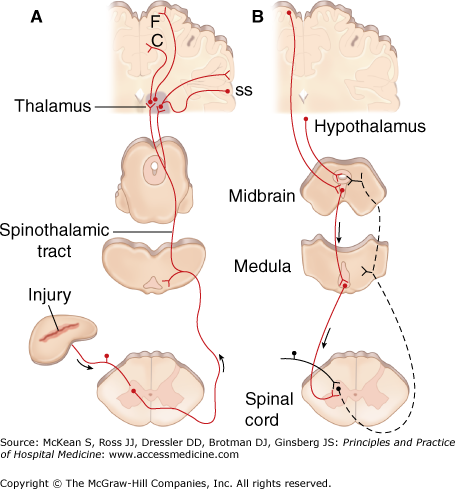

The primary nociceptors synapse in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Figure 49-1), where the excitatory amino acids glutamate and aspartate and peptides such as substance P serve as neurotransmitters. Noxious impulses ascend in the lateral spinothalamic tract to the medial and lateral thalamus and spread to sensory regions of the cerebral cortex. Parts of the limbic system are also activated; presumably, this is where nociception is associated with emotion and arousal and becomes pain.

Figure 49-1

Nociception transmission and pain modulatory pathways. A, Transmission system for nociceptive messages. Noxious stimuli activate the sensitive peripheral ending of the primary afferent nociceptor by the process of transduction. The message is then transmitted over the peripheral nerve to the spinal cord, where it synapses with cells of origin of the major ascending pain pathway, the spinothalamic tract. The message is relayed in the thalamus to the anterior cingulate (C), frontal insular (F), and somatosensory cortex (SS). B, Pain-modulation network. Inputs from frontal cortex and hypothalamus activate cells in the midbrain that control spinal pain-transmission cells via cells in the medulla. (Reproduced with permission from Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008, Fig. 12-4.)

The nociceptive system has built-in positive and negative feedback loops. Prolonged firing of nociceptors enhances synaptic transmission to dorsal horn neurons. This process of central sensitization involves glutamine and a host of other mediators. Central sensitization is an adaptive response that prevents further injury during a vulnerable period of tissue healing. This heightened sensitivity generally returns to baseline over time. However, if central sensitization is prolonged beyond the healing phase, chronic pain may result.

Substance P-mediated nociception is antagonized by local production of endogenous opiates, such as enkephalins and endorphins, in the dorsal horn and the brain stem. Binding of narcotics to opiate receptors in these locations may account for the analgesic effects of these drugs. As well, powerful top-down, endogenous mechanisms of pain modulation originate in the cortex and travel through brain stem and midbrain structures en route to the spinal cord. These descending pain control pathways are mediated by noradrenergic and serotonergic transmission, as well as endogenous opiates.

Characterizing Pain Intensity

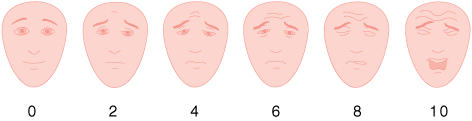

The most commonly used measures of pain intensity in the acute setting are single-dimension scales (Table 49-3). A numerical rating scale has the numbers 0 to 10 spaced evenly across a page, where 0 is “no pain at all” and 10 is “the worst pain imaginable.” Patients are instructed to circle the number that represents the amount of pain they are currently experiencing. A common variation is the verbal numeric scale, where patients are asked to verbally state a number between 0 and 10 to correspond to their present pain intensity. Some people prefer to use words to describe the intensity of their pain; these are termed verbal descriptor scales. Another variant that may be useful in the elderly or cognitively impaired are scales with drawings of faces, ranging from a contented smiling face to a distressed-looking face.

Single-dimensional scales are quick and simple to use, an important benefit in the acute setting when repeated measures are needed over a brief period of time. One disadvantage is that they attempt to assign a single value to a complex, multidimensional experience. Another is that patients can never know if the present experience is the “worst.” If a value of “10” is chosen and the pain worsens, the patient has no means to express this.

Several multidimensional scales exist that attempt to assess various aspects of the patient’s pain experience (eg, McGill Pain Questionnaire, Brief Pain Inventory). These multidimensional scales take into account the complex nature of pain. However, in the inpatient setting, they are too time consuming for rapid or repeated use. One compromise is to address a limited number of the dimensions of pain, using a few single-dimensional scales to address issues that are important to hospitalized patients—pain, anxiety, depression, anger, fear, and interference with physical activity.

Diagnosis

The history of the patient in pain includes the pain’s location and the presence of radiation from the primary site. Intensity should be determined using appropriate scales, as already described. The patient should describe the pain’s character (eg, aching, burning, dull, electric-like, sharp, shooting, stabbing, tender, throbbing). This may provide clues to diagnosis (Table 49-4). Does the pain have a pattern (constant, intermittent, or better or worse at certain times of day) and aggravating and alleviating factors? Does the pain have an impact on functional status? Are the patient’s activities of daily living affected as an outpatient, or is it hampering their ability to cough, get out of bed, and ambulate while in the hospital? The patient’s prior analgesic history, in particular, what therapies have either worked or not worked in the past, helps to decide what agents may be effective now. Exact doses of ongoing analgesics should also be determined.

| Pain Mechanism | Character | Examples | Treatment Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic |

|

|

|

| Visceral |

|

|

|

| Neuropathic |

|

|

|

The patient’s medical history should be obtained. Medical conditions that cause pain include cancer, diabetes, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, herpes zoster (shingles), and spinal cord injury. Psychological conditions may adversely impact a patient’s pain experience and need appropriate diagnosis and therapy. These include anxiety (especially in acute pain states), depression (most prevalent in persistent pain states), fear, catastrophizing (assuming the worst-case scenario), and personality disorders. A family history that is positive for substance abuse in the patient’s relatives is a risk factor for addiction in the patient. A social history positive for alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs may indicate a need to prescribe agents to prevent withdrawal (ie, benzodiazepines or nicotine patches). Even patients with a history of addiction still need to be appropriately treated for pain in the acute setting. In this setting, it may be useful to enlist the help of a psychiatrist or psychologist trained in addiction management.

A directed physical examination of the painful site, and a generalized physical exam of the patient as appropriate, should be performed. Pain (especially acute) may be associated with tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, and tachypnea. However, since sympathetic activation is a common and nonspecific finding in hospitalized patients, it offers little help in the diagnosis and treatment of pain in an awake, competent patient. These measures may be used as surrogates in patients who cannot express their pain experience. However, it is important to remember that patients may not exhibit any alterations in vital signs despite significant levels of pain, especially patients who have persistent pain.

|

Diagnostic tests to determine the etiology of pain may be useful in some situations (eg, radiographs to assess for fracture, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to diagnose nerve impingement in the spinal cord, or electromyography (EMG) to diagnose a neuropathy). However, normal test results should not be used to discount a patient’s report of pain.

Cardinal Principles of Pain Management

Pain is a subjective phenomenon, resulting from the filtering of nociceptive input through the affective (limbic system) and cognitive processes unique to each individual. The patient’s report of pain must be respected and believed. As pain is an affective and cognitive experience, the placebo response to analgesics is real and may be helpful. However, using the placebo response does not mean misleading patients, or administering an inactive substance to determine whether they are lying or to punish them. Rather, the placebo effect in contemporary medicine is that patient belief in a particular therapy makes it more likely to work. Physician attempts to truthfully “talk up” genuine attempts at analgesia are thus likely to enhance the effects. The reverse is also true. If a patient states that a particular therapy “never works for them,” it is less likely to be effective.

The patient’s pain level and degree of pain relief should be assessed appropriately and regularly. Pain should be treated quickly. Therapy should not be withheld while the diagnosis is unclear; pain treatment does not impede the ability to diagnose disease. A comprehensive plan should be used that addresses the multidimensional aspects of pain. This may require an interdisciplinary team approach (eg, hospitalist, pain specialist, anesthesiologist, surgeon, psychiatrist or psychologist, and physical therapist), especially for patients with persistent pain.

The analgesic plan should be discussed with the patient and, when appropriate, the patient’s family. The patient’s expectations for pain management should be understood, and patients should be offered reasonable goals for therapy. A multimodal approach for managing pain, employing both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic measures, is better than using just one modality. This approach allows for optimal analgesia with the lowest incidence of side effects. Clinicians should be familiar with several agents within each class of analgesics, including possible side effects, because individual responses vary greatly.