Introduction

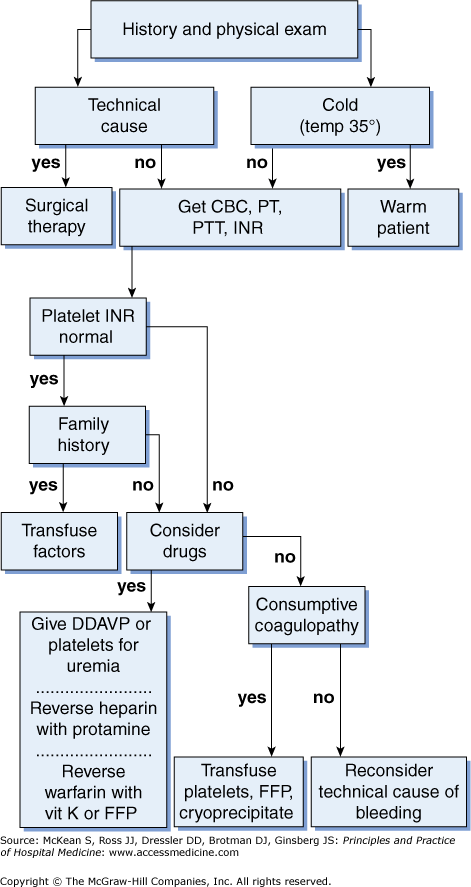

Postoperative bleeding is a dreaded surgical complication. More often than not you will hear, “It was dry when we closed…” as your surgical colleagues struggle to identify the source. Risk factors include trauma, coagulopathy, or factor deficiency, which may be congenital or acquired from malnutrition, antibiotic use, or liver disease. Hospitalized patients are commonly anticoagulated prior to surgery. Patients at risk should have a preoperative evaluation including a complete blood count, liver function tests, prothrombin time, activated partial prothrombin time, and international normalized ratio (Figure 45-1). Patients with platelet dysfunction from aspirin, antiplatelet agents, or uremia are also at increased risk of postoperative hemorrhage.

Surgical bleeding is usually from a blood vessel that was improperly occluded or was in spasm during surgery but is no longer in spasm and is bleeding into the surgical space. Nonsurgical bleeding is associated with coagulopathy and should be addressed medi-cally with normalization of clotting factors that may require transfusion or other agents that are discussed in detail below.

Ideally, hemostasis is achieved before the patient leaves the operating room (OR). However, patients who have received anticoagulation during surgery or experienced large blood loss during surgery are at risk for ongoing bleeding or rebleeding. Significant blood loss is expected with cardiopulmonary bypass and vascular procedures in which intravenous anticoagulation is routinely administered intraoperatively, as well as hepatic, obstetric, and large orthopedic procedures. Emergent and urgent procedures are also associated with higher blood loss. These patients are placed at high risk due to coagulopathy and a bloody surgical field that can obscure the surgeon’s ability to identify all bleeding points.

Postoperative bleeding should be suspected in any postoperative patient with hypotension, low urine output, or tachycardia. Even if these can be explained by other events, a complete blood count (CBC) is in order to rule out bleeding as a consideration. If bleeding is present, transfusion with blood and crystalloid to maintain blood volume are in order. Resuscitation should commence as you are looking for a source.

Postoperative bleeding should be suspected in any postoperative patient with hypotension, low urine output, or tachycardia.

|

Physical exam may reveal signs of shock as well as a tense or tender abdomen in the case of intra-abdominal bleeding, or a tense compartment after extremity surgery. Bleeding in the retroperitoneum may not be immediately obvious and should be suspected in aortic or prostate surgery. Bleeding may also not be obvious in obese patients. Drains left in the surgical bed may have bloody output. Cardiac and thoracic patients should have their chest tube output followed closely. If there is no chest tube in place, a chest X-ray will demonstrate a hemothorax. No matter the potential source, the operating surgeon should be notified immediately about any change in the patient’s condition.