KEY POINTS

The diagnosis of acute pericarditis should be made on the basis of typical chest pain symptoms, the presence of a pericardial friction rub, and electrocardiographic abnormalities, which are distinctive from changes due to myocardial ischemia.

Although a comprehensive evaluation is usually warranted in patients with acute pericarditis, the diagnostic yield is low with causes identified in less than 20% of patients.

High-dose nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and adjunctive colchicine are effective medical therapy for acute pericarditis, except in episodes due to acute coronary syndromes where NSAIDs are contraindicated.

Pulsus paradoxus is a bedside finding of cardiac tamponade that arises from compromise in left ventricular stroke volume during inspiration and a subsequent fall in stroke volume.

Echocardiography is the primary diagnostic modality for tamponade. Signs include diastolic inversion or collapse of the right atrium and right ventricle, ventricular septal shifting with respiration, enlargement of the inferior vena, and respiratory variation in transmitral flow.

In patients in whom invasive monitoring is available (eg, Swan-Ganz catheter) cardiac tamponade manifests as blunting or absence of the y descent, elevation in filling pressures, tachycardia, and reduced cardiac output.

The diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis can be made with echocardiography in most patients, with invasive catheterization reserved for patients in whom the clinical findings and noninvasive studies cannot definitively establish the diagnosis.

In the vast majority of patients with constrictive pericarditis, cardiac surgery with pericardiectomy is the definitive treatment for relief of heart failure.

The pericardium is a fibroelastic sac comprised of parietal and visceral layers that normally contain 15 to 50 mL of plasma ultrafiltrate. Pericardial disorders can be broadly categorized into the clinical entities of acute pericarditis (with or without effusion), cardiac tamponade, and constrictive pericarditis.

ACUTE PERICARDITIS

Acute pericarditis may occur in isolation or as part of a systemic disorder. Although there are a variety of etiologies, the majority of cases are idiopathic or presumed to be viral or autoimmune in origin. In developing countries and susceptible individuals, tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus are common causes of acute pericarditis.

The diagnosis of acute pericarditis is made on the basis of typical chest pain symptoms, the presence of a pericardial friction rub, distinctive electrocardiographic abnormalities, and supportive data from noninvasive testing. The clinical presentation is characterized by chest pain in 90% to 95% of cases, with additional symptoms attributable to the underlying etiology. Chest pain due to acute pericarditis is typically anterior and sharp, with aggravation related to maneuvers that increase pericardial pressure (eg, cough, inspiration, orthostasis). These characteristics may be useful in distinguishing pericarditis from acute myocardial ischemia, but these features also are frequently present in other chest pain syndromes, such as pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, costochondritis, and gastroesophageal reflux.

A pericardial friction rub is the hallmark physical sign of pericarditis, and may be present in patients with or without a pericardial effusion. The intensity and location of these rubs can vary, being present in 35% to 80% of patients with acute pericarditis. Pericardial friction rubs are best heard during held end-expiration with the patient leaning forward. This maneuver allows distinction from a pleuropericardial or pleural rub, which is present only during respiration. Three components of a pericardial friction rub may be auscultated, with each component attributable to atrial systole, ventricular systole, and early rapid ventricular diastolic filling.

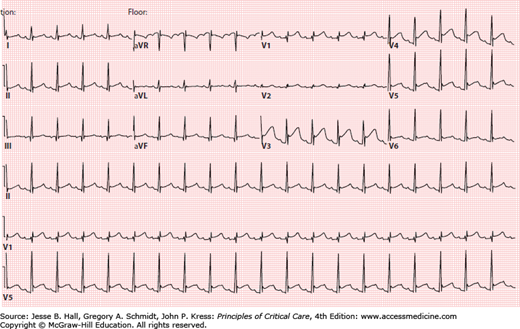

Electrocardiographic changes frequently occur in patients with acute pericarditis, and indicate inflammation of the visceral pericardium (or epicardium). Typical electrocardiographic changes are PR-segment abnormalities due to atrial involvement with elevation in lead aVR and depression in other leads, and concave upward ST-segment elevation (Fig. 40-1). Although the electrocardiographic abnormalities usually are diffuse, certain etiologies of acute pericarditis (eg, trauma, cardiac perforation) may result in localized changes. Other frequent electrocardiographic findings are sinus tachycardia and electrical alternans. Several features help to distinguish the electrocardiographic changes of acute pericarditis from myocardial ischemia and early repolarization, and should be routinely employed in the evaluation of these patients (Table 40-1).

Electrocardiographic Features That Helped to Differentiate Acute Pericarditis From Myocardial Ischemia or Infarction

| Acute Pericarditis | Myocardial Ischemia | |

|---|---|---|

| Contour of ST segment | Concave upward | Convex upward |

| ST-segment lead involvement | Diffuse | Localized |

| Reciprocal ST-T changes | None | Yes |

| PR segment abnormalities | Yes | No |

| Hyperacute T waves | No | Yes |

| Pathologic Q waves | No | Yes |

| Evolution | ST-segment change initially, then T wave | T-wave alteration initially, then ST segment |

| ˙Qт prolongation | No | Yes |

Other noninvasive tests can be used to support the diagnosis of acute pericarditis, but are more limited in their sensitivity and specificity. Inflammatory markers, such as leukocyte count, sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, may be elevated. Increases in biomarkers of cardiac injury (cardiac troponin I or T) indicate concomitant myocarditis (ie, myopericarditis). The chest x-ray may show cardiomegaly when a large pericardial effusion is present. Echocardiography should be performed in all cases of suspected acute pericarditis to evaluate for the presence of hemodynamically significant pericardial effusion. Echocardiography (or other cardiac imaging) may demonstrate a pericardial effusion in 50% to 60% of patients, but its absence does not rule out the diagnosis.

The goals of clinical management of the patient with acute pericarditis are identification and treatment of potential etiologies, symptom relief with anti-inflammatory agents, and recognition and treatment of hemodynamically significant pericardial effusions. The majority of patients with acute pericarditis can be managed in the ambulatory clinic. Clinical features indicative of increased risk and need for hospitalization are the presence of fever, leukocytosis, acute trauma, cardiac biomarker elevation, immunocompromised host, oral anticoagulant use, and large or hemodynamically significant pericardial effusions.

Although a comprehensive evaluation is usually warranted in patients with acute pericarditis, the diagnostic yield of standard testing is low with specific causes identified in less than 20% of cases. Important etiologies to consider for further evaluation are those that require specific therapy, such neoplastic disorders, autoimmune disease, trauma (eg, postsurgical), and infection (eg, tuberculosis). The vast majority of cases of acute pericarditis are viral or idiopathic, and thus are usually benign and responsive to anti-inflammatory drugs. For patients with a concomitant pericardial effusion, pericardiocentesis may be considered. Pericardiocentesis can assist in diagnosis when other testing is inconclusive, and is indicated for treatment of cardiac tamponade or drug-refractory, symptomatic pericardial effusions.

Targeted therapy of the underlying etiology of acute pericarditis is indicated when a cause is identified and treatment is appropriate (eg, tuberculosis, uremia, thyroid disease). For analgesia and treatment of the pericardial inflammation, NSAIDs are the mainstay of medical therapy. The properties of these drugs provide effective relief in 70% to 80% of patients. The efficacy of medical therapy varies according to the underlying etiology, with response rates greatest among those with idiopathic or presumed viral causes. It is important to note that relatively high doses of these medications are required for them to exhibit their anti-inflammatory effect (eg, aspirin, 650-1000 mg every 6-8 hours; ibuprofen, 400-800 mg every 8 hours; indomethacin, 50 mg every 8 hours). Furthermore, although these drugs can result in acute relief of symptoms, slow tapering over a period of 2 to 4 weeks is recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence of inflammation. Of note, for pericarditis associated with myocardial infarction, NSAIDs other than aspirin should be avoided due to their effect of impairment of myocardial healing and potential for increasing the risk of mechanical complications.

Colchicine (0.5-1.2 mg/d for 3 months), in addition to NSAIDs, is an effective adjunctive therapy for acute pericarditis. The efficacy of colchicine has been demonstrated in several randomized and retrospective studies, which have shown lower rates of treatment failure (11.7% vs 36.7%) and recurrent pericarditis (10.7% vs 32.3%) when used in conjunction with standard NSAID therapy.1-3 Colchicine is generally well tolerated; side effects include gastrointestinal distress and, less commonly, bone marrow suppression, myositis, and liver toxicity.

Glucocorticoids are reserved for acute pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, for those in whom there are contraindications to the use of NSAIDs, and in patients with specific disease states that are potentially amenable to glucocorticoid use (eg, autoimmune disorders, uremic pericarditis). Prednisone (0.25-0.50 mg/kg per day over 3 months) may be used in these circumstances with a slow taper beginning at 2 to 4 weeks and careful attention to occurrence of steroid side effects. Studies have associated glucocorticoid use with greater risk of recurrence, but these reports have been hampered by the tendency to use these agents in patients with pericarditis refractory to other therapies.

CARDIAC TAMPONADE

Cardiac tamponade occurs when intrapericardial pressure exceeds intracardiac pressure, resulting in impairment of ventricular filling throughout the entire diastolic period. Virtually any disorder that causes pericardial effusion can result in cardiac tamponade. The most common atraumatic etiology is malignancy, with breast and lung cancer being the most frequent. Other important causes are complications of invasive cardiac procedures, idiopathic or viral pericarditis, aortic dissection with disruption of the aortic valve annulus, tuberculosis, uremia, and pericarditis or ventricular wall rupture from myocardial infarction.

The pericardium normally contains <50 mL of fluid between the parietal and visceral layers, with intrapericardial pressure approximating intrapleural pressure (−5 to +5 cm H2O). The amount and rate of fluid accumulation determine the hemodynamic effects of a pericardial effusion.4,5 Intrapericardial pressure rises with fluid accumulation and pericardial restraint. Venous return and ventricular filling becomes impaired once the intrapericardial pressure exceeds the filling pressure of the cardiac chambers. This impairment precipitates a reduction in cardiac output, followed by increases in pulmonary venous and jugular venous pressures. With inspiration, there is a fall in the driving pressure to fill the left ventricle, subsequently leading to a reduction in ventricular filling and stroke volume. The fall in left ventricular stroke volume during inspiration manifests as a relative decrease in pulse pressure or peak systolic pressure, which is the hallmark finding of pulsus paradoxus in patients with cardiac tamponade.

There are uncommon clinical presentations of cardiac tamponade. Cardiac tamponade may be localized, when a loculated pericardial effusion is tactically located to impair ventricular filling. This manifestation may occur after cardiac surgery or other postoperative settings. The loculated effusion may be present in the posterior pericardial space adjacent to the atria, which poses challenges for detection by echocardiography. Posterior loculated effusions should be suspected in a postoperative patient with hemodynamic instability.

Low-pressure cardiac tamponade

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree