PERFORATED HOLLOW VISCUS

CASE SCENARIO

An 80-year-old woman with hypertension presents to the emergency department with the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain. The pain began abruptly 1 hour prior to her arrival, without any apparent antecedent events. She complains of excruciating, diffuse, sharp abdominal pain that is constant, does not radiate, and exacerbates with movement, especially during the ambulance ride to the hospital. She had a single episode of emesis, but otherwise denies any associated symptoms.

The patient is afebrile, but tachycardic and tachypneic, and has relative hypotension with systolic blood pressure in the 90s. She appears anxious, diaphoretic, and uncomfortable. Her abdomen is distended, tympanitic, and diffusely tender, with rebound and guarding in all quadrants. Her laboratory tests reveal a leukocytosis of 16,000 with a bandemia, glucose of 240, and lactate of 3.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Abdominal pain is a leading reason for emergency department visits.1 Acute abdominal pain accounts for 40% of emergency surgical hospital admissions, and a large proportion of these patients have perforated hollow viscus or impending gastrointestinal perforation.2 In Western countries, the incidence of gastrointestinal perforation for patients not taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is 0.1 per 1000 person-years.3 Early diagnosis and intervention are key, as mortality for patients with hollow viscus perforation and secondary peritonitis exceeds 20%.2,4,5

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Perforated hollow viscus is characterized by loss of gastrointestinal wall integrity with subsequent leakage of enteric contents. Direct trauma or tissue ischemia and necrosis lead to full-thickness disruption of the gastrointestinal wall and perforation. Perforation may occur at any site within the alimentary tract, from mouth to anus, and the site of the perforation largely determines the patient’s presentation and clinical course.

Exposure of the normally sterile peritoneal cavity to intraluminal contents causes either a chemical peritonitis or secondary bacterial peritonitis. Proximal perforations can leak acidic gastric or caustic biliary or pancreatic secretions, and the resultant chemical peritonitis triggers a robust systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) with the potential for rapid clinical deterioration.2,6 In contrast, distal perforations leak intraluminal contents that are more chemically inert, but that carry a high bacterial load. Their clinical course may be more insidious, with development of purulent or fecal peritonitis and intra-abdominal abscess or phlegmon.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Perforated hollow viscus should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient presenting with an acute abdomen. Often, patients describe initially localized, visceral pain that becomes diffuse, dramatic, and severe, and progresses to peritonitis. Alternatively, patients with advanced age, obesity, immunosuppression, or contained perforation may present with minimal findings. Associated symptoms are nonspecific and may include fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, change in bowel habits, weight loss (for contained perforation), syncope, dizziness, and dysuria.

Because patients with perforated hollow viscus may present in a moribund state and have the potential for rapid clinical deterioration, the physical examination begins with an assessment of the patient’s overall state and clinical stability. For patients who appear ill, the initial assessment focuses on securing the airway and supporting breathing and circulation. Vital sign abnormalities, including tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension, may be the first clues that the patient’s physiologic status is compromised and that the patient is in SIRS, sepsis, or even septic shock. Laboratory values may reveal septic shock with multi-organ failure; metabolic acidosis is particularly concerning. In addition to a thorough abdominal examination, the groin, perineum, and rectum should be evaluated. For female patients, pelvic examination should be considered.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

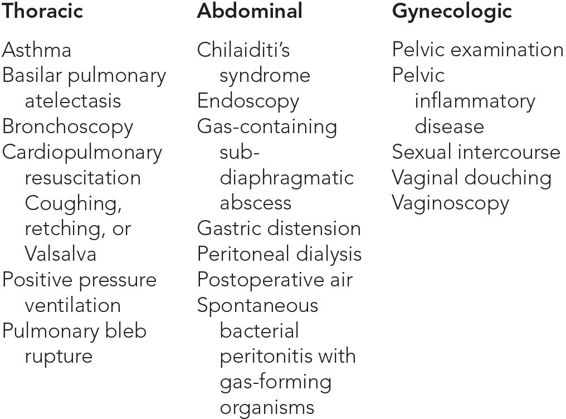

See Tables 6–1 and 6–2.

Specific Diagnoses

Specific Diagnoses

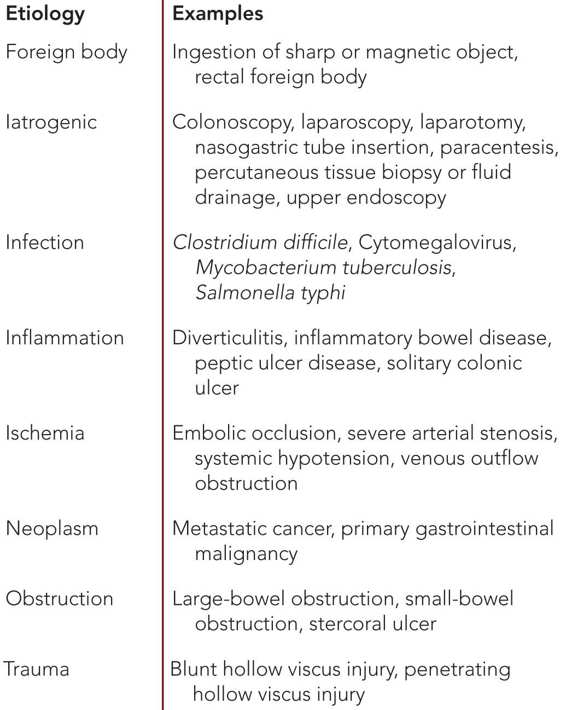

See Tables 6–3 through 6–6.

WORKUP AND CHOICE OF IMAGING

Plain film radiography remains the preferred initial diagnostic study for patients with suspected perforated hollow viscus. Including multiple views, such as upright chest, supine abdominal, and left lateral decubitus abdominal, is ideal. As little as 1 cc of free air can be detected with abdominal plain films,15 but sensitivity varies with the site of hollow viscus perforation; 45% to 56% of gastroduodenal, 7% to 14% of small intestinal, and 27% of large intestinal perforations have pneumoperitoneum on plain films.7,16 Traditional radiographic signs are most likely to be observed in the presence of large-volume pneumoperitoneum. When perforations are very small, are self-sealed, or are contained by other organs, pneumoperitoneum may not be apparent on plain films.

Ultrasound is useful when limited radiation exposure is desired, particularly for pregnant women or children, or for patients who are unable to sit or stand erect for upright plain films. One caveat is the similar appearance on ultrasound of both pneumoperitoneum and intraluminal gastrointestinal air. Despite this challenge, ultrasound is an under-appreciated diagnostic tool that can detect as little as 2 cc of air, with a reported sensitivity of 93% to100% and specificity of 64% to 99%.16,18–20 When using ultrasound, a linear-array, 10- to 12-MHz transducer is used to examine the patient in the supine position. The right upper quadrant, where intestine is less likely to be interposed between the liver and anterior abdominal wall, and the midline are the two windows where pneumoperitoneum is best visualized. The diagnostic accuracy of abdominal ultrasonography for the detection of hollow viscus perforation is operator dependent, and may be less reliable for obese patients.

When plain films are equivocal or the cause is unclear in a stable patient, computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis offers a greater sensitivity of 96% to 100% for diagnosing hollow viscus perforation.21–25 The benefits of CT scan must be weighed against the time lost in performing the study, with the possible delay in intervention. Additional considerations include the financial cost, the additional radiation burden, and the possibility that the results may not change management. CT scan is rarely, if ever, an appropriate study in an unstable patient or a patient at imminent risk for clinical deterioration. However, in stable patients, CT scan may guide operative planning by identifying the site of perforation, or may help avoid an unnecessary laparotomy altogether.

Fluoroscopy studies with enteric contrast, such as upper gastrointestinal series or contrast enema studies, can also confirm the diagnosis and identify the site of perforation. Water-soluble contrast is preferred, and barium is avoided because of the risk of barium peritonitis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not traditionally used in the evaluation of patients with suspected hollow viscus perforation because the time required to complete the study can lead to unsafe delays in diagnosis and treatment. MRI does not appear to offer any advantage over CT in ability to detect pneumoperitoneum,26 but may be useful for pregnant or pediatric patients.

IMAGING FINDINGS

X-Ray

X-Ray

The hallmark finding on an upright plain film is air beneath the diaphragm, identifiable as lucency between the diaphragm and liver or stomach. Table 6–7 describes the signs of pneumoperitoneum on plain film in detail (Figures 6–1 through 6–7).