Figure 14.1 Anatomy of the pelvis. (a) The pelvis may be divided into the true pelvis and the false pelvis. The true pelvis is bounded anteriorly by the pubic symphysis and the pubic rami, posteriorly by the sacrum and coccyx, and inferiorly by the perineal musculature. Within the true pelvis are the bladder, the uterus, and the ovaries. (b) Blood supply to the uterus and ovaries. Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press.

Technique

The pelvic organs can be imaged in both a transabdominal and a transvaginal approach. The technique should be chosen based upon anticipated findings and organs of interest, as well as the age and sexual maturity of the patient. Transabdominal scanning may provide a broader field of view, as well as greater depth in imaging, and is useful in visualizing the ovaries, their vasculature, and the surrounding pelvic floor. Transvaginal scanning offers a greater resolution and more detailed imaging of the anatomy close to the transducer, including the cervix and endometrium. Each scanning technique and transducer type should be used to its full advantage and be allowed to complement one another, rather than limiting their utility by applying them in isolation. Also refer to Chapter 13 for the technique.

Begin with a transabdominal scan in order to gain a global impression of the positioning of the uterus. On occasion, the transabdominal view may also allow for better imaging of the adnexa and more lateral structures, as its range of motion is not as limited as with the transvaginal approach. Then, it is useful to perform the transvaginal examination when more detail of small structures, such as the ovaries, is necessary. It is important to image all pelvic structures in two planes, e.g. sagittal and transverse (transabdominal), or sagittal and coronal (transvaginal). This is the best means of gaining a view of three-dimensional objects such as the uterus and ovaries. The bladder plays an important role in both transabdominal and transvaginal scanning. A full bladder on transabdominal scan will act as an acoustic window, and allow for the improved visualization of structures such as the uterus and ovaries. An empty bladder on transabdominal scan may allow the uterus to fold up upon itself, distorting the anatomy and the relationship betweens structures. In contrast, a full bladder on endovaginal scanning may not only be uncomfortable for the patient, but may also obscure findings by retroverting the uterus and pushing it out of view or by taking up too much space to allow for the visualization of important structures.

Point-of-care questions

Transabdominal

Transducer selection and orientation: transabdominal

Transabdominal scanning allows for the visualization of organs further away from the transducer. A low-frequency (2–5 MHz) curvilinear transducer is utilized, which allows for deeper penetration of sonographic waves through the abdominal musculature and soft tissues.

Transabdominal images of the uterus and adnexa are obtained by placing the transducer immediately superior to the pubic symphysis, using the fluid-filled bladder as an acoustic window. A transverse image is obtained by placing the transducer with the indicator oriented towards the patient’s right side (Figure 13.4a). A sagittal image is obtained by rotating the indicator cephalad directly towards the patient’s head (Figure 13.5a).

Patient position and preparation: transabdominal

For transabdominal scanning, the patient is positioned comfortably in a supine position. This examination should, whenever possible, be performed on patients with a full bladder, since it provides an acoustic window through which to visualize the uterus and ovaries. For additional comfort, consider having the patient flex her legs at the hips and knees. This position also enhances the ability to utilize graded compression.

Ultrasound imaging: transabdominal

In the transverse view, the bladder appears as a dark, hypoechoic, oval or trapezoidal structure lying above the uterus (Figure 13.4b,c). In the sagittal view, the bladder appears as a wedge-shaped anechoic structure adjacent to the uterus. The bladder appears on the right and the uterus appears on the left when looking directly at the monitor (Figure 13.5b,c). The fluid-filled bladder is used as an acoustic window to scan the pelvic organs. As a fluid-filled structure, the bladder allows full through-transmission of the ultrasound beams to scan the deeper anatomy. A full bladder also aids indirectly by physically pushing bowel loops out of the way of the ultrasound window. When the bladder is empty, bowel loops may obscure the view by scattering of the echoes as they pass through the air-filled intestines, distorting the more distal image. It is important to remember that, due to the low attenuation of sound waves as they travel through the fluid-filled bladder, posterior acoustic enhancement may occur distal to the bladder. The image can be adjusted by decreasing the far-field gain (or time gain compensation), preventing the hyperechoic section behind the bladder from obscuring any important structures.

When scanning the pelvis for the presence of free fluid, such as in the case of a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst, the sonographer should be aware of the differing appearance that blood may have depending on the timing of the bleeding. While fresh blood will appear anechoic or hypoechoic (Figure 14.2), older pooled or clotted blood may appear more heterogeneous, with increasingly visible internal echoes as coagulation occurs. A collection of clotted blood may thus be confused with a loculated mass, bowel loops, or other anatomic structures.

Figure 14.2 Free fluid. Transabdominal, transverse pelvic ultrasound showing anechoic blood (*) posterior to the bladder (B), and anterior to the uterus (U).

Transvaginal

Transducer selection and orientation: transvaginal

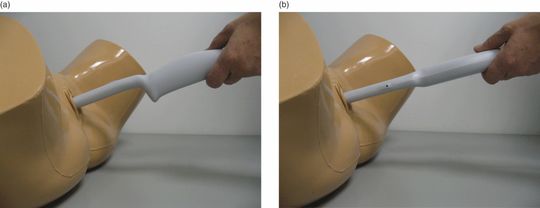

During transvaginal scanning, the pelvic anatomy of interest is much closer to the high-frequency transducer. The endovaginal or endocavitary probe therefore requires less depth penetration of the sound waves and employs a high frequency (5–9 MHz) which allows for higher image resolution. When using the endocavitary probe, identify the indicator prior to insertion. The sagittal view is obtained by pointing the indicator towards the ceiling (Figures 13.8, 14.3a). The coronal view is obtained by rotating the indicator counterclockwise, towards the patient’s right side (Figures 13.9, 14.3b).

Figure 14.3 Phantom model, transvaginal scanning. (a) Sagittal view, with the indicator pointed towards the ceiling. (b) Coronal view, with the indicator oriented towards the patient’s right side.

Patient position and preparation: transvaginal

Prior to the transvaginal scan, the patient should be asked to void and have an empty bladder. A full bladder on transvaginal scanning may not only be uncomfortable for the patient, but may also obscure findings by retroverting the uterus and pushing it out of view or by taking up too much space to allow visualization of important structures. The patient is placed in the lithotomy position to provide the sonographer with access to the vaginal introitus, as well as to allow for mobility of the transducer. Ideally, this portion of the ultrasound is performed in conjunction with the pelvic examination, in order to maximize the efficiency of the patient’s evaluation.

Prior to insertion, an endocavitary probe should be covered with a clean, impermeable probe cover (i.e. glove, condom, or commercially available cover), in order to reduce contact and contamination with bodily fluids. There should be two layers of gel: one inside the probe cover, and a sterile lubricant gel on top of the covered transducer (Figure 13.7). In addition, it is crucial that the transducer be properly disinfected with chemical high-level disinfection immediately after each examination, in order to further minimize the risk of disease transmission. Such examples include immersion of the transducer in Cidex® or a sodium hypochlorite solution.

Ultrasound imaging: transvaginal

The transvaginal ultrasound examination can be useful in determining specific regions of patient discomfort, and the mobility of organs such as the ovaries. For example, adhesions from inflammation in the case of PID may reduce the mobility of the ovaries. Similarly, the ability of a mass to move with or separate from an adjacent ovary may aid in determining the etiology of this mass.

First, identify the longitudinal view of the uterus, in the sagittal view. The indicator is pointed towards the ceiling (Figure 13.8). Then, in order to obtain the coronal view, rotate the transducer counterclockwise, with the indicator towards the patient’s right side (Figure 13.9). Find a plane of the uterus such that the uterine stripe is visible. Then, identify the ovaries by moving the transducer towards the lateral fornices. The ovaries will have a “chocolate chip cookie” appearance (Figure 14.4a).

Figure 14.4 Normal ovaries. (a) Transvaginal scan of the ovaries demonstrating the “chocolate chip cookie” appearance. (b) Color Doppler showing normal flow to the ovary. Images courtesy of Madhuri Kirpekar, MD.

Color Doppler imaging may add significant information in pelvic pathology. While evaluating for ovarian torsion, color Doppler is utilized to assess for venous and arterial flow (Figure 14.4b). It is important to remember that the presence of venous and arterial flow does not “rule out” an ovarian torsion. In addition, color Doppler may be utilized in order to determine the etiology of masses, depending on their vascularity. Hyperemia may suggest inflammation and edema, such as in irritation of the endometrium and the adnexa in PID; while absence of vascularity may distinguish between a simple ovarian cyst and a more complex mass lesion.

Education and training

Training for transabdominal pelvic ultrasonography is easily performed with healthy volunteer models. However, it is often difficult to train clinicians in the use of transvaginal ultrasonography, and challenging to obtain live-patient model volunteers. Therefore, simulation has become increasingly important in the training of clinicians. Commercially available pelvic ultrasound trainers are available, which simulate pelvic anatomy and allow for transvaginal scanning (Figure 14.3). A recent study by Girzadas et al. introduced the combination of a high-fidelity scenario with a pelvic task trainer in order to train emergency medicine residents. Overall, both faculty and residents felt that this combination improved residents’ skill in obtaining and interpreting transvaginal ultrasound images, and improved their overall education experience.

Scanning tips

Pitfalls

- An empty bladder on transabdominal scan may allow the uterus to fold up upon itself, distorting the anatomy and the relationship between structures.

- A full bladder on endovaginal scanning may not only be uncomfortable for the patient, but may also obscure findings.

- One of the main pitfalls for the novice sonographer is failing to verify findings in two planes. For example, a blood vessel seen in cross-section may be confused with a cyst if the longitudinal axis is not evaluated to allow the sonographer to see the tubular shape of the vessel.

- While fresh blood will appear hypoechoic, older pooled or clotted blood may appear more heterogeneous, with increasingly visible internal echoes as coagulation occurs. A collection of clotted blood may thus be confused with a loculated mass, bowel loops, or other anatomic structures.

- A critical pitfall is relying on the visualization of venous or arterial flow on Doppler ultrasound to rule out ovarian torsion.

Tips to improve scanning

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree