Pediatric Thermal Injury

Laura Snell MD

Howard Clarke MD, PhD, FRCS, FAAP, FACS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Many systemic derangements caused by burn injury contribute to fluid shifts.

Significant fluid shifts result in burn wound edema and systemic hypovolemia.

Loss of cutaneous barrier function.

Insensible losses.

Increased capillary permeability.

Local in all burn wounds, systemic if >25% TBSA (total body surface area).

Hypoproteinemia.

Increased fluid shift from vessels to interstitial tissues.

Release of arachidonic acid cascade metabolites including prostaglandins, histamine, serotonin.

Hormonal derangements (increase in ADH and aldosterone).

BURN CLASSIFICATION

Early assessment and documentation of burn depth, extent, and involvement of hands/face/perineum is very important for treatment planning and must be done.

Depth

First degree/superficial:

Red, dry, painful.

Will heal after several days, no scar.

Second degree/partial thickness:

Red, wet, very painful.

May be superficial or deep partial thickness.

Will likely heal after days to weeks of adequate wound care including debridement, daily wound check and dressing changes.

May require skin grafting and may scar.

Third degree/full thickness:

Leathery, dry, insensate, waxy.

Will not heal without excision and grafting.

Fourth degree:

Involves underlying subcutaneous tissue, tendon, bone.

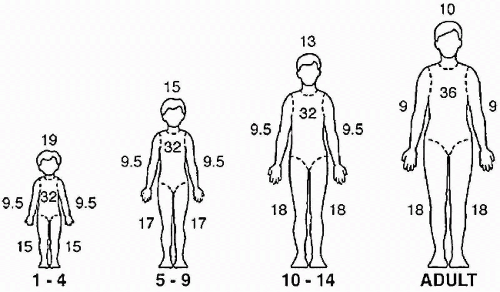

Total Burn Surface Area (TBSA) (Fig. 14-1)

Lund—Browder chart.

Age-specific.

Rule of nines (Fig. 14-1).

Assuming adult body proportions—appropriate for use in teenagers.

Larger head and neck in proportion for younger children and infants.

Exclude first-degree burns when calculating TBSA.

PEDIATRIC BURNS: INITIAL MANAGEMENT

Primary Survey

Airway Management

Airway is first priority during primary survey.

Must be secured prior to transport.

Suspect inhalation injury if:

The fire occurred in an enclosed space.

Patient has:

Carbonaceous sputum.

Singed nasal hairs or eyebrows.

Hoarseness or stridor.

Elevated carboxyhemoglobin level (>10%).

Confirm airway injury with bronchoscopy at the bedside.

Hot liquid aspiration can also cause airway compromise.3

Indications for intubation:

Inhalation injury

Stridor.

Respiratory distress.

PaO2 < 60 mmHg, PaCO2 > 55 mmHg.

Need for transport to another facility.

Significant facial ± neck burns.

Anticipated aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Important to secure the endotracheal tube (ETT) at the time of intubation.

Do not cut the ETT shorter as facial edema will likely progress.

Ensure the ETT is secured properly.

Consider use of reinforced ETT.

24-gauge wire around the molars and then around the tube.

Do not use suture material (not strong enough).

See Chapter 3 on Airway Management for details.

Fluid Resuscitation

Important to establish early secure venous access.

Can be difficult in the hypovolemic patient.

May require intraosseous access to begin resuscitation.

See the “Definitive Management” section later in this chapter for details.

Aggressive fluid resuscitation with normal saline required for burns >15%.

Burns <15% are generally not associated with extensive capillary leak.

Encourage PO fluid intake.

Closely monitor urine output. Goal = 1-2 mL/kg/hr.

Parkland resuscitation formula (Ringer lactate): 4 mL/kg/%TBSA.

Note: Time zero for fluid resuscitation = time of burn injury.

An estimation of fluid requirements for the initial 24 hours following a significant burn injury ABOVE normal maintenance requirements.

Give first half of calculated volume over 8 hours from time of injury.

Give the remaining half of calculated volume over the following 16 hours.

Remember to consider other ongoing losses as well (e.g., vomiting).

Monitor urine output closely and adjust rate of fluid infusion as needed for target urine output of 1-2 mL/kg/hr.

EVALUATION

History

Details of the events surrounding the injury.

Where did it occur? When did it occur? How did it occur?

Was anyone else injured?

What was the fluid involved—grease versus water/steam?

Symptoms:

Pain related to burns.

Chest pain, shortness of breath, coughing.

Vomiting or abdominal pain.

Dizziness or lightheadedness, syncope, headache, visual changes.

Extremity pain, numbness, tingling.

Past medical history:

Underlying cardiac, respiratory, or neurological disease.

Tetanus status.

NPO status.

Physical Examination/Burn-Specific Secondary Survey

Neurologic exam:

Rule out intracranial trauma.

Carbon monoxide poisoning.

Administer 100% O2 until COHB <10%.

See Chapter 15 on Smoke Inhalation for further details.

Assess for and manage pain/anxiety.

See Chapter 18 on Pain Management for further details.

Ophthalmologic and otolaryngologic exam.

Cornea:

Fluorescein exam to rule out corneal injury.

External ear:

Assess for burns and exposed cartilage.

Chest:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree