Pediatric Dermatology

John B. Lampe

Dermatologic disease and normal skin variants are common considerations in a pediatric practice, accounting for up to 10% to 15% of pediatric office visits. For the physician who is familiar with common skin conditions and the available treatment options, the management of these conditions can be an enjoyable part of clinical pediatrics.

COMMON TRANSIENT NEONATAL SKIN CONDITIONS

Several common neonatal rashes are easily distinguished on close observation. Erythema toxicum (neonatorum) is possibly the most frequently encountered rash (Fig. 1.1). Appearing within the first 3 to 5 days of life, it resolves spontaneously in 1 to 2 weeks. The individual lesions are characterized by a central, small “welt” or pustule on a broader erythematous base and can appear anywhere on the body. The fact that they are individual lesions makes it possible to differentiate them from the clustered microvesicles of herpes simplex (which also yields a positive direct fluorescent antibody stain when the base of the lesion is scraped) and the wider pustules of impetigo (which can be confirmed by a positive Gram stain for neutrophils and the presence of gram-positive cocci in clusters or chains). For unknown reasons, a Wright stain of a scraping of erythema toxicum reveals predominantly eosinophils. No treatment of this rash is necessary.

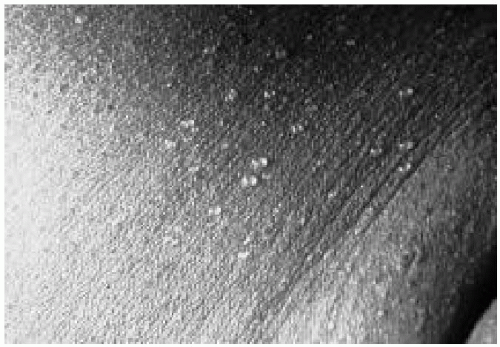

Miliaria (“prickly heat”) is another rash that is relatively common in the first few weeks of life (Fig. 1.2). Caused by keratin plugging of eccrine (sweat) glands in the skin, miliaria presents as an eruption of microvesicular lesions on the face, neck, scalp, or diaper area. If the eccrine obstruction is relatively deep in the epidermis, sweat can leak out of the duct and cause an inflammatory response, in which case the lesion has a red base. Treatment consists of dressing the infant in light clothes and avoiding excessive humidity.

Milia are white or yellow micropapules that develop when the pilosebaceous unit is obstructed by keratin/sebaceous material. They are most commonly found clustered on the nose, cheeks, chin, or forehead, and they resolve without treatment within several months.

ECZEMATOUS RASHES

Eczematous rashes are among the most frequently encountered skin disorders in children from infancy through adolescence. The neonatal form of seborrheic dermatitis often appears during the first several months of life. It may present as “cradle cap” and then extend to other areas of the skin where sebaceous glands are dense: the forehead and eyebrows, behind the ears, the sides of the nose, the middle of the chest, and the umbilical, intertriginous, and perineal areas in infants (Fig. 1.3). A lack of pruritus is characteristic of seborrhea. The individual lesions are often well-circumscribed plaques with greasy, yellow-to-orange overlying scales.

The lesions of infantile seborrhea often resolve by 8 to 12 months of age, but they can recur in childhood and especially in adolescence (in association with a hormonally related, general increase in sebaceous activity in the skin). Some dermatologists have proposed an association of seborrhea with skin colonization by Pityrosporum ovale, although it is unclear whether this is a primary or secondary phenomenon. The treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in infants is often expedited by controlling the scalp seborrhea with an antiseborrheic shampoo. In persistent cases of scalp seborrhea, one may consider treatment with 2% ketoconazole (Nizoral) shampoo. Once the scalp lesions are controlled, any residual skin lesions that do not resolve spontaneously can be treated with a brief course of a mild (1% hydrocortisone) topical steroid cream.

If a seborrheic-like rash is quite persistent or severe or is accompanied by anemia, adenopathy, or hepatosplenomegaly, consideration of a more systemic illness, such as histiocytosis, is appropriate.

Atopic dermatitis is the most often encountered chronic skin condition in pediatric practice (Fig. 1.4). The clinical term eczema, which is often used to indicate this diagnosis,

actually describes a clinical constellation of physical signs, including the following:

actually describes a clinical constellation of physical signs, including the following:

Figure 1.1 Erythema toxicum in a neonate. (See color insert.) |

Erythema

Microvesicles (often confluent)

Weeping and crusting

Thickening (lichenification) of the involved skin as a result of chronic scratching

Atopic dermatitis represents an inherited predisposition of the skin to become excessively dry, to itch, and to display the noted features of eczema. Besides an underlying defect of stratum corneum barrier function, there is also altered T-cell expression with resultant local expression of inflammatory cytokines. The incidence in children is now estimated at 20%, and the condition is seen more often at times of the year (winter in temperate or cold climates) when the air is dry. Atopic dermatitis often develops in conjunction with two other diagnoses of the so-called atopic triad— namely, asthma and allergic rhinitis (in the same patient or family members).

Figure 1.2 Microvesicular lesions representing miliaria. (See color insert.) |

Figure 1.3 Seborrheic dermatitis in an infant. (See color insert.) |

The pattern of distribution of atopic dermatitis often changes during the childhood years. Although it is often seen on the face in infants, it is found more often on extensor surfaces of the arms and legs in the first year of life, and in the more familiar sites of the antecubital and popliteal areas, front of ankles, neck, and face in older children and teenagers.

The treatment of atopic dermatitis strives to address the underlying physiologic events. Interrupting the “itch-scratch” cycle (e.g., with oral antihistamines or colloidal

oatmeal baths) is important. The frequent and liberal use of unscented topical moisturizers to combat dry skin is helpful, especially immediately after a bath with tepid water and mild soap, if any. Newer, more expensive “physiologic moisturizers” are now available that attempt to replenish depleted intracellular lipids in the epidermis. Actively weeping patches can be partially relieved with wet compresses soaked in aluminum acetate solution (Domeboro, Burow; available over the counter as tablets or powder packets). Inflamed (red, scaly) lesions are usually treated with a topical steroid cream or ointment until the inflammation is controlled. (Ointments are more potent, with better penetration of lichenified lesions that are not on the face or on intertriginous, occluded areas of skin). Topical calcineurin inhibitors that block T-cell transcription upregulating inflammatory modulators, such as tacrolimus (Protopic) ointment and pimecrolimus (Elidel) cream, are effective in the treatment of moderate or refractory cases of atopic dermatitis. These agents are safe to use even on delicate skin such as on the face or neck. These calcineurin inhibitors, however, are currently recommended for children older than 2 years of age, and as second-line agents to be used if topical steroid therapy and moisturizers are ineffective. Finally, being alert to the presence of possible secondary infection (especially Staphylococcus aureus) and treating such infection with a course of an effective oral antibiotic or topical mupirocin (if the lesions are more localized) often leads to significant improvement.

oatmeal baths) is important. The frequent and liberal use of unscented topical moisturizers to combat dry skin is helpful, especially immediately after a bath with tepid water and mild soap, if any. Newer, more expensive “physiologic moisturizers” are now available that attempt to replenish depleted intracellular lipids in the epidermis. Actively weeping patches can be partially relieved with wet compresses soaked in aluminum acetate solution (Domeboro, Burow; available over the counter as tablets or powder packets). Inflamed (red, scaly) lesions are usually treated with a topical steroid cream or ointment until the inflammation is controlled. (Ointments are more potent, with better penetration of lichenified lesions that are not on the face or on intertriginous, occluded areas of skin). Topical calcineurin inhibitors that block T-cell transcription upregulating inflammatory modulators, such as tacrolimus (Protopic) ointment and pimecrolimus (Elidel) cream, are effective in the treatment of moderate or refractory cases of atopic dermatitis. These agents are safe to use even on delicate skin such as on the face or neck. These calcineurin inhibitors, however, are currently recommended for children older than 2 years of age, and as second-line agents to be used if topical steroid therapy and moisturizers are ineffective. Finally, being alert to the presence of possible secondary infection (especially Staphylococcus aureus) and treating such infection with a course of an effective oral antibiotic or topical mupirocin (if the lesions are more localized) often leads to significant improvement.

Figure 1.4 Atopic dermatitis in the antecubital fossa of an older child. (See color insert.) |

Most easily recognized by its typical pattern of rashes, contact dermatitis is seen in patches, linear arrays, and unusual distributions (Fig. 1.5). Poison ivy (also oak or sumac), also known as Rhus dermatitis, is a paradigm for contact dermatitis. Lines and patches of textured (“orange peel”) erythema soon develop on the skin that has come in contact with the oil of the plant leaves or stem. These rapidly become microvesicular rashes and can progress to larger blisters, which then open and weep. Contact dermatitis is typically pruritic. Treatment involves the following:

Figure 1.5 A child with contact dermatitis of the arm. (See color insert.) |

Oral antihistamine to control itching

Topical steroids (moderate potency)

Consideration of oral steroids (prednisone or prednisolone for 1 week at a dosage of 1 to 2 mg/kg per day, with the dose tapered during the second week to prevent rebound of the rash) if the rash is extensive or involves the genitalia or skin around the eyes, potentially causing eyelid edema

Finally, acrodermatitis enteropathica can be considered in the same general category. This autosomal-recessive disorder causes zinc deficiency, and its clinical presentation is similar to that of nutritional zinc deficiency (as occurs in premature or chronically malnourished infants). In genetically susceptible infants who have been breast-fed, it often presents at the time of weaning, an observation that raises the possibility that a zinc-binding ligand in breast milk enhances zinc absorption up to the time of weaning. The associated rash is moist, erythematous, and papular, forming plaques on the skin around orifices (mouth, nose, ears, and perineum) and on the acral areas (hands and feet) (see Fig. 67.5). Associated systemic symptoms include a foulsmelling, frothy diarrhea; alopecia; irritability or apathy; and a generalized failure to thrive. Abnormal laboratory values include low levels of serum zinc and serum alkaline phosphatase (a zinc-dependent enzyme). Treatment is with zinc sulfate 5 mg/kg per day, which usually brings about a dramatic reversal of the symptoms and rash within several weeks.

PAPULOSQUAMOUS RASHES

Papulosquamous rashes are both raised (“papulo-”) and covered with fine scaling (“-squamous”). Pityriasis rosea (Fig. 1.6) is a rash that may be seen every month or two in a pediatric practice, more commonly in teenagers and older children than in younger patients. The cause is unknown; it may be viral, although the condition is infrequently seen in more than one family member. The initial lesion is a “herald patch,” a 2- to 4-cm scaly round or oval plaque with a raised border. A typical exanthem follows within 5 to 7 days, producing 2- to 10-mm ovoid, slightly raised plaques with central scaling in addition to smaller individual papules. The long axes of the smaller ovoid lesions are parallel to the crease lines of the skin, producing a “Christmas tree” pattern over the back if the rash is well developed. The rash lasts for 6 to 10 weeks and resolves without treatment. Secondary syphilis sometimes mimics pityriasis

rosea, but unlike pityriasis rosea, often includes lesions on the palms and soles.

rosea, but unlike pityriasis rosea, often includes lesions on the palms and soles.

Figure 1.6 Papulosquamous lesions of pityriasis rosea. (See color insert.) |

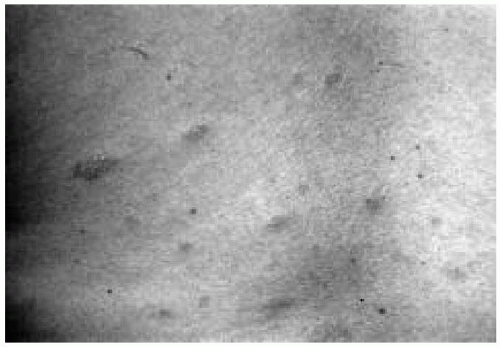

Psoriasis (Fig. 1.7) is an unusual cause of scaly patches in children but must be kept in mind for the differential diagnosis, which includes tinea corporis, seborrhea, and pityriasis rosea. Psoriasis affects as many as 1% to 2% of adults, and approximately 35% of these instances present before the age of 20 years. Approximately 60% of pediatric patients have a first-degree relative with psoriasis. Sometimes precipitating factors can be uncovered, including trauma, cold, stress, and group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection. One form of psoriasis, guttate psoriasis, can develop 2 to 4 weeks after a streptococcal infection, presenting with predominantly small, “drop-like” lesions. Psoriasiform lesions are red-based plaques with a fine, adherent silvery scale; their removal produces pinpoints of bleeding (Auspitz sign). The lesions are found on the knees, elbows, scrotum, and scalp. Nail pitting occurs in about half of clinical cases of psoriasis.

Figure 1.7 Scaly patches of psoriasis in a child. (See color insert.) |

The treatment of psoriasis entails a minimal use of soap and the liberal use of thick emollients, keratolytics (with salicylic or lactic acid), and topical steroids of adequate potency to control inflamed lesions. Calcipotriene (a synthetic vitamin D3 analog) topical cream or ointment has been an efficacious addition to therapy for teenagers and adults. Psoriasis is usually a chronic condition that is often difficult to treat and usually warrants consultation with a dermatologist who treats children.

VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS AND HEMANGIOMAS

Vascular malformations are hamartomas (anomalous morphogenesis) of mature endothelial cells that are present (but not always seen) at birth and enlarge with body growth. The blood flow through these lesions is either normal or slower than normal. Vascular malformations can affect the growth of underlying bone and soft tissue, causing asymmetric overgrowth (Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome). The most common vascular malformation is the “salmon patch” seen on the middle of the forehead, glabella, philtrum, or upper eyelids of about one third of newborns. This dull, reddish lesion becomes quite red when the infant cries, but the parents can be reassured that it will fade by 18 to 24 months of age, except if located on the nape of the neck, in which case it may persist.

Port wine stains are composed of mature, dilated dermal capillaries and are persistent. They range from light to dark red in color, and often deepen to a purplish hue with aging. If the distribution of the port wine stain includes the ophthalmic (upper eyelid to forehead) branch of the trigeminal nerve (see Fig. 35.8), the patient may have Sturge-Weber syndrome (estimated risk 8% to 29%). This syndrome includes ipsilateral leptomeningeal involvement and intracranial calcifications, which may be seen at the earliest with magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography. Seizures develop in 60% to 90% of these patients, and about half of them have mental retardation. Concomitant eye findings in patients with this syndrome in whom the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the trigeminal nerve are involved include glaucoma. It is recommended that port wine stains be treated with the pulsed tunable dye laser, emitted at a wavelength absorbed by hemoglobin in the vessels of the most superficial 1-mm layer of the skin. Multiple treatments are generally required, and the result is often quite good.

Hemangiomas can, by distinction, be considered benign neoplasms of endothelial cells, characterized by rapid

blood flow and an increased density of mast cells within the lesion. They grow rapidly during infancy, then plateau and begin to involute by 18 to 24 months of age. As a rough rule, approximately 50% of hemangiomas resolve by 5 years of age, 70% by 7 years, and 90% by 9 years. The several different types of hemangiomas are classified by morphology. Superficial hemangiomas (formerly called “strawberry” hemangiomas) (Fig. 1.8) are well defined, raised, and light to deep red in color. Deeper (“cavernous”) hemangiomas (Fig. 1.9) involve capillary growth into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue; therefore, they are often soft blue to red in color.

blood flow and an increased density of mast cells within the lesion. They grow rapidly during infancy, then plateau and begin to involute by 18 to 24 months of age. As a rough rule, approximately 50% of hemangiomas resolve by 5 years of age, 70% by 7 years, and 90% by 9 years. The several different types of hemangiomas are classified by morphology. Superficial hemangiomas (formerly called “strawberry” hemangiomas) (Fig. 1.8) are well defined, raised, and light to deep red in color. Deeper (“cavernous”) hemangiomas (Fig. 1.9) involve capillary growth into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue; therefore, they are often soft blue to red in color.

Figure 1.8 A superficial (“strawberry”) hemangioma. (See color insert.) |

Hemangiomas occur in 10% to 12% of children, and at least 90% of them resolve without treatment. Exceptions to the watchful waiting approach are necessary if the growing hemangioma interferes with vision or obstructs the airway; in such cases, active intervention with steroids, interferon, or laser treatment (if superficial) is indicated. Midline lumbar or sacral hemangiomas may be associated with underlying spinal cord involvement and would warrant consideration of imaging of the cord. Hemangiomas involving the lip or breast tissue or those in a segmental pattern may also warrant more active therapy. A particular situation involving a large “hemangioma,” thrombocytopenia, and consumptive coagulopathy is the Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. These lesions are actually not true hemangiomas, but rather tufted angiomas or kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas.

Figure 1.9 A deep or cavernous hemangioma. (See color insert.) |

PIGMENTED AND HYPOPIGMENTED LESIONS

Several dermatologic conditions are associated with hyperpigmentation. Mongolian spots (dermal melanosis) (Fig. 1.10) are commonly observed in children of African-American, Asian, Hispanic, or Mediterranean descent. The dull, blue-black macule is found most commonly over the lower spine, but can be seen anywhere on the body, especially the shoulders and arms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree