CHAPTER 124

Patellar Dislocation

(Kneecap Dislocation)

Presentation

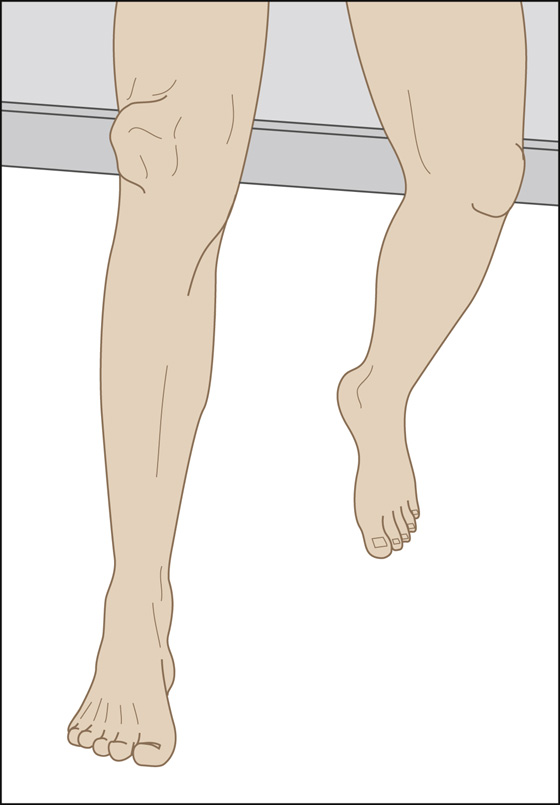

After a direct blow to the medial aspect of the patella or, more commonly, without contact and only after a sudden twisting motion to the opposite side of an outward-pointing planted foot (with a powerful contraction of the quadriceps while the thigh is turning inward), the patient’s kneecap dislocates laterally. The patient, who is usually an adolescent, is brought in with the knee guarded and slightly flexed, in severe pain, with the patella situated lateral to the lateral femoral condyle, creating an obvious lateral deformity (Figure 124-1). Most often, there will have been a spontaneous reduction, and the patient reports that the knee or kneecap “gave way” or “gave out” with pain and then slipped back into place. A patient with recurrent, acute dislocation is usually able to relate an appropriate history and usually knows exactly what happened.

Figure 124-1 Patellar dislocation.

What To Do:

For a persistent dislocation, provide immediate reduction. Pain medications and sedatives may be needed for reduction, but gaining the patient’s confidence while holding and stabilizing the leg will minimize this need. Position the patient with a slight flexion of the hip to reduce strain on the quadriceps muscle (one way to do this is to have the patient sitting on the edge of the stretcher with legs down). Stand on the lateral side of the patient (for a medial dislocation, stand on the medial side of the patient). Slowly and gently extend the lower leg at the knee while holding the patella in place until the knee is fully extended. If needed, apply continuous gentle anteromedial force to the patella to lift it over the edge of the femoral condyle. Once reduced, apply a knee immobilizer and fit the patient with crutches.

For a persistent dislocation, provide immediate reduction. Pain medications and sedatives may be needed for reduction, but gaining the patient’s confidence while holding and stabilizing the leg will minimize this need. Position the patient with a slight flexion of the hip to reduce strain on the quadriceps muscle (one way to do this is to have the patient sitting on the edge of the stretcher with legs down). Stand on the lateral side of the patient (for a medial dislocation, stand on the medial side of the patient). Slowly and gently extend the lower leg at the knee while holding the patella in place until the knee is fully extended. If needed, apply continuous gentle anteromedial force to the patella to lift it over the edge of the femoral condyle. Once reduced, apply a knee immobilizer and fit the patient with crutches.

Some practitioners have had luck with the following maneuver as well: gain the patient’s confidence and cooperation while gently grasping the patella and stabilizing it by applying mild lateral traction and maintaining its position to prevent sudden motion. Place the patient in the semiprone position for relaxation. Then have the patient allow you to passively and very gradually extend the knee. When it is fully extended, slowly release traction on the patella while maintaining continuous control and gently let it slip into its normal anatomic position (medial force is generally not required). With experience, this technique rarely requires any analgesia or sedation, only a calm and reassuring approach.

Some practitioners have had luck with the following maneuver as well: gain the patient’s confidence and cooperation while gently grasping the patella and stabilizing it by applying mild lateral traction and maintaining its position to prevent sudden motion. Place the patient in the semiprone position for relaxation. Then have the patient allow you to passively and very gradually extend the knee. When it is fully extended, slowly release traction on the patella while maintaining continuous control and gently let it slip into its normal anatomic position (medial force is generally not required). With experience, this technique rarely requires any analgesia or sedation, only a calm and reassuring approach.

After the patella has been reduced and the patient is comfortable, order knee radiographs, including patellar views, to rule out an avulsion fracture of the superomedial pole of the patella, an osteochondral fracture of the lateral femoral condyle, or a fracture of the medial posterior patellar articular surface. There are associated fractures in 28% to 50% of patellar dislocations, which can lead to degenerative arthritis. It must be appreciated that plain radiographs do not show a high percentage of osteochondral fractures occurring at the time of patellofemoral dislocation.

After the patella has been reduced and the patient is comfortable, order knee radiographs, including patellar views, to rule out an avulsion fracture of the superomedial pole of the patella, an osteochondral fracture of the lateral femoral condyle, or a fracture of the medial posterior patellar articular surface. There are associated fractures in 28% to 50% of patellar dislocations, which can lead to degenerative arthritis. It must be appreciated that plain radiographs do not show a high percentage of osteochondral fractures occurring at the time of patellofemoral dislocation.

If pain persists beyond early rehabilitation, new articular cartilage MRI techniques should be used to identify any undiagnosed osteochondral injuries. MRI also has a role in determining the extent and location of injury to the medial patellofemoral ligament.

If pain persists beyond early rehabilitation, new articular cartilage MRI techniques should be used to identify any undiagnosed osteochondral injuries. MRI also has a role in determining the extent and location of injury to the medial patellofemoral ligament.

A standard evaluation of the knee ligaments should be performed to rule out concurrent injury (see Chapter 115).

A standard evaluation of the knee ligaments should be performed to rule out concurrent injury (see Chapter 115).

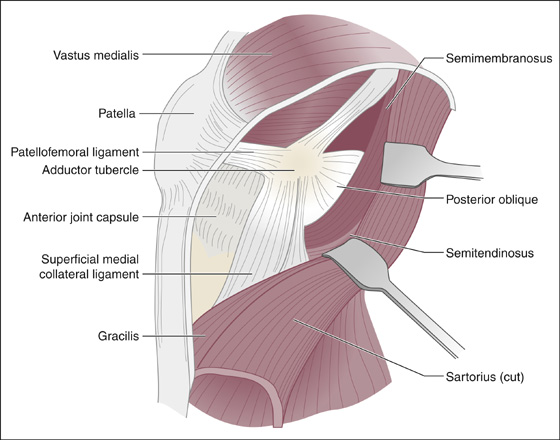

Palpate for rents in the vastus medialis obliquus and the medial patellofemoral ligament or for a grossly dislocatable patella (Figure 124-2). Also note the presence of any swelling or effusion.

Palpate for rents in the vastus medialis obliquus and the medial patellofemoral ligament or for a grossly dislocatable patella (Figure 124-2). Also note the presence of any swelling or effusion.

Figure 124-2 Anatomic structures of the medial patellofemoral ligament and the vastus medialis obliquus and patella.

A hemarthrosis can develop from a capsular tear and/or an osteochondral fracture. Some authors suggest that when a tense and painful hemarthrosis is present, aspiration should be considered to reduce pain and check for fat droplets, indicating an occult osteochondral injury.

A hemarthrosis can develop from a capsular tear and/or an osteochondral fracture. Some authors suggest that when a tense and painful hemarthrosis is present, aspiration should be considered to reduce pain and check for fat droplets, indicating an occult osteochondral injury.

Fit the patient for crutches and a knee immobilizer that will keep the knee straight.

Fit the patient for crutches and a knee immobilizer that will keep the knee straight.

Provide analgesia as required, and instruct on the use of ice and elevation. Teach non–weight-bearing walking with crutches.

Provide analgesia as required, and instruct on the use of ice and elevation. Teach non–weight-bearing walking with crutches.

Provide orthopedic follow-up in 1 to 3 days.

Provide orthopedic follow-up in 1 to 3 days.

Quadriceps isometrics, straight-leg raises, and single-plane motion exercises are begun early and progress as tolerated. Quadriceps strengthening is paramount and kept in balance with adequate extensor mechanism rehabilitation. Repetition of the injury mechanism or mechanically similar activities must be avoided in the healing period. Exercises should be done in a pain-free manner. Patellar pain may indicate unrecognized or progressive articular cartilage damage. As strength and symptoms allow, patients progress out of their brace in physical therapy to single plane walking, running, cutting, and finally sport-specific activity.

Quadriceps isometrics, straight-leg raises, and single-plane motion exercises are begun early and progress as tolerated. Quadriceps strengthening is paramount and kept in balance with adequate extensor mechanism rehabilitation. Repetition of the injury mechanism or mechanically similar activities must be avoided in the healing period. Exercises should be done in a pain-free manner. Patellar pain may indicate unrecognized or progressive articular cartilage damage. As strength and symptoms allow, patients progress out of their brace in physical therapy to single plane walking, running, cutting, and finally sport-specific activity.

What Not To Do:

Do not try to force the patella to move medially. This may succeed in reduction but is unnecessarily painful and can cause harm.

Do not try to force the patella to move medially. This may succeed in reduction but is unnecessarily painful and can cause harm.

Discussion

The patella is the largest sesamoid bone in the body, and it resides within the complex of the quadriceps and patellar tendons. It functions as both a lever and a pulley. As a lever, the patella magnifies the force exerted by the quadriceps on knee extension. As a pulley, the patella redirects the quadriceps force as it undergoes normal lateral tracking during flexion.

Most series on patellar dislocation report a greater incidence in women, although some series have reported equal numbers of men and women affected, and others have found a higher incidence in men. Depending on the study, 30% to 72% of dislocations can be expected to be sports related, and 28% to 39% will have associated osteochondral fractures. Concurrent osteochondral injuries are a major contributor to adverse outcomes.

The most common sports involved are football, basketball, and baseball, but it is not unusual in gymnastics, simple falls, cheerleading, and dancing. This injury may occur when patients with normal anatomy are exposed to direct high-energy forces, but most studies find that it occurs more commonly when patients with abnormal anatomy are exposed to indirect forces. Some authors think that anatomic predispositions, such as patella alta, trochlear dysplasia, and ligamentous laxity, play greater roles in recurrent instability.

The average age of these patients is 16 to 20 years old; it is a rare injury for those older than age 30. The incidence of recurrent dislocation decreases with age. Fourteen-year-olds have a 60% incidence of redislocation, whereas 17- to 28-year-olds have an incidence of 30%.

Most patellar dislocations are of the lateral type. Horizontal, superior, and intracondylar patellar dislocations are very uncommon and usually require surgical reduction.

Relative indications for early operative intervention after an acute lateral patella dislocation are controversial, without clear supporting research, but include the following: (1) failure to improve with initial nonoperative care, (2) concurrent osteochondral injury, (3) continued gross patella instability, (4) palpable disruption of the medial patellofemoral ligament–vastus medialis obliquus–adductor mechanism, and (5) high-level athletic demands coupled with mechanical risk factors and an initial injury mechanism not related to contact.

One study suggests that most patients without anatomic abnormality do well whether they are treated conservatively or surgically, and that among patients with anatomic abnormality, half will do well if treated conservatively, whereas up to 80% will do well if treated surgically. Some studies show a trend toward increased osteoarthritis following surgical repair for patella dislocation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree