Key Clinical Questions

When should a patient with an erythematous scaly eruption be evaluated for an underlying infectious process?

How should the patient with diffuse erythroderma be evaluated?

What are the best topical treatments for psoriasis?

Are oral steroids useful in the treatment of psoriasis?

Are there physical findings that help differentiate between contact and irritant dermatitis?

Introduction

Papulosquamous disorders are a group of unrelated dermatologic conditions in which patients present with red, raised lesions with scale. While psoriasis is the prototypical papulosquamous disorder, similar skin lesions are seen in infections, lymphomas, and allergic conditions. The conditions described in this chapter are ubiquitous, and primarily inflammatory in nature. From a clinical point of view, the history, the distribution of the lesions, and careful evaluation of the primary lesion are most helpful in helping establish the diagnosis. Ancillary tests include a KOH preparation, a skin biopsy and, if necessary, dermatologic consultation. It should be remembered that treating a condition without a definitive diagnosis can lead to unnecessary patient aggravation and added expense.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis, a chronic relapsing condition with genetic and environmental triggers, can be readily diagnosed on skin examination. It is very common. Approximately 2% of the population is affected by psoriasis. In the United States, the prevalence may be as high as 4.6%.

Psoriasis was formerly likened to “wound healing gone wrong.” It was blamed on abnormally rapid keratinocyte growth and maturation, with a reduction of the epidermal turnover time from the normal 4 weeks to only 3 to 4 days. However, psoriasis is now recognized to be a T-cell–mediated disease. Several Th-1 helper lymphocyte-associated cytokines drive epidermal proliferation, such as interferon-α, tumor necrosis factor, and certain interleukins. Circulating levels of IL-22 are especially correlated with disease activity. Biopsy reveals epidermal hyperplasia with tortuous papillary dermal blood vessels, and a loss of the granular layer with abundant parakeratotic scale. In pustular lesions, neutrophils form collections in the epidermis.

The lesions are well demarcated and associated with a characteristic silvery white, plate-like adherent scale (Figure 143-1).

When the thick scale is forcibly removed, small punctate bleeding points develop (the Auspitz sign) (Figure 143-2).

Psoriasis may affect the entire body surface, including the nails. As injury can trigger psoriasis, lesions are typically seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks (Figure 143-3).

While some patients are only troubled by pruritus, most are ashamed of their appearance and the unsightly scaling. Variants include the chronic plaque type, guttate psoriasis, and pustular psoriasis, all of which can evolve into the erythrodermic variant.

In plaque-type psoriasis, the most common presentation, patients develop well-demarcated erythematous scaly plaques distributed symmetrically over the extremities, often involving both elbows and knees. Psoriasis of the gluteal cleft is also common (Figure 143-4).

The lesions are chronic and persistent. In the guttate variant, which usually involves a younger age group, the lesions develop acutely, are smaller, have less scale, and are distributed widely over the trunk and buttocks (Figure 143-5).

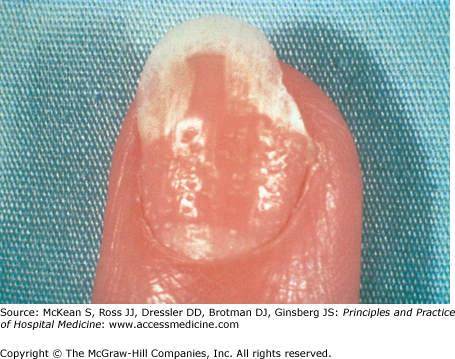

This variant is often triggered by an antecedent upper respiratory infection. In the rarer pustular variant, numerous pustules can be seen in a limited distribution involving acral sites (pustulosis of the palms and soles) or in a more generalized distribution associated with diffuse erythema (von Zumbusch variant). Common nail changes in psoriasis include nail pitting (Figure 143-6), onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), and subungual hyperkeratosis.

Occasionally a yellow shiny lesion, or “oil spot,” develops in the nail bed. About 10% of patients have concomitant arthritis, which may be severe.

In a patient with a few isolated, red, raised lesions, tinea corporis, atopic dermatitis, contact and irritant dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma should be considered. In tinea corporis the lesions are more annular with central clearing and have a raised border, often with only fine peripheral scale. A KOH preparation of the scale demonstrating fungal hyphae is diagnostic. In atopic, contact, and irritant dermatitides, the lesions are not so well demarcated and the distribution is different. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma often presents on the buttocks and posterior thighs, but the plaques are thin and somewhat less red. A skin biopsy revealing atypical T lymphocytes within the epidermis is helpful in confirming this diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of the guttate variant includes drug eruption, viral exanthem, secondary syphilis, and pityriasis rosea. In the pustular variant involving the palms and soles, infections and impetiginized dyshidrotic eczema are in the differential diagnosis. In the more generalized pustular variant of psoriasis, pustular drug eruption and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) should be excluded.

In the hospitalized patient with chronic plaque-type psoriasis, it is reasonable to continue the patient’s outpatient regimen. Topical steroid creams and ointments containing the vitamin D derivative calcipotriol or the retinoid tazarotene are mainstays of treatment. Both modify epidermal proliferation. Anthralins and tars are also effective, but not as widely used. Patients with a few lesions of the guttate variant may be treated with topical steroids alone. However, underlying streptococcal pharyngitis should be excluded, and treated if present. Systemic high-dose corticosteroids should be used with great caution in patients with psoriasis, as a severe flare of psoriasis with total body erythroderma may occur as glucocorticoids are tapered.

In patients with more generalized lesions of the chronic type and the guttate variant, which often involve 20% of the body or more, therapeutic options include ultraviolet (UV) therapy with narrow or broadband UVB, or psolaren UVA therapy, combining oral methoxy-psoralen with UVA radiation. The guttate variant usually resolves spontaneously over three months, but phototherapy hastens resolution. Additional therapies for diffuse recalcitrant psoriasis include acitretin, cyclosporine and methotrexate. Newer biologic agents, targeting either specific cytokines or specific T-cells, should be used in consultation with a dermatologist.

Erythroderma

Erythroderma, or exfoliative dermatitis, refers to extensive body redness often associated with scale. Diffuse erythroderma may be produced by several different underlying skin conditions. In 25% of cases, no clear cause is found. Erythroderma is rare, with a reported incidence of 1 to 2 per 100,000 of the population. Men are more often affected. The mean age of onset is 60 years.