PANCREATIC INJURY

CASE SCENARIO

A 45-year-old man with no significant past medical history was a restrained driver in a motor vehicle collision. Paramedics report significant damage to the vehicle, including a deformed steering wheel, with no airbag deployment. He is hemodynamically appropriate on arrival in the emergency room, but complains of epigastric pain.

On primary survey, his airway is patent, his breath sounds are equal bilaterally, and pulses are easily palpable and symmetric. His physical examination is significant for abdominal tenderness in the bilateral upper quadrants. His abdomen is otherwise soft with no guarding or rebound. His extremities are warm without any obvious deformities.

A portable chest x-ray is within normal limits. A focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination shows no free fluid in the abdomen. Lab work reveals an elevated white blood cell count of 13, normal hematocrit, normal coagulation profile, and an elevated serum amylase at 160.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Pancreatic injury has been reported in 1% to 5% of all cases of blunt abdominal trauma and up to 12% of penetrating trauma.1–4 Common mechanisms include motor vehicle collisions with or without seatbelt use, bicycle “over the handlebars” accidents, assaults, and gunshot and stab wounds. Likely due to its retroperitoneal location (see the below), isolated pancreatic trauma is rare, and other intra-abdominal injuries are found in >90% of cases.5 The organs most commonly injured concurrently include the liver, spleen, duodenum, and small intestine.

Although relatively uncommon, pancreatic injuries are associated with a high mortality (10%–30%) and morbidity (30%–60%).6 Early mortality in these patients is often secondary to hemorrhage, while later mortalities are frequently due to infection, associated injuries, and sequelae of pancreatic leaks. A delay in diagnosis of >24 hours has been associated with a threefold increase in mortality.7

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

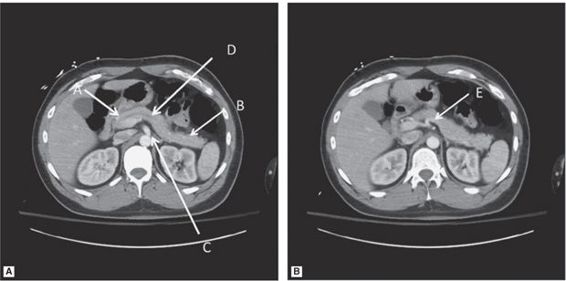

The pancreas is a retroperitoneal organ with both exocrine and endocrine functions. It is divided into five parts including the head, uncinate process, neck, body, and tail (Figure 27–1). The pancreatic head sits in the curve of the duodenum to the right of midline at the level of the second lumbar vertebral body. The neck separates the head from the body and is anterior to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the confluence of the portal vein (PV) with the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and the splenic vein. The body of the pancreas is anterior to the aorta and directly in front the first lumbar vertebra (L1), a position that makes it particularly vulnerable to blunt abdominal trauma. The body crosses the midline and merges without a discernible junction with the pancreatic tail, which extends to the hilum of the spleen. Although ductal anatomy can vary, the main pancreatic duct of Wirsung runs the length of the pancreas. The accessory duct of Santorini usually branches from the pancreatic duct and empties separately into the duodenum. Arterial supply to the head and neck is derived from the celiac axis via the superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries, and from the SMA via the inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries. The splenic artery (a branch of the celiac artery) supplies blood to the body and tail of the pancreas via numerous side branches. Venous drainage follows the arteries.

Figure 27–1 Normal pancreas. Pancreatic head (arrow A), pancreatic tail (arrow B), origin of superior mesenteric artery (arrow C), main pancreatic duct (arrow D), splenic artery (arrow E). Note the proximity of the pancreas to other organs including duodenum, inferior vena cava, bilateral kidneys, spleen, and aorta.

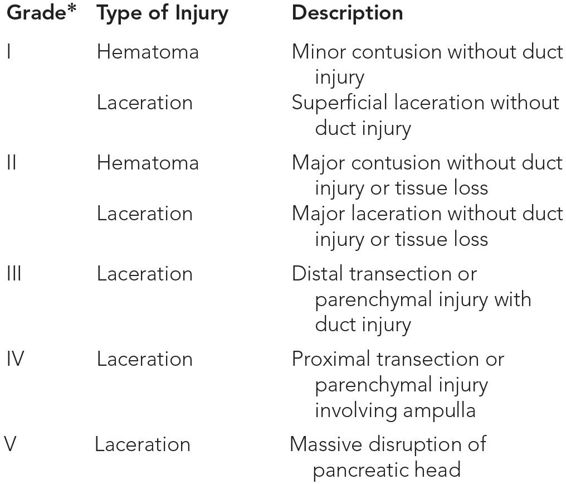

Injury to the pancreas can occur from either blunt or penetrating trauma. Blunt injury to the pancreas typically occurs from compression of the fixed retroperitoneal pancreas between the vertebral column and the anterior abdominal wall, with two-thirds of pancreatic injuries occurring in the pancreatic body. Injuries can range from mild pancreatic contusions with parenchymal edema and swelling, with or without hematoma formation, to pancreatic transection and major hemorrhage. A widely utilized grading scale is the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Pancreas Injury Scale (Table 27–1). The presence of a duct injury and its location (proximal vs distal) are key determining factors in management strategies as well as outcomes.

*Multiple injuries: advance grade by one until grade III.

Complications of pancreatic injuries include pancreatic fistula, pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreatitis, and intraabdominal abscesses. In addition, due to the pancreas’s proximity to a number of other organs and main blood vessels, associated injuries and hemorrhage contribute to the morbidity and mortality.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of patients with pancreatic injury is often nonspecific and may depend on the associated injuries. Patients may be hemodynamically normal, unstable, or even in extremis. Initially, patients with isolated pancreatic injury may manifest only subtle or no signs due to the retroperitoneal location of the pancreas.

Physical examination may include abdominal pain and tenderness that ranges from subtle discomfort to overt peritonitis. A seatbelt sign or Grey-Turner’s sign of flank ecchymosis suggests a pancreas or spleen injury in the setting of blunt abdominal trauma. However, abdominal findings may be overshadowed by symptoms related to cranial, truncal, or extremity injuries. The unreliable patient who is intubated, intoxicated, or has a head injury also presents a diagnostic challenge. A trauma mechanism consistent with possible pancreatic injury therefore warrants a high index of suspicion, and appropriate imaging is crucial.

Although the initial blood work in multisystem trauma patients often includes an amylase or lipase level, a single result has not been proven to be sufficiently sensitive or specific. An increasing or persistently elevated level, however, requires further evaluation.

Delayed presentation of a pancreatic injury may include persistent or progressing abdominal pain, shock, fever, leukocytosis, and sepsis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Following trauma, the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain is broad and includes injury to any intra-abdominal structure, including other solid organs such as liver and spleen, the gastrointestinal tract, bowel or bladder, as well as soft tissue contusions to the abdominal wall (Table 27–2).