(1)

Trauma and Critical Care, R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, Baltimore, MD, USA

Keywords

PancreasDuodenumBlunt injuryPenetrating injuryREBOA catheterCentral retroperitoneal hematomaRetroperitoneal bile stainingPeritoneal fat saponificationPeritoneal fat necrosisPancreatic edemaLesser sac edemaEndoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)CholecystocholangiopancreatographyPancreatectomyResectionNasogastric decompressionIntravenous hydrationParenteral nutritionInterrupted Lembert suturesPrimary repairPyloric exclusionWhipple procedureIntroduction

Eat when you can, sleep when you can, and don’t mess with the pancreas.Surgical Dictum

The pancreas and the duodenum are retroperitoneal organs intimately associated with one another and deeply positioned in the mid-abdomen. Isolated injuries are infrequent from either blunt or penetrating mechanisms as these organs are surrounded by numerous other vital structures (Tables 13.1 and 13.2) [1]. Early mortality is high due to associated injuries to the vascular or central nervous systems, but delays in diagnosis and complications in the treatment of pancreatic and duodenal injuries contribute to later deaths from sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction. Even in tertiary trauma centers, these injuries are rare. Consequently, surgeons generally possess limited, first-hand experience in operative care and overall management. A query of the Shock Trauma Center Registry for the inclusive period between January 2000 and September 2013 identified only 466 pancreatic and/or duodenal injuries (34/year) from a total of 68,053 trauma admissions.

Table 13.1

Associated injuries in 1,086 cases of pancreatic trauma.

Associated organ injury | Patients (%) (total 1,086) |

|---|---|

Liver | 500 (46) |

Stomach | 449 (41) |

Major vascular | 300 (28) |

Spleen | 277 (26) |

Kidney | 240 (22) |

Colon | 189 (17) |

Duodenum | 173 (16) |

Small bowel | 165 (15) |

Gallbladder/biliary tree | 46 (4) |

Table 13.2

Associated injuries in 1,234 cases of duodenal trauma.

Associated organ injury | Patients (%) (total 1,234) |

|---|---|

Major vascular | 596 (48) |

Liver | 543 (44) |

Colon | 378 (31) |

Pancreas | 368 (30) |

Small bowel | 363 (29) |

Stomach | 279 (23) |

Kidney | 237 (19) |

Gallbladder/biliary tree | 176 (14) |

Spleen | 41 (3) |

History of Care

Wounds of the pancreas are to be concluded mortal if its duct or blood vessels are injured, whence the succus pancreaticus or blood may be discharged into the cavity of the abdomen, and there putrefying, cause inevitable death. Benjamin Gooch (Collected Works, 1792) [2]

Routinely cited as the earliest report of pancreatic trauma, Travers in 1827 described in The Lancet the case of an intoxicated woman struck by a stage coach who survived for several hours after the incident [3]. “The pancreas, on [postmortem] examination of the body, was found to be completely torn through transversely” [3].

Prior to the 1900s, injuries to the pancreas and duodenum were fatal. In 1903, Mickulicz-Radicki summarized the collective medical experience on pancreatic trauma after identifying 45 published cases: 21 penetrating and 24 blunt injuries [4]. All 20 patients managed nonoperatively died, but only 7 of 25 patients (28 %) treated operatively died. From more than 100 years ago, Mickulicz’s recommendations for the management of suspected pancreatic injuries endure as surgical principles today: (1) thorough abdominal exploration through a midline abdominal incision, (2) suture control of bleeding, and (3) drain placement.

The first successful surgical repair of a blunt duodenal injury is attributed to Herczel in 1896 and of a penetrating duodenal injury to Moynihan in 1901. In 1946, Cave reported on 118 duodenal injuries sustained by the US Army during combat operations during 1944 and 1945 [5]. Ten-day mortality in this cohort was 55.9 % in an era that predates antibiotic therapy. In 1977, Vaughan et al. reported on their institution’s 7-year experience utilizing pyloric exclusion and gastrojejunostomy for duodenal trauma, and this procedure currently remains a frequent adjunct in the management of severe injuries [6].

Operative Technique

Surgical Anatomy

The pancreas measures approximately 20 cm long, 3 cm wide, and 1.5 cm thick and lies transversely across the upper abdomen in the retroperitoneum (Fig. 13.1). It is divided into four anatomic sections: the head lies to the right of the midline and is nestled within the C-loop of the duodenum, the neck overlies the superior mesenteric artery and vein in the midline, the body continues laterally to the left, and the tail ends in proximity of the spleen anterior to the left kidney (Fig. 13.2). The uncinate process is a small extension of the head that is nestled behind the superior mesenteric vessels. The splenic artery courses along the upper posterior border of the pancreas. Behind the pancreas, the splenic vein travels close to its lower border and is joined by both the inferior and superior mesenteric veins to form the portal vein. Also posterior to the pancreas lie the aorta, the inferior vena cava, the left kidney, both renal arteries, and the left renal vein. The stomach and root of the transverse mesocolon overlie the pancreas.

Fig. 13.1

Anatomy of the upper abdomen. Gray’s Anatomy, Fig. 1056. 1918.

Fig. 13.2

Anatomy of the pancreas. Reprinted with permission from Bulger EM, Jurkovich GJ. Operative management of pancreatic trauma. Oper Tech Gen Surg 2000;2(3):221–33.

The duodenum extends from the gastric pylorus to the ligament of Treitz and measures approximately 30 cm in length. The duodenum is similarly divided into four anatomic sections: superior (D1), descending (D2), transverse (D3), and ascending (D4) (Fig. 13.2). The transition from D1 to D2 occurs as the duodenum crosses the common bile duct and the gastroduodenal artery, from D2 to D3 occurs at the ampulla of Vater, and from D3 to D4 occurs as the superior mesenteric vessels cross anteriorly over the duodenum. The aorta, inferior vena cava, right kidney, spinal vertebrae, and psoas muscles lie posterior to the duodenum. The liver, gallbladder, right colon, transverse colon, and stomach overlie the duodenum.

The blood supply of the pancreas and duodenum arises from arcades originating from the gastroduodenal, superior mesenteric, and splenic arteries. Variations in the arterial and the pancreatic/biliary ductal anatomy exist.

Damage-Control Management of Pancreatic and Duodenal Injuries

If hemodynamic instability necessitates urgent abdominal exploration, the highest priority is rapid control of bleeding. An abundance of vascular structures surrounds the pancreas and duodenum so that exsanguinating hemorrhage is a common cause of early mortality. A generous midline laparotomy incision is used. Continued bleeding from the midline structures may necessitate total occlusion of aortic inflow by clamping the supraceliac aorta. More recently, empiric placement of a REBOA (resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta) catheter via a femoral artery cutdown may be considered in select patients [7]. Preoperative placement allows for rapid aortic occlusion by balloon inflation only should aortic occlusion prove to be necessary [8]. Rapid division of the pancreatic neck with a surgical stapler may be required to expose bleeding vessels such as the superior mesenteric vein located behind the pancreas for direct surgical control.

After control of hemorrhage, minimizing bacterial contamination is the next priority. Injuries are rapidly managed by either gross suture closure or stapling with or without resection. This is not the time for pancreatic or duodenal reconstructions, and wide drainage is the acceptable bailout maneuver. Once hemorrhage and contamination are controlled, a temporary abdominal dressing is placed and continued aggressive resuscitation undertaken to correct acidosis, coagulopathy, and hypothermia. Due to the nature of their digestive secretions, delays in management of pancreaticoduodenal injuries with suboptimal initial drainage will contribute to increased morbidity and mortality. A second-look operation should be performed as promptly as the patient’s physiology allows.

Exploration of the Pancreas and Duodenum

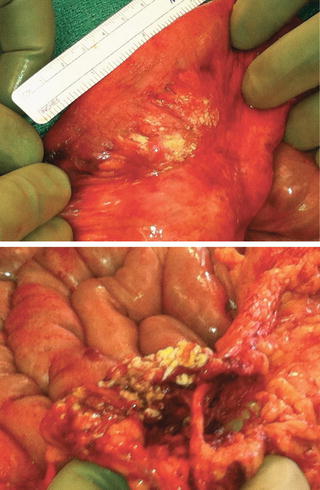

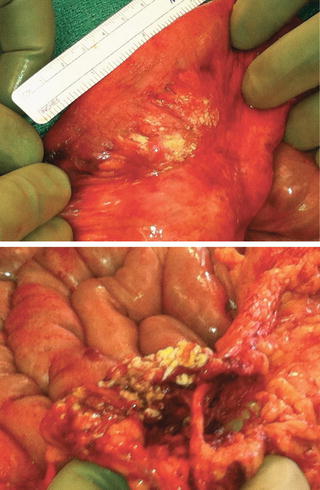

Thorough evaluation of the pancreas and duodenum is mandatory if there is any suspicion of injury from the mechanism of injury, computed tomography (CT) imaging results, trajectory of penetrating wounds, or intraoperative findings. Suggestive operative findings at initial or second-look abdominal exploration include central retroperitoneal hematoma, retroperitoneal bile staining, peritoneal fat saponification or necrosis, and pancreatic and lesser sac edema (Fig. 13.3).

Fig. 13.3

Fat saponification discovered on abdominal exploration suggests possible pancreatic injury.

Good exposure is the key to good surgery.Surgical Dictum

Adequate exposure is crucial to investigate for pancreaticoduodenal injury (Fig. 13.4). The anterior surface of the pancreas is visualized by widely opening the lesser sac between the stomach and the transverse colon through the gastrocolic ligament. A curved, handheld Sweetheart (also known as Harrington) retractor that retracts the stomach cephalad facilitates exposure. Mobilization of the inferior border of the pancreas and cephalad rotation then exposes the posterior surfaces of the body and tail. (The splenic artery courses along the superior border and distributes branches to the pancreas making mobilization of this border perilous.) The pancreatic tail can be mobilized with the spleen from the left upper quadrant to the midline by blunt dissection of an avascular posterior plane between the pancreas and the left kidney. Following mobilization of the hepatic flexure and proximal transverse colon, the Kocher maneuver mobilizes the duodenum and pancreatic head to the midline. This allows inspection of the anterior and posterior surfaces of the duodenum as well as the pancreatic head and neck.

Fig. 13.4

Surgical exposure of the pancreas and duodenum. (a) Exposure of the head of the pancreas and duodenum is obtained via a generous Kocher maneuver. (b) Exposure of the body and tail of the pancreas by entry into the lesser sac. (c) Complete exposure of the tail of the pancreas requires lateral to medial splenic mobilization. Reprinted from Brown T. Chapter 9, Pancreatic and duodenal injuries (Sleep when you can…). In: Martin MJ, Beekley AC (eds). Front Line Surgery. New York: Springer 2011, p. 115–28.

Management of Pancreatic Injuries

Integrity of the main pancreatic duct is the most important determinant of outcome specific to the pancreatic injury itself. Intraoperative inspection of the pancreas is adequate in most cases to assess whether the duct remains intact. Secretin, 1 unit/kg, can be administered intravenously to facilitate visual identification of a pancreatic duct leak [9]. Ductal integrity may be confirmed by postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or postoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Intraoperative needle cholecystocholangiopancreatography may be attempted although is often not successful [10].

Intraoperative cholecystocholangiopancreatography:

1.

Place a 3-0 silk purse-string suture onto the gallbladder fundus.

2.

Cannulate the gallbladder fundus with a 16- or an 18-gauge angiocatheter (Fig. 13.5).

Fig. 13.5

Intraoperative cholecystocholangiopancreatography. Reprinted with permission from Bulger EM, Jurkovich GJ. Operative management of pancreatic trauma. Oper Tech Gen Surg 2000;2:221–33.

3.

Clamp the common hepatic duct with an atraumatic clamp.

4.

Inject 30–75 mL of water-soluble contrast under fluoroscopic imaging.

Management closely follows the injury severity as classified by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Organ Injury Scale (OIS) (Table 13.3) [11, 12]. A Western Trauma Association management algorithm for the management of pancreatic injuries was published in 2013 [13] (Fig. 13.6). In all pancreatic injuries, placement of an enteral feeding tube distal to the ampulla should be strongly considered prior to abdominal closure. This may be via a nasoenteral feeding tube for lower-grade injuries or by a feeding jejunostomy or gastrojejunostomy tube in higher-grade injuries.

Table 13.3

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale—pancreas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree