Which children need care?

Fortunately, deaths in childhood that can be anticipated and for which palliative care can be planned are rare. A report by ACT (Association for Children with Life Threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families) and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health has recently been updated and offers the currently available information about epidemiology. It suggests that the number of children who would benefit from palliative care is higher than was previously thought.

Palliative care for children is offered for a wide range of life limiting conditions, which differ from adult diseases. Many of these are rare and familial. The diagnosis influences the type of care that a child and family will need, and four broad groups have been identified.

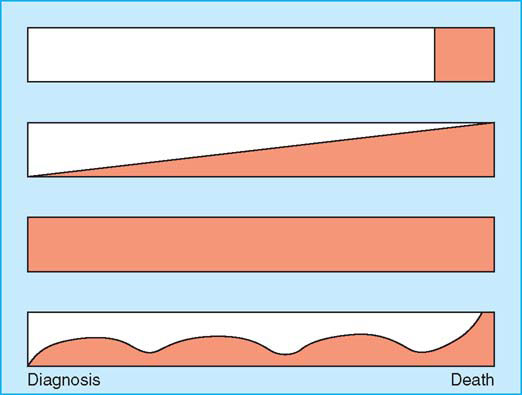

Palliative care may be needed from infancy and for many years for some children, while others may not need it until they are older and only for a short time. Also the transition from aggressive treatments aimed at curing the condition or prolonging good quality life to palliative care may not be clear. Both approaches may be needed in conjunction, each becoming dominant at different times.

Aspects of care in children

Child development

Childhood is a time of continuing physical, emotional, and cognitive development. This influences all aspects of the care of children, from pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of drugs to the communication skills of the children and their understanding of their disease and death.

Care at home

Most children with a life limiting disease are cared for at home. Parents are at the same time part of the team caring for the sick child and part of the family, needing care themselves. As their child’s primary carers, they must be included fully in the care team—provided with information, able to negotiate treatment plans, taught appropriate skills, and assured that advice and support is accessible 24 hours a day.

Assessing symptoms

Assessing symptoms is an essential step in developing a plan of management. Often a picture must be built up through discussion with the child, if possible, combined with careful observations by parents and staff. It is also important to consider the contribution of psychological and social factors for a child and family and to inquire about their coping strategies, relevant past experiences, and their levels of anxiety and emotional distress. There are formal assessment tools for assessing severity of pain in children that are appropriate for different ages and developmental levels, but assessment is more difficult for other symptoms and for preverbal and developmentally delayed children.

Annual mortality from life limiting illnesses

- 1.5–1.9 per 10 000 children aged 1–19 years

- Prevalence of life limiting illnesses

- 12 per 10 000 children aged 0–19 years In a health district of 250 000 people, with a child population of about 50 000 in one year:

- Eight children are likely to die from a life limiting illness–three from cancer, two from heart disease, three others

- 60–85 children are likely to have a life limiting illness, about half of whom will need active palliative care at any time

| Group | Examples |

| Diseases for which curative treatment may be feasible but may fail | Cancer |

| Diseases in which premature death is inevitable but where intensive treatment may prolong good quality life | Cystic fibrosis HIV/AIDS |

| Progressive diseases for which treatment is exclusively palliative and may extend over many years | Batten disease Mucopolysaccharidoses |

| Irreversible but non-progressive conditions leading to vulnerability and health complications likely to cause premature death | Severe cerebral palsy |

Palliative care (shaded) and treatments aiming to cure or prolong life (not shaded) vary in different situations and with time

| • Body charts | • Diaries |

| • Faces scales | • Colour tools |

| • Numeric scales | • Visual analogue scales |

Managing symptoms

In all situations the management plan should consider both pharmacological and psychological approaches along with practical help.

Children often find it difficult to take large amounts of drugs, and complex regimens may not be possible. Doses should be calculated according to a child’s weight. Oral drugs should be used if possible, and children should be offered the choice between tablets, whole or crushed, and liquids. Long acting transdermal and buccal preparations can be helpful, reducing the number of tablets needed and simplifying care at home. Some children find rectal drugs acceptable; they can be particularly useful in the last few days of life. Otherwise, a subcutaneous infusion can be established or, if one is in situ, a central intravenous line can be used. Parents are usually willing and able to learn to refill and load syringes and even to resite needles.

Specific problems

Pain

The myths perpetuating the undertreatment of pain in children have now been rejected. Most doctors, however, lack experience in using strong opioids in children, which often results in excessive caution. Also the difficulties of assessing pain, especially in preverbal and developmentally delayed children, can still result in lack of recognition and undertreatment of pain. After identifying the source of pain in a child appropriate analgesics and non-pharmacological approaches to pain management can be chosen. The WHO’s three step ladder of analgesia is equally relevant for children, with paracetamol, codeine, and morphine forming the standard steps.

Opioids—Laxatives need to be prescribed regularly with opioids, but children rarely need antiemetics. With opioids, itching in the first few days is quite common and usually responds to antihistamines if necessary. Many children are sleepy initially, and parents should be warned of this lest they fear that their child’s disease has suddenly progressed. Respiratory depression with strong opioids used in standard doses is not a problem in children over 1 year, but in younger children starting doses should be reduced.

Adjuvant analgesics—Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are often helpful for musculoskeletal pain in children with non-malignant disease. Caution is needed in children with cancer and infiltration of the bone marrow because of an increased risk of bleeding. Neuropathic pain may be helped by antiepileptic and antidepressant drugs. Pain from muscle spasms can be a major problem for children with neurodegenerative diseases and may be helped by benzodiazepines and baclofen.

Headaches from raised intracranial pressure associated with brain tumours are best managed with analgesic drugs used as described in the WHO guidelines. Although corticosteroids are often helpful initially, the symptoms soon recur and increasing doses are needed. The considerable side effects of corticosteroids in children—rapid weight gain, changed body image, and mood swings—usually outweigh the benefits. Headaches from leukaemic deposits in the central nervous system respond well to intrathecal methotrexate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree