Chapter 8 Pain management and cognitive behavioural therapy

Introduction

Cognitive behavioural interventions are psychologically based therapies that aim to reduce distress. In the context of health conditions such as chronic pain these interventions enable people to develop psychological and physical strategies that help them to manage the condition and its physical and psychological consequences (Moorey & Greer 2002, Quarmby et al 2006, Hutton 2008). They are one of the most effective interventions for reducing the impact of chronic pain (Morley et al 1999).

Why people with pain suffer

Chronic pain is defined as pain that has lasted for more than 3 months (The International Association for the Study of Pain 2003). When pain is long term the secondary biological, psychological and social effects of the condition can begin to play a significant role in the increase and maintenance of many difficulties (Turk & Monarch 2002). These difficulties can be extremely wide ranging:

The history of chronic pain models

Developments in psychophysical and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research have helped increase our understanding of the neural correlates of the pain experience and the role of psychological processes in the experience of pain. Imaging studies have shown that despite giving identical external noxious stimuli to a range of participants their reports of pain intensity varied (Coghill et al 2003). fMRI results show that reports of pain intensity do not correlate with stimulus intensity but with the degree of cortical activation in several brain regions that are not only important in pain processing but also cognitive processes. Participants who rated the noxious stimuli as very painful showed greater and more frequent activation of the following areas:

For a more in-depth discussion about psychological factors and pain the reader is directed to Chapter 3 and also Wall (2000) and Melzack (2001). Suggesting that psychological factors influence our experience of and responses to pain is not the same as saying that pain is psychological; rather it is the recognition that physical and psychological factors play a role in the processing and perception of physical symptoms.

In addition to biological and psychological factors influencing pain perception, it is now understood that social factors also play a role (Morris 1993, Frank 1997, Carr et al 2005). We do not live in isolation but within systems such as the family, work, healthcare, friendships and society. A variety of beliefs, messages, rules, stories and narratives exist within these systems, all of which influence our own beliefs and behaviour. The messages and information that we hear about illness and coping play a significant role in the perception of illness and the way in which the illness impacts on our lives.

Using the dualistic model to understand health conditions is now considered to be outdated and unhelpful (Sharpe & Williams 2002). It can result in patients’ pain being unhelpfully labelled as psychogenic or even if they are not told this explicitly patients are very sensitive to the possibility that a clinician believes that someone’s pain is psychological. Many of those suffering from JHS or FM have had this experience. This results in anger, frustration and a feeling of being disbelieved (Gurley-Green 2001) (see Prologue).

Those who have moved away from using the dualistic model now use a biopsychosocial framework (Engel 1977) to help them and the patient understand their condition and the effects that it is having on them and their lives.

The biopyschosocial model highlights the dynamic interaction between biological, psychological and social factors in all health conditions for everyone. The degree to which each of these factors plays a role will differ between individuals but this is seen as normal rather than pathological. This model has been applied to pain (Main & Williams 2002, Waddell 2004) and has placed psychological and social factors firmly in the realm of pain research and practice (Linton 2000).

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Medical interventions can be helpful for some but not all people with chronic pain. Research has suggested that even if these interventions reduce the pain by 30% this does not necessarily result in an improvement in the quality of people’s lives because the secondary psychological and physical effects of pain remain (Dworkin et al 2003). The absence of a cure for everyone with chronic pain has led to the development of psychologically based interventions. The cognitive behavioural model is a psychological model that is used to understand and address people’s distress. It was developed by Beck (1976) and its application to a range of difficulties is now supported by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2007).

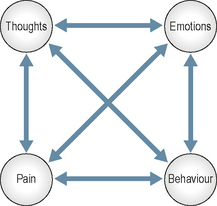

The central tenet of the model is that our thoughts, emotions, behaviour and bodily sensations influence one another (Fig. 8.1).

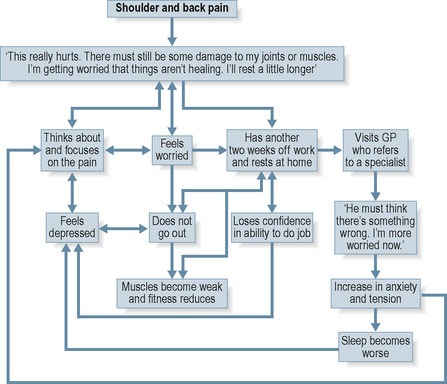

As the diagrammatic form of the cognitive model suggests, the influence between thoughts, feeling, behaviour and the body is not linear but cyclical. One can influence another which can influence another and another and so the cycle continues. If these influences are unhelpful, over time the detrimental impact of the pain can become wide ranging. Figure 8.2 outlines a typical situation that can occur over a few months or years.

Over 40 published randomized controlled trials have assessed the efficacy of cognitive behavioural interventions for chronic pain (Morley 2004). These trials suggest that when compared with waiting list controls, cognitive behavioural interventions are more effective in restoring function, improving mood and reducing disability and unhelpful pain-related behaviours (Morley et al 1999). Compared with a range of heterogeneous interventions (such as those provided by pain clinics, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and educational packages) cognitive behavioural interventions produce significantly greater changes in the pain experience (intensity, unpleasantness and sensation), improved cognitive strategies to manage pain and reduced behavioural expression of pain (Morley et al 1999). McCracken and Turk (2002) support these findings and add that cognitive behavioural interventions lead to an overall decrease in health care costs and an increased chance of returning to work.

The outcome literature suggests that cognitive behavioural interventions help to make a significant impact on improving the physical and psychological function of people with FM (Thieme et al 2006, van Koulil et al 2007, 2008). Clinical outcome measures suggest that people with JHS make significant gains in a pain management programme for people with JHS across a range of physical and psychological measures (Daniel et al 2006). However, to the author’s knowledge there are no studies published on cognitive behavioural interventions for JHS. This may be for the following reasons:

Aims and content of cognitive behavioural interventions

Although cognitive behavioural interventions for chronic pain can be provided by one psychological therapist, those patients whose pain is having a greater physical and psychological impact on their lives may gain more benefit from a multidisciplinary team intervention. The British Pain Society (2007) suggests that the core team should consist of:

Other members that can provide valuable input are:

Cognitive behavioural interventions for chronic pain are typically delivered in a group format known as pain management programmes (PMPs). This approach works well because the team provides consistent and reinforced messages and because group members can gain a great deal from meeting people with the same condition. A debate exists about whether PMPs should be provided for diagnostic groups rather than chronic pain per se (Turk & Okifuji 2001, Daniel 2005, Daniel et al 2006). Whilst the overriding principles and techniques are the same for all chronic pain regardless of the cause, when the pain is related to a specific condition or syndrome that is associated with other difficulties then groups for specific diagnoses may be beneficial because these difficulties could be addressed to some extent within the group context. In addition it has been recognized that those who feel different from the other group members are more likely to leave the group before the end of the intervention (Coughlan et al 1995). The author’s clinical observations suggest that having one or two people with JHS in a group of people with chronic pain not associated with JHS can lead to group disharmony and the people with JHS feeling dissatisfied with the intervention and misunderstood by the team. Conversely, being in a group specifically for people with JHS can provide a containing and supportive environment for the group to develop self-management techniques.

Improving understanding of chronic pain

People who have JHS are more susceptible to injury, dislocation and subluxation (see Chapter 2). Therefore it can be hard, but necessary, for people with JHS to understand the differences between pain that is a result of injury and their long-term chronic pain and to know how to respond to both.

Reducing pain-related distress

Due to the association between thoughts, feelings, behaviour and bodily symptoms it is common for people with chronic pain to experience a range of distressing emotions and those with JHS and FM are no exception (Gurely-Green 2001, Gupta et al 2007, Verbunt 2008). Although research papers allude to JHS being associated with distress, to the author’s knowledge there are no published data on the prevalence of specific psychological difficulties in this population. However, the data collected in a PMP specifically for people with JHS suggest that their distress is similar to those with chronic pain that is not associated with JHS. The types of distress that are commonly reported by people with chronic pain are:

The cognitive behavioural pain literature recognizes that people’s beliefs and thoughts about themselves and their pain can contribute to this distress and reinforce unhelpful behaviours which can increase distress further (Crombez et al 1999, Lamé et al 2005). For example, the belief that having chronic pain takes away everything worthwhile may result in low mood which in turn may result in a reluctance to engage in life outside the home, which has the consequence of lowering activity level which in itself results in many unhelpful effects. Common unhelpful meanings and beliefs about chronic pain that can increase distress and unhelpful behaviours include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree