Introduction

Pregnancy is a common physiological variation of the normal condition of women but is accompanied by various changes, physiological and pathological, which may be associated with severe pain, the inevitable one for most women being that of labour (not addressed here). However, it is important to be aware of the physiological changes in pregnancy, as they will help to explain some of the problems of pain that seem to be specific to pregnancy (Table 14.1). Many of these changes are necessary in response to the development of a rapidly growing intra-abdominal tumour, in particular there will be changes to the musculoskeletal system, augmented by hormonal changes. Alongside this there are changes to other organs and systems within the body, which will have an impact upon the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs used in the treatment of pregnant women.

Table 14.1 Physiological changes in pregnancy

| Gastro Intestinal Tract transit time | ↑ |

| Stomach acidity in 1st and 2nd Trimesters | ↓ |

| Gastric pH | ↑ |

| Circulating blood volume | ↑ |

| Cardiac output | ↑ |

| Renal outflow | ↑ |

| Creatinine clearance | ↑ |

| Body water | ↑ |

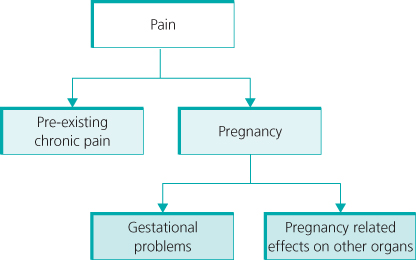

Pregnancy does not offer immunity to the normal vicissitudes of life, and therefore there are many causes of pain in pregnancy which are common to women in normal life (Figure 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Factors leading to pain and discomfort during pregnancy. When there is pre-existing chronic pain, management of these patients may become much more complex, as their change of condition may radically altered the clinical situation.

Musculoskeletal Problems

The development of an intra-abdominal mass will give rise to postural changes secondary to the shift in the centre of gravity of the body, with alterations of the spinal curves, possibly increasing the lumbar lordosis and, thereby, increasing the strain on the zygapophyseal joints. The muscles are also affected, the rectus abdominis muscles being lengthened, along with divarification or diastasis of the muscles. The oblique muscles will be changed not only in length but also the direction of action will be changed. Finally, there is often weakness or poor function of the gluteal muscles, which are important in postural maintenance. The changes in the joints of the lumbar spine and the pelvis are generally secondary to the hormonal changes of pregnancy, in particular the increase in relaxin levels, which has an effect upon the extensibility of connective tissue. This will have a major impact upon the joints of the pelvis, particularly the sacroiliac joints and the pubic symphysis, notably with diastasis of the pubic ramus, but also with the forward rotation of the innominate bones associated with a counternutation (backward movement) of the sacrum, the end result of which is pelvic instability.

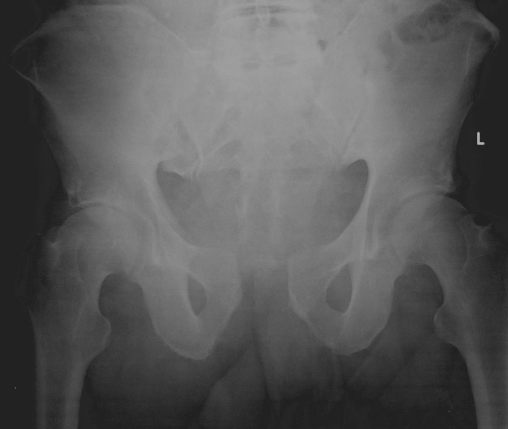

The prevalence of low back and pelvic pain in pregnancy (LBPP) is reported as 72%. This includes simple low back pain, but also isolated sacroiliac joint pain, pain from the symphysis pubis or a combination of all three (Figure 14.2). The predisposing factors are parity, previous LBPP, body mass index and hypermobility.

Figure 14.2 Diastalsis of the pubic symphysis is not uncommon in pregnancy and can lead to considerable pain and disability, with some women developing continuing problems after delivery.

Treatment has been through physiotherapy, with various exercise regimes, but it has been shown that stabilising exercises are beneficial, and there is an increasing volume of evidence to demonstrate that acupuncture is a safe and highly effective method of improving pain and function. There is no evidence for the use of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) machines, outside of labour, in pregnancy, although TENS machines have been used as long as the electrodes are not positioned directly over the abdomen (further information is given in Chapter 18). The use of pelvic belts has been advised, as they can stabilise the sacroiliac joints (Figure 14.3). Finally, there may be problems with the hip joint in pregnancy, namely idiopathic transient osteoporosis of the hip. This is a rare idiopathic disorder presenting with severe hip pain, which is normally self-limiting, resolving spontaneously in 6–24 months post-partum, but the use of agents to prevent the resorption of bone may reduce the duration of symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree