Introduction

As the world increasingly greys, so too does the need for practitioners to gain competence in caring for older adults with a myriad of pain conditions. While many of these patients have suffered from pain for decades, others, because of the accumulation of degenerative pathology in their later years, are relative newcomers to pain. In either case, pain should never be considered normal and because older adults are not simply a chronologically older version of younger patients with pain, unique skills are needed to afford optimal treatment outcomes in these individuals.

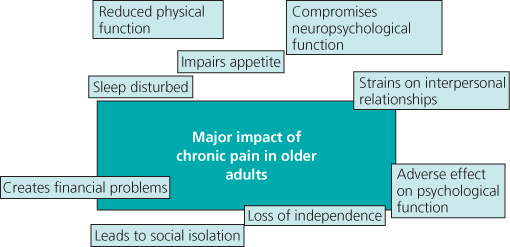

This chapter focuses on chronic or persistent pain because of its greater clinical complexity and treatment challenges. Because aging in the absence of pain also may be associated with deterioration in each of these domains, aggressive treatment of chronic pain in older adults is especially important (Figure 13.1).

Evaluation

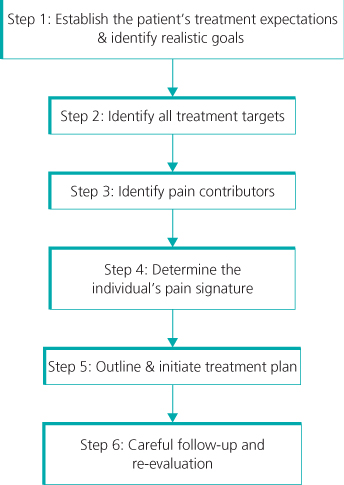

The key to optimising treatment outcomes lies in careful and comprehensive evaluation (Figure 13.2).

Step 1: Establish the Patient’s Treatment Expectations

The first step in evaluation is to establish what the patient expects from treatment and to set realistic goals. If the patient’s treatment expectations are unrealistic (e.g. a pain-free state), these must be reconciled to avoid frustration on the part of both patient and practitioner. Depending upon the setting of care and the patient’s cognitive status, involving the caregiver(s) may be critical at this stage.

Step 2: Identify All Treatment Targets

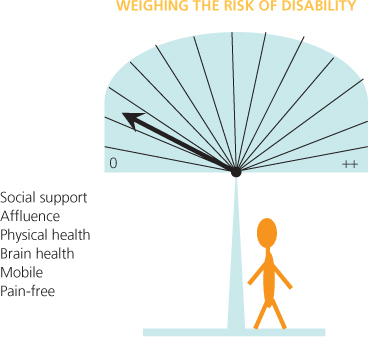

Once realistic treatment expectations and patient goals have been established, the next step is to explore the factors that need to be targeted to improve pain management. Chronic pain may be only one of multiple factors that increase the risk of disability and impair quality of life in older adults. For the older adult with good social support, financial resources, physical and emotional health, and who is independent in mobility and free of pain, the risk of disability is low (Figure 13.3).

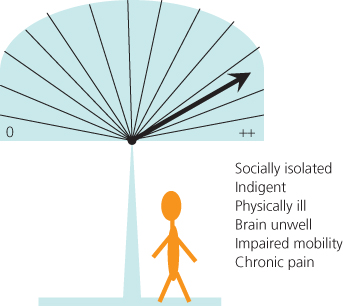

For the individual who is socially isolated, indigent, burdened with multiple medical and psychological comorbidities, immobility and chronic pain, the risk of disability and poor quality of life is quite high (Figure 13.4). It is incumbent upon the practitioner, therefore, to prioritise and tailor chronic pain treatment according to the context in which it exists.

In the older adult with severe dementia, for example, it may be that the dementia itself is the main contributor to impaired function and overall distress. While such a patient’s pain requires treatment, the approach to pain treatment may be very different as compared with the treatment of chronic pain in a cognitively intact, highly functioning individual, as illustrated by the case history example in Box 13.1.