Chapter 10 Pain

Pain assessment

Assessment of children

Physiology and treatment of pain

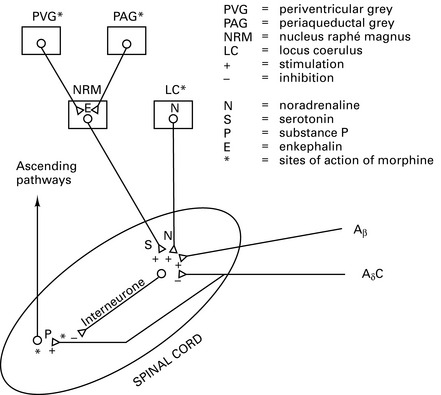

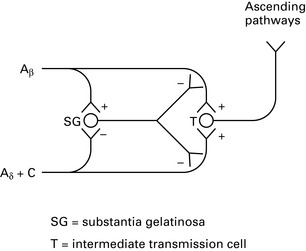

Pathophysiology

Pain in neonates

Techniques in pain treatment

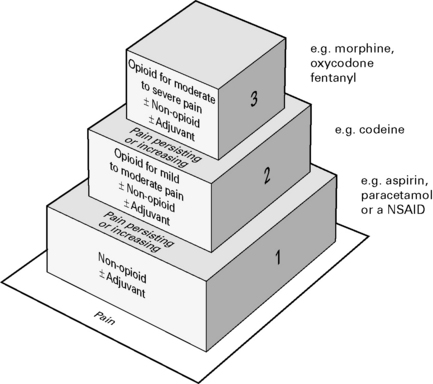

Combination analgesia

Combinations of opioids, NSAIDs and nerve blocks result in improved pain relief and fewer adverse side-effects. Most effective to use a combination strategy using multimodal drugs of increasing potency (Fig. 10.3).

Specific drugs

NSAIDs

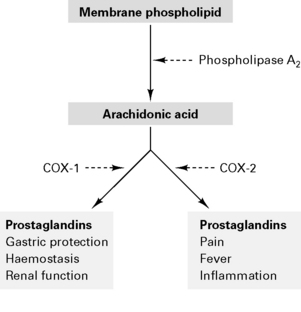

NSAIDs are analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic. Act to inhibit cyclo-oxygenase in the spinal cord and periphery to decrease prostanoid synthesis and diminish post-injury hyperalgesia at these sites. NSAIDs reversibly inhibit cyclo-oxygenase to reduce prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis (Fig. 10.4). Type 1 cyclo-oxygenase (COX-1) is present in gastric mucosa to produce protective prostaglandins and modulates renal function and platelet adhesiveness. Type 2 cyclo-oxygenase (COX-2) is responsible for inflammatory prostaglandins. Drugs which inhibit only COX-2 (rofecoxib, parecoxib) cause fewer gastric, renal and haemorrhagic side-effects. NSAIDs also inhibit neutrophil activation by inflammatory mediators and act centrally on the thermoregulatory centre. There is minimal protein binding with subsequent large volume of distribution.

Side-effects

Guidelines for the Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the Perioperative Period

Royal College of Anaesthetists 1998

Opioids

Opioid receptors are found in high concentrations in the limbic system and spinal cord:

Actions

Nausea and vomiting prevent oral intake. Poor bioavailability because of first pass.

Sublingual. Systemic absorption avoids first pass. Dry mouth reduces absorption.

Transdermal. Rate of absorption ∝ lipid solubility. Reduced absorption with vasoconstriction.

Intra-articular. Action via intra-articular opioid receptors.

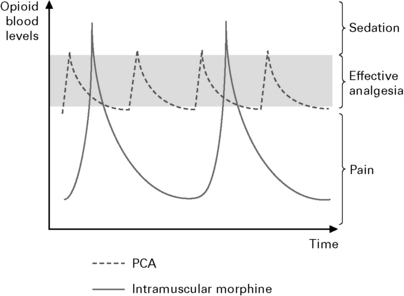

Patient controlled analgesia (Fig. 10.5).

MHRA Guidance 2007

α2-Agonists (e.g. clonidine)

α2-agonists have the following characteristics: