Pain

Cristin A. McMurray

Pain is a complex process influenced by physiologic and psychologic factors. It is estimated that in 2005, approximately 80% of all surgeries were performed on an outpatient basis. Surveys indicate that 80% of patients experience moderate to severe pain postoperatively (1). This is an astounding number considering the advancements in technology regarding drug delivery systems and the improved number and type of medications for pain relief that are available.

WHY DO WE CARE ABOUT PAIN?

In addition to the basic humanitarian desire to alleviate pain in patients, there are actually a number of important consequences to postoperative pain in the ambulatory setting (see Box 15.1). The experience of pain has numerous effects on various organ systems throughout the body that can develop into problematic sequellae for patients. Most notably in the postoperative setting, pain may lead to splinting and reduced cough. These conditions, in turn, lead to atelectasis and hypoxemia. Pain also increases myocardial oxygen demand, which, in combination with the aforementioned hypoxemia, could expose the heart to ischemia. Pain affects the gastrointestinal (GI) system by reducing motility and gastric emptying, which can increase nausea and vomiting. Additionally, pain can cause urinary retention, hyperglycemia, and anxiety. The reduced mobility from pain may expose the patient to the risk of pressure sores and possible deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (2). All of these problems may lead to longer postanesthesia care unit (PACU) stays and possible unanticipated hospital admissions; it makes medical as well as financial sense to optimize pain control in the outpatient setting. Recent Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) guidelines stress the importance of pain assessment (also known as the fifth vital sign), good multidisciplinary pain management, patient education, and monitoring the performance of the health care team in carrying out these guidelines.

Box 15.1

Physiologic Effect of Pain

Splinting and reduced cough

Atelectasis and hypoxemia

Increase in myocardial oxygen demand

Reduced gastric motility and emptying

Increased nausea and vomiting

Urinary retention

Hyperglycemia

Anxiety

Historically, physicians are noted to have undertreated pain; fear of causing respiratory depression leads many clinicians to undertreat pain. The goal should be a balance, or perhaps a better understanding of the way that pain affects patients and ways that patients affect their own pain perceptions. With the array of drugs in the therapeutic arsenal, a little empathy and openness to some “alternative” modalities of pain modulation, anesthesiologists can make a difference to patients and the impact pain has in the postoperative period.

A BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL OF PAIN

Understanding the ways in which pain affects patients is extremely important, even for what are considered, “minor” surgeries in an office setting. As clinicians have less time to spend with these patients than in a hospital setting, it is crucial to be able to anticipate patients’ responses to pain they may undergo. The biopsychosocial model of pain serves to elucidate some of the factors that may not come immediately to mind if one regards pain as a purely physical state. This sensory component is certainly important, but there are other aspects to consider (see Box 15.2). There are emotional, cognitive, behavioral, environmental, and social factors involved with an individual’s response to pain. In the acute setting, the psychosocial components are probably more relevant, but many patients coming for surgery may have issues with chronic pain (see Box 15.3).

Box 15.2 • The Biopsychosocial Model of Pain

Sensory component

Emotional component

Cognitive aspects

Behavioral factors

Environmental and social factors

Box 15.3 • Patient Issues Affecting Anesthesia

Loss of control

Feelings of helplessness

May exacerbate pain

Another issue for many patients undergoing anesthesia for surgery is a loss of control; feelings of helplessness may also accompany their postoperative pain experience and exacerbate their pain. Physicians should try to remain aware of patients’ individual experiences and try to tailor their interpersonal and medical treatment accordingly (3).

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT OF PAIN

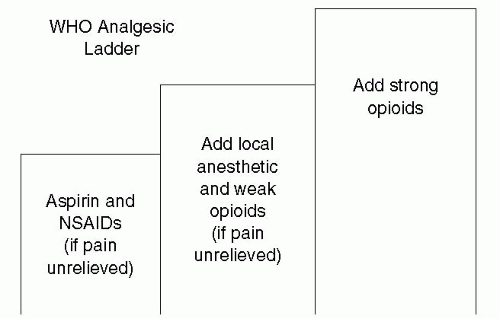

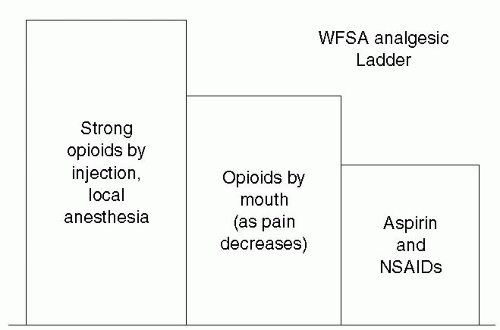

There are various models illustrating basic principles in treating acute pain. The World Health Organization (WHO) and World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists (WFSA) have both created “Analgesic Ladders” to help providers think about how to approach pain.

The WHO Analgesic Ladder (see Figure 15.1) was introduced to improve pain control in patients with cancer pain. It also educates the practitioner regarding the management of acute pain as it employs a logical strategy to pain management. As originally described, the ladder has three rungs.

The WFSA Analgesic Ladder (see Figure 15.2) has been developed to treat acute pain. Initially, the pain can be expected to be severe and may need controlling with strong analgesics in combination with local anesthetic blocks and peripherally acting drugs (4).

LOCAL ANESTHETICS

A small amount of local anesthesia can go a long way in preventing severe postoperative pain. It can be administered for the actual surgery itself, and, if properly maintained in the postoperative period, may serve as the major component of pain management for a patient. This may be extremely beneficial in patients whose respiratory and cardiac status may not be ideal.

Local anesthetics work to prevent depolarization in nerve cell membranes by inhibiting sodium channels. There are a number of local anesthetic drugs

available which differ in their duration of action and toxicity profiles (see Table 15.1).

available which differ in their duration of action and toxicity profiles (see Table 15.1).

Figure 15.1. The World Health Organization (WHO) Analgesic Ladder. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. |

In the ambulatory setting, local can be used in a variety of ways by both surgeons and anesthesiologists.

The most basic use for local is infiltration of the wound, usually done by surgeons, either before, during, or after the surgery. Sometimes this might be all that the patient requires. In other instances, the addition of intravenous (IV) sedation may serve to help the patient tolerate the local infiltration and the procedure itself. Other times, the surgeons may inject local anesthetic at the end of a general anesthetic to help with postoperative pain. Ideally the local anesthetic would serve to maintain the patient during the immediate postoperative course until other pain control methods could begin to work. Interestingly, there are current studies on continuous wound infusion pumps that administer local anesthetics; results have been mixed, but there is

evidence that they may be as effective as patient-controlled anesthesia (PCA) for some types of postoperative pain (1).

evidence that they may be as effective as patient-controlled anesthesia (PCA) for some types of postoperative pain (1).

Figure 15.2. The World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists (WFSA) Analgesic Ladder. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. |

Table 15.1. Local anesthetic doses and properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree