Background

Opioids are the oldest (Figure 20.1) and the most important analgesics in the management of acute and cancer pain but their use is more controversial and challenging in chronic non-malignant pain. Opioids can be effective and safe also in chronic non-malignant pain if they are used wisely, with a thorough understanding of the patient and the pharmacology of opioids.

Figure 20.1 Opium that is derived from the poppy, Papaver somniferum, has been used in pain relief for millenia.

Recent advances in pharmacogenetics have increased our understanding of why opioid responses vary so much between individuals and conditions. Opioids often cause adverse effects that can be serious. This chapter discusses the use of opioids in chronic pain. It provides information about the efficacy of opioids in different chronic pain conditions, guidelines that have been introduced to help the clinician in patient selection and follow-up, and the pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenetic differences of opioids.

The Endogenous Opioid System

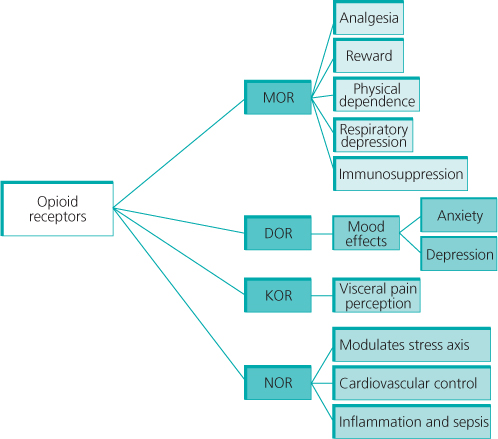

Opioid receptors and their endogenous ligands modulate numerous physiological functions, such as nociception, mood, reward, learning, stress response, hormonal functions, appetite, sleep, immune function and gastrointestinal function. Three receptor classes – mu (MOR), delta (DOR) and kappa (KOR) – have been described by pharmacological approaches. More recently, using cloning techniques, an additional type of opioid receptor has been found – the ORL1 (orphanin receptor like) or NOP (nociceptin) receptor. MOR is the major molecular target for morphine. Opioid receptors have a wide range of functions, some of which are outlined in Figure 20.2.

Figure 20.2 Some potential roles of opioid receptor subtypes. MOR = mu opioid receptor; DOR = delta opioid receptor; KOR = kappa opioid receptor; NOR = nocieptin/orphanin FQ peptide opioid receptor.

Opioid receptors are located throughout the central and peripheral nervous system. Opioid receptors in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord have an important role in the modulation of pain. Opioid receptors in the brain stem are involved in the regulation of arousal, respiration and both anti- and pro-nociceptive effects. Opioid receptors are found almost everywhere in the cerebrum and cerebellum. In the periphery, opioids are involved in the regulation of gastrointestinal function. Activation of MORs in the gut leads to increased absorption of water from the stools and spasticity of the gut. Peripheral opioid receptors are involved in the regulation of inflammation and the immune system.

Opioids for Chronic Non-cancer Pain: What is the Evidence for Efficacy?

Several systematic reviews have indicated moderate short-term efficacy (up to 3 months) of opioids in both osteoarthritis-related and neuropathic pain. Both weak and strong opioids were better than placebo for pain. Mean pain relief with strong opioids in these studies was about 30% in both neuropathic and osteoarthritic pain when mean daily doses of 40 mg of oxycodone or 80–100 mg of morphine were used. The effect size for improved function has, however, been small. Variation in response between patients has been considerable and the placebo response has been quite significant. Musculoskeletal pains other than osteoarthritis have not shown long-term benefit from opioids. Opioids may be efficacious for short-term pain relief for back pain whereas their long-term efficacy is unclear.

Aberrant medication-taking behaviour has been reported to occur in up to one in four back pain patients. Continuous opioid therapy is rarely advisable for refractory chronic daily headache because of limited efficacy. There are no controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of opioids in visceral pain or fibromyalgia.

Opioids should be used only if there has been a comprehensive assessment that indicates potential efficacy. Guidance for the initiation of treatment with strong opioids and requirements for successful therapy with opioids are given in Boxes 20.1 and 20.2, respectively.

Opioid Therapy can be Introduced By the GP if:

- the cause of the pain is known

- the pain is likely to respond to opioids

- opioids are needed for a restricted period only

- the patient does not have any major psychosocial problems

- the patient does not have a history of drug or alcohol abuse

The Patient Should Be Evaluated for Opioid Therapy At a Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic if:

- the cause of the pain problem is not clear

- the patient is young

- opioid therapy is expected to last for a prolonged period (several months)

- the patient has major psychosocial problems

- the patient has a history of drug or alcohol abuse

Opioid Therapy is Likely to be Successful if the Prescribing Physician:

- has adequate knowledge of opioid pharmacology

- considers carefully the benefits and harms of opioid therapy

- takes responsibility for the follow-up of opioid therapy and takes careful records

- is willing to consult a pain specialist when needed

- does not increase the opioid dose without careful consideration

- titrates down opioid therapy if the patient does not receive significant benefit from it

Opioid Therapy is Likely to be Successful if the Patient:

- has been informed of the potential benefits and harms of opioid therapy

- is willing to follow instructions regarding opioid therapy

- is willing to actively pursue other methods of pain relief (physical activity, pain management groups)

- is willing to provide a urine test for opioid screening if considered necessary

Risks and Benefits of Opioid Therapy

The biggest difficulty in the long-term management of chronic pain with opioids is risk-benefit analysis (Figure 20.3). Some risks are common and are usually easy to prevent (e.g. constipation) whereas others (e.g. opioid addiction) are rare, difficult to predict and to treat. Several risk assessment tools have been developed for opioid misuse by chronic pain patients. Some pain clinics use an opioid contract (Box 20.3) and urine screening.

Figure 20.3 Titrating the dose – balancing between analgesia and adverse effects – is the challenge for managing pain with opioids.

There is some evidence to suggest that combining CBT with long-term opioid therapy may improve analgesia and reduce dose escalation. Both long duration of therapy and high opioid doses are related to more adverse effects.

A Contract in Opioid Therapy Should Include at Least the Following Aspects:

- Description of opioid therapy including possible benefits and harms

- The patient is obliged to inform the physician or the team if he/she uses other analgesics or psychotropic drugs

- The patient should not ask another physician to prescribe analgesics

- The prescribed opioid should be taken as advised by the physician and opioids should never be given to another person

- Opioids should be kept in a locked place and special care should be taken to avoid children having access to them. The police should be informed if opioids are stolen

- Opioids can decrease psychomotor function even though tolerance to a stable dose usually develops within 2–3 weeks. Dose increases, additional doses, other psychotropic drugs, sedatives and opioids decrease the psychomotor function further. These facts need to be considered if the patient needs to be capable of operating machines or driving a car

- The patient needs a document (either from the physician or the pharmacy) indicating the medical need for the opioid prescription when travelling abroad. The amount of opioids allowed for personal use is limited

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree