CHAPTER 12 Opioid Analgesics

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

The term opioid analgesics refers to medications that act on opioid receptors and are used for pain relief. Although the term narcotic has also been used to describe these medications in the past, opioid analgesic is the preferred term now that the word narcotic has taken on negative connotations.1 The term weak (or weaker) opioid analgesics is sometimes used to refer to compound medications combining simple analgesics such as acetaminophen with low doses of codeine or tramadol. Moderate or strong (or stronger) opioid analgesics, by definition, exclude weak opioid analgesics. The terms mild and major are also occasionally used to differentiate weaker opioids from stronger opioids. Other methods of classifying opioids have been proposed based on their origins (i.e. endogenous, opium alkaloids, semi-synthetic, fully synthetic) or effects on receptors (i.e. full/partial/mixed agonists). Regardless of how they are classified, opioids may also be compared in terms of relative strength by using tables that estimate equivalence doses for different opioids.

Opioid analgesics can be divided into three categories: sustained-release opioids (SROs), immediate-release opioids (IROs), and long-acting opioids (LAOs).2,3 SROs are also known as continuous release (CR) or extended release (ER), and release medication continuously from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract after ingestion or transdermally via a reservoir; they are therefore used for continuous pain control. SROs include medications such as morphine-ER, oxycodone-CR, oxymorphone-ER, and transdermal fentanyl (TDF). IROs have a rapid onset of analgesia, are short acting, are used for breakthrough pain or acute pain, and include medications such as oxycodone-IR, hydrocodone, and morphine sulfate-IR. LAOs are taken according to a regular dosing schedule to minimize fluctuation in effective concentrations and include medications such as methadone and levorphanol.

Although the terms addiction and dependence are often used interchangeably, their meanings are very different. Addiction refers to a neurobiologic disease with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors characterized by behaviors that include the compulsive use of a psychoactive substance despite the harms endured; it involves loss of control. Dependence is a state of physiologic adaptation induced by the chronic use of any psychoactive substance, and can occur independently of any addiction.4 Addiction is always a clinical problem, whereas dependence is not.5,6 The term pseudoaddiction is sometimes used to describe a scenario in which patients seek additional medications because their current pain relief is not adequate.7

History and Frequency of Use

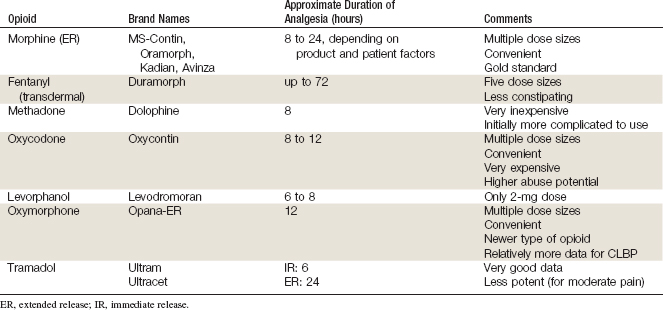

In patients with severe pain related to cancer, opioid analgesics have been considered the standard of care for pain management for many years, despite the lack of high-quality evidence supporting either efficacy or safety with long-term use. For severe pain not related to cancer, there has long been a bias by many physicians in North America against prescribing opioid analgesics. This perception is likely due to misinformation among physicians about adverse events related to opioid analgesics, regulation and monitoring of certain opioid analgesics, and a lack of understanding about the impact of severe pain on quality of life.8 This position has slowly been changing in recent decades, perhaps due to legislation in certain states in the US mandating continuing medical education about chronic pain (e.g., California). Studies began to appear approximately 10 years ago that suggested opioid analgesics could be both safe and effective in well-selected patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP).9,10 Today, many spine centers offer opioid analgesics to patients with moderate or severe CLBP refractory to other medications or interventions (Table 12-1).9,11,12

A study was conducted to examine health care utilization in patients with mechanical low back pain (LBP) as defined by one of 66 related ICD-9 codes.13 Data were obtained from utilization records of Kaiser Permanente Colorado, a health maintenance organization with 410,000 enrollees in the Denver area. Pharmacy records indicated that 29% of patients had a claim for opioids. A study was conducted to estimate the direct medical costs focusing on analgesic medication used for mechanical LBP as defined by one of 66 ICD-9 codes.13 Data were obtained from utilization records of 255,958 commercial members enrolled in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System in 2001. Among the 9417 patients (56%) with a pharmacy claim for analgesics related to their LBP, the most frequent analgesic was opioids (33%), followed by opioids and NSAIDs (26%), and opioid and other analgesics (9%). Most opioid use was short-term, with a duration of 1 to 30 days (71%), although a substantial portion had a duration of 31 to 90 days (14%). Smaller proportions of patients used opioids for 90 to 179 days (6%), and more than 180 days (9%). In specialty spine practices, opioids were part of the plan after a single visit for 3% of more than 25,000 patients, 75% of whom had pain for longer than 3 months.12

In a university orthopedic spine clinic, opioids were prescribed for 66% of patients and 25% received long-term opioid (LTO) treatment.11 It has been reported that the proportion of patients receiving opioid analgesics is higher in secondary care settings than in primary care settings and that those with poor physical function and greater distress were more likely to receive them.14 In a retrospective study of 165,569 employees covered by three large employer-sponsored health plans in the United States, almost half (45%) of the 13,760 patients who had reported LBP had claims for opioid analgesics in the previous year.15 Factors associated with an increased use of opioid analgesics included comorbidities such as hypertension, arthritis, depression, anxiety, cancer, and prior surgery.

Procedure

There are two ways to dose opioid analgesics: pain-contingent or time-contingent. Pain-contingent dosing is defined as medication taken when pain occurs (as needed), whereas time-contingent dosing is defined as medication taken on a regular schedule based on the duration of analgesia rather than intensity of symptoms at that time (by the clock). Based on the authors’ clinical experience managing patients with CLBP, it appears that time-contingent dosing of opioids generally provides better long-term pain control, fewer side effects, and improved compliance when compared to pain-contingent use. SROs or LAOs are typically taken on a time-contingent basis, whereas IROs are taken on a pain-contingent basis. The duration of action of SROs and LAOs is somewhat variable, and depends on rates of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). Many patients require dosing intervals that are shorter than generic manufacturer recommendations.16,17 An IRO may be prescribed for breakthrough pain in those taking SROs or LAOs.

An occasional patient may experience better pain control with an IRO administered on a time-contingent basis than with SROs or LAOs. It is not uncommon for the physician to have to try several different opioid analgesics to identify which one is best for a particular patient. An individual patient’s response is at least in part based on a genetic predisposition18; some CLBP patients may not respond to opioid analgesics at all, despite trying different medications. There is no universally correct dose of opioid analgesics for CLBP; treatment should be initiated at conservative doses until patient response can be assessed. Both the dose and the dosing schedule must be titrated for each patient according to analgesic efficacy and side effects. Most opioids do not have a true ceiling effect and therefore have no maximum dose. However, side effects increase with dose and can interfere with improvements associated with analgesia.

General guidelines for the use of opioid analgesics are summarized in Table 12-2. Specific guidelines for individual medications are summarized here.

TABLE 12-2 General Recommendations for the Use of Opioid Analgesics in the Treatment of Chronic Pain

| Recommendation | Components |

|---|---|

| A careful evaluation of the patient | History Physical examination Review of imaging Review of medical records |

| A treatment plan that states the goals of therapy | — |

| Informed consent (verbal or written) | Potential benefits Potential risks Probable and possible side effects Consequences of abuse, diversion, or illicit use of opioids |

| Therapeutic trial | If good response with acceptable side effects, continued treatment |

| Regular follow-up visits for assessment and documentation | Efficacy Side effects Signs of abuse or diversion |

| Consultation when necessary with specialists | Psychology/psychiatry Chemical dependence |

| The maintenance of good medical records | — |

Morphine

Morphine, available in both IR and ER formulations, remains the gold standard against which other analgesics are compared. Morphine has been shown to be safe and efficacious for many patients with CLBP at an average final dose of 105 mg/day (range 6 to 780 mg).19,20 Sustained-release versions of morphine can provide analgesia for 8 to 24 hours, depending on the formulation and individual patient factors (e.g., ADME). There are many doses of morphine available, which facilitates titration. The dose of morphine can be titrated upward once or twice weekly until a satisfactory level of pain control and side effects is achieved. For breakthrough pain, immediate-release morphine is available in doses of 15 or 30 mg; one every 4 to 6 hours is preferred.

Transdermal Fentanyl

TDF has been shown to be effective in the treatment of CLBP in opioid-naive patients at a mean dose of 57 mg/hr (range 12.5 to 250 mg), though caution is strongly advised when prescribing TDF to opioid-naive patients, and harms should be closely monitored.16,20,21 TDF can be more convenient than oral formulations because in most patients the patch needs to be changed only every 2 to 3 days. There may also be less constipation with the transdermal route of administration than with oral administration.

Oxycodone

Oxycodone is an effective analgesic for CLBP at an average dose of 60 mg per day, with a wide range.16,19,22–25 Drawbacks to this otherwise good medication include a relatively high cost, and increased prevalence of abuse and diversion when compared with other opioid analgesics.

Oxymorphone

Oxymorphone is the newest opioid analgesic and perhaps the best studied specifically for CLBP. It is most often administered twice daily, at an average dose of 39 to 79 mg/day.22,26 Immediate-release oxymorphone is also available for breakthrough pain.

Methadone

Methadone has gained in popularity as an opioid analgesic because it is highly effective, has high biological availability, has no known active metabolites, has no known neurotoxicity, is relatively inexpensive, and may produce less opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) than other opioid analgesics.27–29 However, methadone can interact with several medications, can cause prolonged QT, should not be used in hepatic failure, and it may be more difficult to initiate this therapy. It is important to note that because of the pharmacokinetics of methadone, its dose should not be increased more frequently than once every 5 to 7 days. Once a steady state is reached, analgesia usually lasts for 8 hours.

Levorphanol

Levorphanol has been shown to be effective in both nociceptive and neuropathic pain.30 Many patients need 8 to 12 mg every 6 to 8 hours. The 2 mg pill size is therefore inconvenient and has resulted in manufacturer shortages in recent years.

Tramadol

Tramadol is a semisynthetic opioid (analogue of codeine) available alone or combined with acetaminophen (e.g., Ultracet), and is also available in an extended-release formulation. It has been shown to be effective in patients with CLBP at an average dose of 158 mg/day; the maximum safe daily dose is 400 mg.19,31–33

Regulatory Status

The opioid analgesics discussed in this chapter are all approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for primary indications related to pain, although not specifically CLBP. These medications are only available by prescription, and many are subject to additional monitoring required for controlled substances (Figure 12-1).

Theory

Mechanism of Action

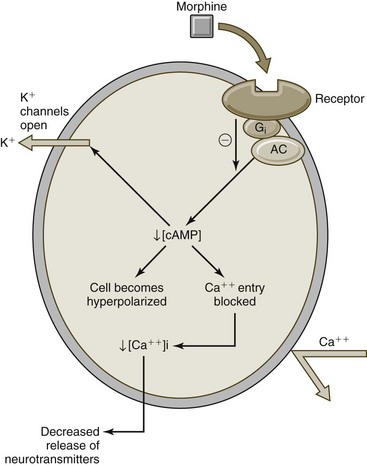

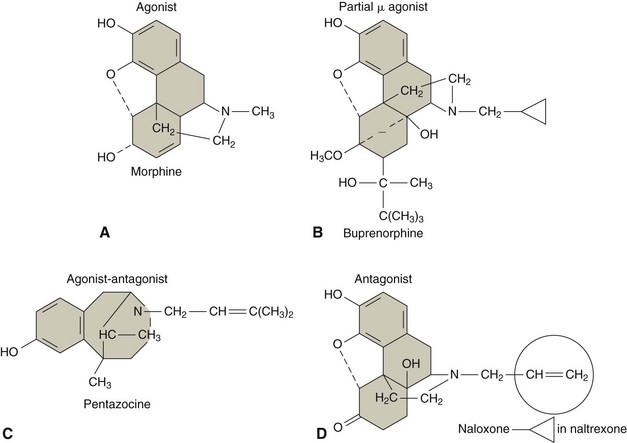

The analgesic effects of opioids are thought to be related to their ability to bind opioid receptors, which are located primarily in the central nervous system (CNS) and GI system (Figure 12-2). Different medications are thought to exhibit different affinities for specific opioid receptors, including the main µ (mu), κ (kappa), and δ (delta) opioid receptors.5 Binding to opioid receptors is thought to inhibit transmission of nociceptive input from the peripheral nervous system (PNS), activate descending pathways that modulate and inhibit transmission of nociceptive input along the spinal cord, and also alter brain activity to moderate responses to nociceptive input.35 As new opioid receptors are discovered and the properties of known opioid receptors are better understood, additional medications may be developed to selectively act on specific receptors to improve efficacy or decrease side effects (Figure 12-3).

Figure 12-2 Mechanism of action for opioid analgesics (e.g., morphine).

(Modified from Wecker L: Brody’s human pharmacology, ed. 5. St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Figure 12-3 Molecular structure of medications with different effects on opioid receptors.

(Modified from Wecker L: Brody’s human pharmacology, ed. 5. St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Although tramadol is not chemically related to stronger opioid analgesics, it acts by weakly binding both µ- and δ-opioid receptors in the CNS. Tramadol may also interfere with serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in descending inhibitory pathways.13 Tramadol is only partially affected by the opiate antagonist naloxone.36

Indication

Short courses of opioid analgesics may be indicated for patients with moderate to severe CLBP who are unable to resume their activities of daily living and have failed to respond to other interventions. The severity of pain reported by patients is subjective, but can nevertheless be measured using simple instruments such as the visual analog scale (VAS) or numerical pain rating scale (NPRS), or more complex instruments such as the McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ) or Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). Repeated administration of these measures in patients with CLBP may be helpful in deciding whether or when opioid analgesics may be warranted if the severity of pain worsens or crosses a particular threshold established by the patient and clinician (Table 12-3).

TABLE 12-3 Indications for Opioid Analgesics

| Generic Name | Trade Name | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine (ER) | MS-Contin, Oramorph | Moderate to severe pain that requires repeat dosing with potent opioid analgesics for more than a few days |

| Kadian, Avinza | Moderate to severe pain that requires a continuous, around-the-clock opioid for an extended period of time | |

| Fentanyl (transdermal) | Duramorph | Pain that is not responsive to non-narcotic analgesics |

| Methadone | Dolophine | Pain that is not responsive to non-narcotic analgesics, detoxification treatment of opioid addiction, maintenance treatment of opioid addiction |

| Oxycodone | OxyContin | Moderate to severe pain that requires a continuous, around-the-clock analgesic for an extended period of time |

| Levorphanol | Levodromoran | Moderate to severe pain where an opioid analgesic is appropriate |

| Oxymorphone | Opana ER | Moderate to severe pain that requires a continuous, around-the-clock opioid for an extended period of time |

| Tramadol | Ultram, Ultram ER | Moderate to moderately severe chronic pain in adults who require around-the-clock treatment of their pain for an extended period of time |

| Ultracet | Short-term management of acute pain |

ER, extended release.

Source: www.drugs.com.

Additional instruments may also be helpful in identifying those patients with CLBP in whom opioid analgesics may be indicated. From a behavioral and psychological health perspective, it has been suggested that patients with chronic pain (including CLBP), can be divided into three categories: (1) adaptive coper, (2) dysfunctional, and (3) interpersonally distressed.37 A questionnaire has been developed for use by pain management specialists to help make this determination. Of the three categories, only adaptive copers are likely to respond to longer courses of opioid analgesics. Adaptive copers typically demonstrate coherent symptoms, including pain that is consistent with the suspected underlying pathology, function that is concordant with their impairment, and mood that is appropriate to their levels of pain and function. Furthermore, adaptive copers have no history of addictive disease, and reasonable goals and expectations about the proposed intervention.

Assessment

Before receiving opioid analgesics, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Prescribing physicians should also inquire about medication history to note prior hypersensitivity or allergy, or adverse events with similar drugs, and evaluate contraindications for these types of drugs. Clinicians may also wish to order a psychological evaluation if they are concerned about the potential for medication misuse or potential for addiction in certain patients. Diagnostic imaging or other forms of advanced testing is generally not required prior to administering opioid analgesics for CLBP.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Weak Opioid Analgesics

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found moderate-quality evidence to support the efficacy of codeine and tramadol for the management of CLBP.38 That CPG also found evidence that the efficacy of different weak opioid analgesics was comparable.

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found insufficient evidence to support either weak opioid analgesics for people who do not obtain adequate pain relief with acetaminophen.39 That CPG also found limited evidence to support the efficacy of tramadol for CLBP. That CPG concluded that short-term use of weak opioid analgesics could be considered for CLBP, and that the decision to continue should be based on the measured response.

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found strong evidence to support the efficacy of weak opioid analgesics with respect to short-term improvements in pain and function for CLBP.40 That CPG recommended short-term use of weak opioid analgesics for CLBP.

The CPG from Italy in 2007 found evidence to support the efficacy of tramadol with respect to improvement in pain for CLBP.41 That CPG also recommended that a combination of acetaminophen and weak opioid analgesics be considered when NSAIDs or acetaminophen do not result in adequate pain relief.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate evidence to support the efficacy of weak opioid analgesics with respect to improvements in pain.42 That CPG concluded that weak opioid analgesics could be an option for managing CLBP in patients with severe or disabling pain who do not achieve adequate relief with acetaminophen and NSAIDs.

Strong Opioid Analgesics

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found very low-quality evidence to support the efficacy of strong opioid analgesics for the management of CLBP.38

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found some evidence to support the short-term use of strong opioid analgesics for people with severe or disabling pain who do not obtain adequate pain relief with acetaminophen or weak opioid analgesics.39 That CPG also recommended that the decision to continue using strong opioid analgesics should be based on a demonstrated response to treatment. That CPG also reported that patients requiring longer-term use of strong opioid analgesics be referred to pain management specialists who can oversee the use of the medication.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate evidence to support the efficacy of strong opioid analgesics with respect to improvements in pain.42 That CPG concluded that strong opioid analgesics could be an option for managing CLBP in patients with severe or disabling pain who do not achieve adequate relief with acetaminophen, NSAIDs, or weak opioid analgesics.

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 12-4.

TABLE 12-4 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Opioid Analgesics for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Opioids | ||

| 38 | Belgium | Moderate evidence to support use |

| 39 | United Kingdom | Short-term use could be considered based on measured response |

| 40 | Europe | Recommended for short-term use |

| 41 | Italy | Recommended when NSAIDs or acetaminophen do not adequately reduce pain |

| 42 | United States | Recommended when NSAIDs or acetaminophen do not adequately reduce pain |

| Strong Opioids | ||

| 38 | Belgium | Low-quality evidence to support use |

| 39 | United Kingdom | Some evidence to support use when acetaminophen or weak opioids do not adequately reduce pain |

| 42 | United States | Could be an option when acetaminophen, NSAIDs, or weak opioids do not adequately reduce pain |

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Systematic Reviews

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 2006 by the Cochrane Collaboration on opioids for CLBP.44 A total of four RCTs were included, three comparing tramadol to placebo, and one comparing opioids to naproxen.24,31–33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree