31

Ophthalmic emergencies

Introduction

A significant proportion, generally around 6 % of the workload of the Emergency Department (ED), is made up of patients with ophthalmic problems (Ezra et al. 2005). Tan et al. (1997) found a lack of basic ophthalmic training for ED Senior House Officers leading to a lack of confidence on their part in the management of eye emergencies. This lack of confidence on the part of junior doctors is reflected in the nursing teams of many EDs, although Ezra et al. (2005) found that nurses were significantly more accurate than junior doctors in their assessment of ED patients, and combined with the apparent health of many ophthalmic patients, can lead to inappropriate management in the ED.

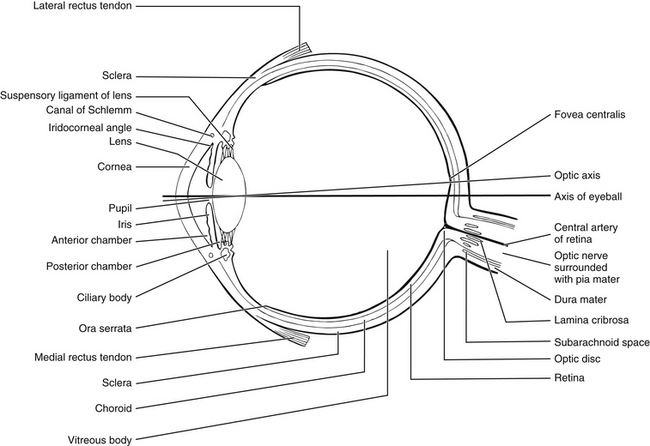

Anatomy and physiology of the eye (Fig. 31.1)

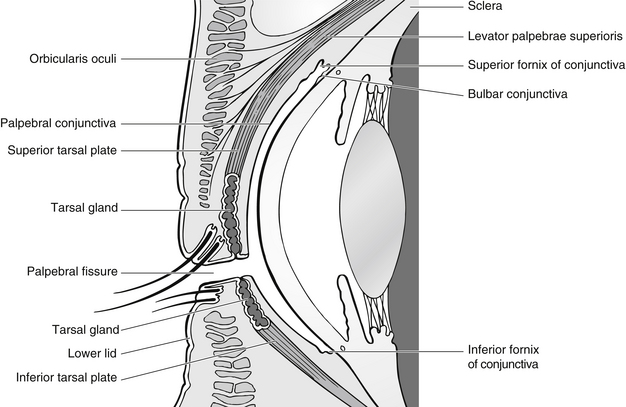

Eyelids

The lids are layered structures covered on their outer surfaces by skin and on their inner surfaces by conjunctiva (Fig. 31.2). In between is subcutaneous tissue, the orbital septum of which thickens within the lids to form fibrous tarsal plates that give structure to the lid. The upper lid contains the levator muscle and the lower contains the inferior tarsal muscle, which retracts it. The lids are maintained in position by the medial and lateral canthal tendons that attach to the periosteum. The lids are closed by the orbicularis muscle.

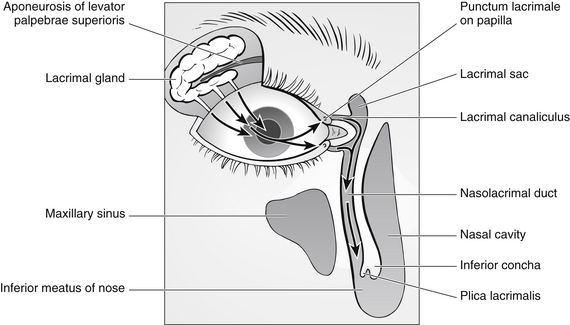

Lacrimal system

The tear film is composed mainly of watery fluid from the lacrimal gland (99 %), which is situated in the lacrimal fossa of the frontal bone in the orbit. The other important components of the tear film are mucin from the conjunctival goblet cells and oil from the Meibomian (tarsal) glands and the glands of Möll and Zeiss. The tear film is distributed over the surface of the eye by gravity, capillary action of the puncta and canaliculi and the eyelids. The tears leave the eye by evaporation and by way of the puncta, the upper of which takes around 30 % of the unevaporated tears and the lower around 70 %. From the puncta, the tears flow into the canaliculi, into the common canaliculus and then into the lacrimal sac and through the nasolacrimal duct (Fig. 31.3).

Cornea

The transparent cornea forms the anterior one-sixth of the globe. Its curvature is higher than that of the rest of the globe and it is the main structure responsible for the refraction of light entering the eye. It is an avascular structure which is nourished by the aqueous humour, the capillaries at its edge and from the tear film. Microscopically, it consists of five layers:

• the epithelium – consists of five layers of cells centrally, ten or more at the limbus. Running between the cells are the nerve endings of sensory nerve fibres, which are sensitive mainly to pain. The epithelium regenerates by the movement of cells from the periphery towards the middle

• Bowman’s layer – is acellular and consists of collagen fibres

• substantia propria or stroma – comprises 90 % of the thickness of the cornea. It is transparent and fibrous, and is made up of lamellae of collagen fibres arranged parallel to the surface. This arrangement ensures corneal clarity

• Descemet’s membrane – a strong membrane which is the basement membrane of the endothelium

• endothelium – a single layer of flattened cells which plays a major role in controlling the hydration of the cornea by a barrier and active transport method. Loss of endothelial cells leads to corneal oedema and lack of clarity.

The uveal tract

The ciliary body is continuous with the choroid and the margin of the iris. It contains the ciliary muscle used to change the shape of the lens during accommodation. Its outer, pigmented layer is continuous with the retinal pigment epithelium. Its inner, non-pigmented layer produces aqueous humour. The lens attaches to the ciliary body by a suspensory ligament whose fibres are known as zonules.

Assessing ophthalmic conditions

• how long the patient has had symptoms for and whether they are getting worse

• rapidity and mode of onset (Box 31.1)

• is vision reduced and to what degree?

• degree, type and location of pain

• is there any discharge, watering or photophobia?

• has the patient had this, or a similar problem before?

• are there any concurrent systemic problems?

Discussion of systemic problems and medication is important as it can point to possible ophthalmic problems. For example, there is a link between ankylosing spondylitis and uveitis, and a link between rheumatoid arthritis and dry eyes, and there are many ophthalmic side-effects of systemic drugs. The assessing nurse needs to investigate any pre-existing ophthalmic or other medical conditions. Of particular importance are conditions such as glaucoma, iritis (uveitis) and blepharitis; systemic conditions such as diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis; and any drug therapy, as all of these may affect the health of the eye.

Visual acuity

The number for this line is indicated on the Snellen chart, just above or just below the letters. If part of a line only is read, this may be recorded as the line above plus the extra letters, or the line below minus the missed letters. For example, if the patient reads the ‘12’ line except for one letter, at 6 m, it should be recorded as 6/12 – 1.

• using a recognition chart so that the patient may match letters or shapes

• obtaining the services of an interpreter or family member to translate for the patient

• with children, using picture tests such as the Kay picture test and making the procedure into a game – this will usually encourage greater cooperation.

Patients who are in pain should have a drop of topical anaesthetic instilled so that any corneal pain is alleviated and the patient can cooperate more fully with the procedure, thus achieving an accurate visual acuity. Patients sometimes feel that this is a test that they have to pass and ‘cheat’ by looking through their fingers etc. It should be explained that the nurse is attempting to obtain an accurate assessment of their vision and that it is important that they are not tempted to make it seem better than it really is.

Examining the eye

Eye examination must be systematic. It is very easy to assume a diagnosis from the history and, in that way, miss less obvious problems. The eye should be examined from the ‘outside’ – the eye position and surrounding structures – working ‘in’ to consider the globe itself. Considerations for a thorough eye examination are given in Box 31.2.