Ocular Disorder

Robert L. Tomsak

Robert B. Daroff

The differential diagnosis of headache should include primary diseases of the eye and surrounding structures.

The relationships between the eye and headache are multifactorial. The sensory innervation of the eye and periocular region is primarily from the first division of the fifth cranial nerve. Recurrent branches of the trigeminal nerve also supply the intracranial dura, venous sinuses, and cerebral vessels. Thus, headache of nonocular cause is often referred to the eye and orbit, and pain of primary ocular origin commonly radiates to other parts of the head and face.

With few exceptions, primary ocular causes of pain tend to be associated with a red eye. A fundamental maxim is that a “white eye” is rarely the cause of a monosymptomatic painful eye (3), that is, with no other symptoms of visual, oculomotor, or pupillary abnormalities.

HEADACHE ATTRIBUTED TO ACUTE GLAUCOMA

International Headache Society (IHS) code: 11.3.1

ICD-10 code: G44.843

Short description: Glaucoma is a spectrum of eye diseases characterized by damage to the optic nerve, most often associated with increased intraocular pressure (IOP) (16). Only acute primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG) and some forms of secondary glaucoma, associated with either inflammation or neovascularization, are painful, whereas the most common form of glaucoma, primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), is not.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF GLAUCOMA

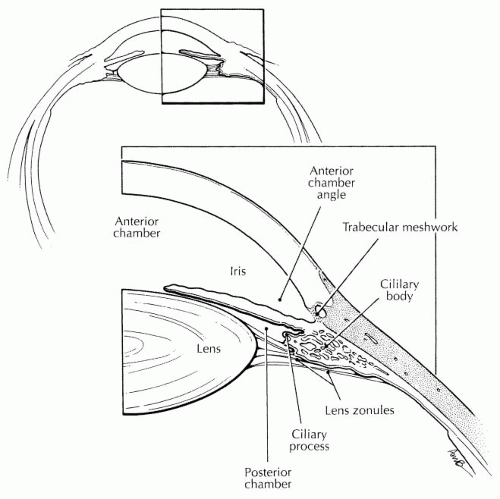

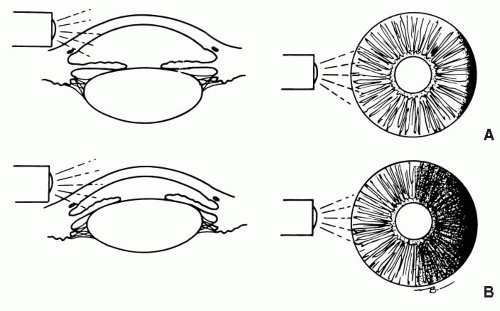

Aqueous humor is produced by the ciliary epithelium of the eye at the root of the iris in the posterior chamber. It then percolates through the pupil to fill the anterior chamber and is drained out of the eye into episcleral veins through the trabecular meshwork (TM) (Fig. 122-1). The TM lies in the angle formed by the intersection of the cornea and the iris. In POAG, the angle is open and the problem of drainage results from abnormalities in the TM, leading to chronic elevations of IOP. In PACG (Fig. 122-2), the filtration angle is more acute than normal and the iris can mechanically obstruct the TM, leading to quadrupling, or more, of the IOP within hours.

Neovascularization of the iris secondary to diabetes mellitus, retinal vascular occlusion, especially central retinal vein occlusion, or chronic inflammation can lead to open or closed angle forms of glaucoma.

In glaucoma secondary to intraocular inflammation, drainage of aqueous humor is impaired by inflammatory debris obstructing the TM or by trabeculitis. In chronic cases of inflammation, neovascularization may be an added factor.

The mechanisms of pain in the secondary glaucomas is multifactorial and include level and rate of rise of IOP, liberation of pain-generating molecules, ciliary muscle spasm, and anterior segment hypoxia.

CLINICAL FEATURES

IHS diagnostic criteria (Revised International Classification of Headache Disorders [ICHD-II]) for headache attributed to acute glaucoma are as follows:

A. Pain in the eye and behind or above it, fulfilling criteria C and D

B. Raised IOP, with at least one of the following:

1. Conjunctival injection

2. Clouding of the cornea

3. Visual disturbances

C. Pain develops simultaneously with glaucoma.

D. Pain resolves within 72 hours of effective treatment of glaucoma.

Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma

Acute angle closure glaucoma is an ophthalmic emergency. The pain becomes severe, boring, and located in and around the eye. Redness of the eye caused by conjunctival and episcleral vessel congestion, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, and diaphoresis may occur. As the pressure elevates, the pupil is often mid-dilated and fixed to light, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of a posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Vision deteriorates initially from corneal edema and may be permanently impaired from anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

Subacute Angle Closure Glaucoma

Subacute angle closure glaucoma (SACG) attacks may be asymptomatic or may present as transient episodes of blurred vision with or without a dull ache around the eye (14). The blurred vision is due to corneal edema and the symptom of colored halos around lights during an attack is quite typical. The SACG attacks occur most frequently in dark environments, because pupillary dilation is the trigger for filtration angle obstruction.

Secondary Glaucomas

The clinical presentation of these conditions is as varied as the disease or syndrome causing them. For example, in glaucomacyclitic crisis (Posner-Schlossman syndrome) the attack is acute or subacute, with pain, ocular redness, and blurred vision lasting hours to days. In neovascular glaucoma accompanying proliferative diabetic retinopathy, the pain is constant, boring, and often severe and can persist for years.

DIAGNOSIS

A definitive diagnosis is made when documenting increased IOP and narrow or blocked filtration angle with gonioscopy. Otherwise, the depth of the anterior chamber angle can be estimated with a hand light (Fig. 122-2)

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis is excellent for PACG if the diagnosis and treatment are accomplished promptly. If not, blindness or severe visual impairment can be expected. The secondary glaucomas have a more variable prognosis, dependent primarily on the underlying disease.

HEADACHE ATTRIBUTED TO REFRACTIVE ERRORS

IHS code: 11.3.2

ICD-10 code: G44.843

Short description: This somewhat controversial subject is best introduced poetically:

“Many patients have complaints That have psychogenic taints—

Blurring, asthenopia,

Occasional diplopia,

Aching brow and heavy lids,

Migraine headaches from the kids.

Although such things befit a ‘crock’

You could become the laughing stock

Because, just possibly, the bearer

Will yield up some refractive error.”

–[Quoted from Milder and Rubin, p. 451 (12)]

CLINICAL FEATURES

IHS diagnostic criteria (ICHD-II) for headache attributed to refractive errors are as follows:

A. Recurrent mild headache, frontal and in the eyes themselves, fulfilling criteria C and D.

B. Uncorrected or miscorrected refractive errors (e.g., hyperopia, astigmatism, presbyopia, wearing of incorrect glasses).

C. Headache and eye pain first develop in close temporal relation to the refractive error, are absent on awakening, and are aggravated by prolonged visual tasks at the distance or angle where vision is impaired.

D. Headache and eye pain resolve within 7 days, and do not recur, after full correction of the refractive error.

The symptoms associated with refractive error are listed in Table 122-1.

Ophthalmologists use the term asthenopia (from the Greek: weakness of sight), or “eyestrain,” to refer to these symptoms. The pain is mild, dull, aching, and often associated with the feeling that the eyes are tired, hot, uncomfortable, sore, or strained.

Only rarely does the patient report “headache.” The exception is the patient with a defined primary headache disorder who notes more frequent headaches after a refractive change. Asthenopic symptoms improve or disappear when the eyes are closed or rested.

TABLE 122-1 Symptoms Suggesting That Refraction Is in Error | ||

|---|---|---|

|

A number of refractive problems are associated with asthenopic symptoms (12). Three common problems are discussed.

Hyperopia, or farsightedness, is a condition where the native optical system of the eye focuses light behind the retina when the eye is trained at a target at an infinite distance. To see clearly, a farsighted person’s lens changes shape by the process of accommodation to become stronger in converging power. Ideally, the accommodation is sufficient to focus light clearly on the retina. Even more accommodation is needed for near work such as reading. People with mild to moderate hyperopia rarely need glasses during their youth. However, if they have significantly uncorrected farsightedness, fatigue of the accommodative mechanism can lead to asthenopia. This problem becomes more bothersome as the aging process causes the human lens to lose its ability to change shape. When accommodation diminishes because of aging to the extent that comfortable focus at near is unable to be sustained, “presbyopia” is said to exist.

Presbyopia begins in the 40- to 50-year age range and becomes symptomatic earlier in an individual with hyperopia. Conversely, myopic, or nearsighted, people usually begin wearing glasses for distance at an early age and may simply remove them when reading after developing presbyopia.

Astigmatism is a condition where the cornea is not spherical but shaped more like an American football. Light is focused in two different planes behind an astigmatic cornea, and an uncorrected astigmat uses accommodation to straddle the planes of focus on the retina to minimize blur. Optical correction for astigmatism collapses the two planes into one, which is then focused on the retina. Asthenopia is often present in uncorrected astigmats. In those who wear corrective lenses for astigmatism, asthenopia becomes a problem if the prescription is changed in large degree or incorrectly. Asthenopic symptoms in astigmats commonly involve perception of visual distortion.

HEADACHE ATTRIBUTED TO HETEROPHORIA OR HETEROTROPIA (LATENT OR MANIFEST SQUINT)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree