Occupational

26-1 Welder’s Flash

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Patients with Welder’s flash (WF) present in a delayed fashion (usually 6 to 12 hours) after welding or observing welding activities. Presenting complaints typically include intensely severe bilateral eye pain, photophobia, lacrimation, blepharospasm, and a gritty or “sandy” feeling or foreign-body sensation of the eyes.1,2

Pathophysiology

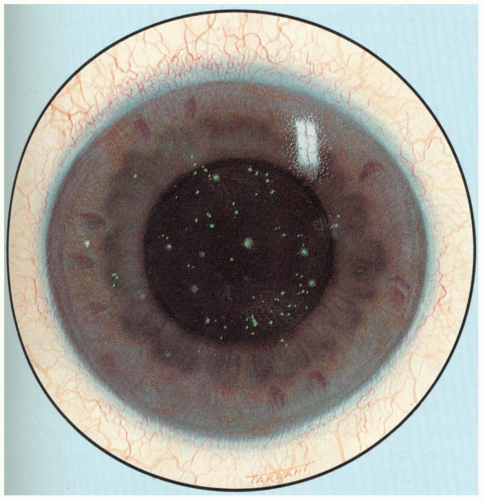

Exposure to UV-B and UV-C radiation may cause a superficial punctate keratopathy that appears several hours after exposure. Welder’s flash is a superficial punctate keratopathy caused by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation related to arc welding. This may be thought of as an ocular analogue of acute blistering sunburn.1,2 WF may be caused by even momentary or peripheral exposure to UV-C during arc welding.1,2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis rests on obtaining a history of exposure to UV-C radiation during welding without appropriate eye protection. Diagnostic confirmation should be obtained by performing slit-lamp microscopy after applying topical anesthetic drops.1,2 Without anesthesia, these patients may not tolerate the slit-lamp examination. The skin of the eyelids and face may be erythematous. The cornea should be stained with fluorescein, which reveals focal loss of epithelial cells in a diffuse, punctate pattern. Symptoms usually disappear within 48 hours, and permanent damage, although possible, is uncommon.

Management

Treatment requires control of blepharospasm with cycloplegic medications. After slit-lamp microscopy under topical anesthesia, the patient’s pain may re-occur. The physician should resist the urge to discharge the patient with a bottle of topical anesthetic, because patients may use this source of temporary relief instead of attending follow-up visits. Some authorities recommend eye patching, but this can be problematic in the bilaterally affected individual.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Wilkenfeld M, Crowley KA, Dawodu O. Occupational eye injury due to phototoxicity. J Occup Environ Med 2002;44:488-489.

2. Tenkate TD. Ultraviolet radiation: human exposure and health risks. J Environ Health 1998;61:9-15.

26-2 Tar and Asphalt Burns

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

The majority of tar and asphalt burns occur in workers who use hot tar or asphalt in the course of their work. Patients present after skin exposure and usually come to the emergency department directly from their worksite.

Pathophysiology

Tar and asphalt are used as protective coatings in various industrial settings, including roofing and road paving. These materials are petroleum distillates with very high boiling points. Because these materials do not cool quickly after being heated, the opportunity exists for prolonged heat transfer to underlying tissues. Because the skin flora is trapped beneath the burn, these injuries are prone to infection. Frequently these burns are associated with vehicular accidents, falls from heights, and explosions, indicating that serious associated multisystem trauma may coexist.1

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually obvious and is based on history and physical examination.

Clinical Complications

Complications include superinfection, associated trauma, and other issues depending on burn location (e.g., hands, eyes, perineum).

Management

Various approaches have been taken, including leaving the tar or asphalt in place to solidify and applying various materials to aid in removal. Proposed removal agents include butter, sunflower oil, De-Solv-it,® neomycin, baby oil, gasoline, mayonnaise, ice, acetone, alcohol, and kerosene.1,2 In any case, removal may be problematic and may take several hours to complete. Sharp débridement for removal is not encouraged because it is painful and may result in the removal of viable underlying skin and skin appendages. Cold water is recommended as a first-aid measure to eliminate the burning process.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Baruchin AM, Schraf S, Rosenberg L, et al. Hot bitumen burns: 92 hospitalized patients. Burns 1997;23:438-441.

2. Turegun M, Ozturk S, Selmanpakoglu N. Sunflower oil in the treatment of hot tar burns. Burns 1997;23:442-445.

26-3 Hydrofluoric Acid Injury

James M. Madsen

Clinical Presentation

Exposure to concentrated hydrofluoric (HF) acid (15% to 20% or greater) can be extremely painful, with vesication and necrosis. More dilute solutions may not cause immediate pain nor become visible for several hours, but they may penetrate deeply and cause subcutaneous blanching, gangrene, and systemic and sometimes fatal electrolyte disturbances, including hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia.1,2

Pathophysiology

Hydrofluoric acid “burns” are more correctly designated as chemical injuries rather than thermal burns. This form of chemical injury is often occupationally related (in those who work with glass, brick, metal, electronics, and reformulated fuels), but may also be related to household rust removers or exposure to HF solutions or vapors. These injuries have special clinical features.

Release of hydronium ions may cause local tissue damage, liquefactive necrosis, severe pain due to potassium release from nerve endings, and hyperkalemia. Systemic effects arise from deep penetration of dilute acid and subsequent release of fluoride ions, which can precipitate calcium and magnesium from soft tissues and bone.1

Diagnosis

A high index of suspicion and a thorough history are important, especially with exposure to more dilute and more penetrating solutions. Identification of HF, its concentration, and other substances in the solution is important, as are clinical and laboratory investigations of serum electrolytes and electrocardiographic monitoring.1,2

Clinical Complications

Gangrenous necrosis of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and even bone may occur, as may secondary infections. Death in fatal cases usually results from disturbances of cardiac rhythm secondary to electrolyte imbalances.1

Management

Prompt skin decontamination should be followed by intermittent application of iced benzalkonium chloride or iced tetracaine benzethonium chloride, which may help alleviate pain. Monitoring of electrocardiographic values and serum electrolytes is mandatory. Calcium gluconate as a topical gel or bath is considered to be only marginally helpful, because these preparations do not penetrate to the deeply involved tissues in an efficient fashion. Subcutaneous injections of calcium preparations are painful and may not penetrate deeply enough. Intravenously or intraarterially administered calcium gluconate is preferred in cases of extensive injury. Topical antibiotic creams may be used prophylactically.1,3

REFERENCES

1. DiLuigi KJ. Hydrofluoric acid burns. Am J Nursing 2001;101:24AAA-24DDD.

2. Elder DS. An accidental acid burn: providing emergency care. Aust Fam Physician 2002;31:37-38.

3. Lin TM, Tsai CC, Lin SD, Lai CS. Continuous intra-arterial infusion therapy in hydrofluoric acid burns. J Occup Environ Med 2000;42:892-897.

26-4 High-Pressure Injection Injury

James M. Madsen

Clinical Presentation

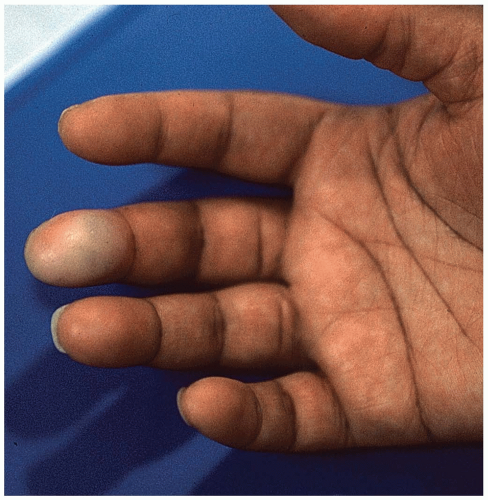

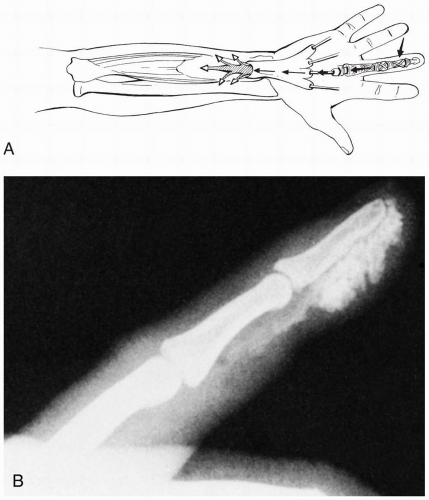

The index finger of the nondominant hand is most frequently affected and displays a deceptively innocuousappearing puncture wound. The worker often underestimates the severity of the injury and continues to work until the later development of excruciating pain and swelling. Injected material may extrude from the injection site or track along the hand and forearm.1,2

Pathophysiology

High-pressure injection injuries typically occur in an industrial setting and may involve grease, paint, hydraulic fluid, diesel fluid, paint thinner, molding plastic, paraffin, cement, dry-cleaning solvents, water, or other substances under high pressure.1

Normally operating high-pressure nozzles deliver pressures of 3,000 to 7,000 pounds per square inch (psi); partial blockage of jets may increase the pressure to 12,000 psi.1 Injected material can cause direct tissue necrosis, and the high pressures may produce ischemia from tissue distention. Secondary bacterial infection may occur in devitalized tissue.2

Diagnosis

Clinical Complications

Management

Prompt presentation and early clinical recognition are vital.1 Tetanus immunization should be given as indicated, and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given prophylactically via the intravenous route while the patient is still in the emergency department.1 Emergency department management with local incision and drainage is not appropriate, because these injuries require wide surgical exploration (including tendon sheaths and other deep structures) in the operating theater, with aggressive irrigation and débridement. The examining physician may be tempted to simply express whatever fluid was injected, by the application of lateral pressure to the wound margins. This practice is mentioned only so that it may be completely condemned as being inappropriate.2 In some cases, amputation of the affected part and/or extensive physical rehabilitation are necessary.

REFERENCES

1. Schnall SB, Mirzayan R. High-pressure injection injuries to the hand. Hand Clin 1999;15:245-248.

2. Gutowski KA, Chu J, Choi M, et al. High-pressure hand injection injuries caused by dry cleaning solvents: case reports, review of the literature, and treatment guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;111:174-177.

26-5 Hypothenar Hammer Syndrome

Michael Greenberg

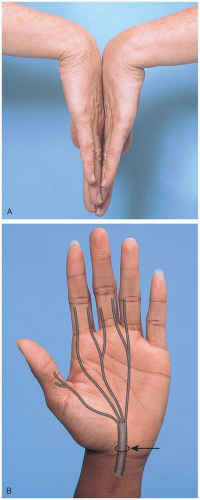

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

Hypothenar hammer syndrome (HHS) is a syndrome involving unilateral digital ischemia caused by digital artery occlusions. This is a result of embolization from the palmar artery, caused by the repeated use of the palmar surface of the hand as a blunt force “tool.”1,2,3

The pathophysiology of this injury requires direct, forceful, and repeated trauma to the palm of the hand. It is theorized that embolic occlusion of the digital and other small arteries in the hand may originate from a damaged or thrombosed palmar ulnar artery, resulting from this mechanism of injury. Fibromuscular dysplasia is evident in the affected ulnar arteries.2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on a history of repeated direct trauma to the palmar surface of the hand. This usually occurs in an occupational setting with the use of the hand to align lumber, hammer, or drive materials together. However, this mechanism of injury may also occur in hobbyists and in people who engage in carpentry or similar work as an avocation.1,2,3 HHS also occurs in baseball catchers, when the hand is repeatedly subjected to impact from catching a hard-thrown ball. A unilateral Raynaud’s phenomenon that spares the thumb and feet may be manifest, and in some cases a palmar mass is evident.1,2 The diagnosis is verified by angiography. Recently, ultrasound has been used to demonstrate ulnar artery thrombosis in HHS.3

Clinical Complications

Complications include the development of aneurysmal dilatation of the ulnar artery, as well as embolic damage to the distal digits that is part and parcel of the HHS itself.

Management

Therapeutic interventions may include oral sympatholytic drugs (phenoxybenzamine, reserpine, calcium-channel blockers), stellate ganglion blockade, local thrombolysis, microvascular surgical reconstruction, and sympathectomy. In addition, patients should be counseled to cease using the hand as a hammering tool and to reduce vascular effects by smoking cessation. Patients identified in the emergency department should be appropriately counseled and referred to an orthopedic or plastic surgeon who specializes in hand surgery.

REFERENCES

1. Wong GB, Whetzel TP. Hypothenar hammer syndrome: review and case report. Vasc Surg 2001;35:163-166.

2. Ferris BL, Taylor LM Jr, Oyama K, et al. Hypothenar hammer syndrome: proposed etiology. J Vasc Surg 2000;31:104-113.

3. Dean Okereke C, Knight S, McGowan A, Coral A. Hypothenar hammer syndrome diagnosed by ultrasound. Injury 1999;30:448-449.

26-6 Vibration-Related Disorders

James M. Madsen

Clinical Presentation

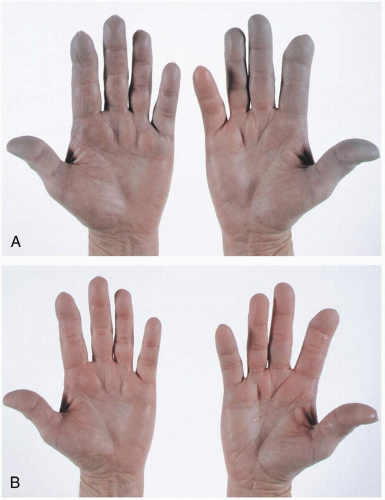

Whole-body vibration, usually between 5 to 30 frequency, occurs in commercial-vehicle drivers and others and may manifest as vision problems and low-back pain.2 Segmental vibration of 200 to 500 Hz affects the upper extremities, resulting in attacks of Raynaud’s-like sensorineural (neurologic) and vascular impairment lasting from 15 minutes to 2 hours.1

Pathophysiology

Vibration-related disorders include adverse health effects from whole-body or segmental vibration. The most well-defined clinical entity associated with vibration is hand-arm vibration syndrome (HAVS), which is also known as Raynaud’s phenomenon of occupational origin.1 It was previously called vibration white fingers.

Segmental vibration is postulated to induce overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system or a local digital vascular fault. Either way, vasoconstriction of digital arteries leads to an altered “hunting reaction” characterized by hypoperfusion of the fingers followed by vasodilatation, although the vasodilatation may be minimal in HAVS.1

Diagnosis

Aids in the diagnosis of HAVS include history (onset may be as rapid as 3 months), cold-provocation testing involving observation of finger color and measurement of finger systolic blood pressure, nerve-conduction studies, and vibrometry testing. The Stockholm scale establishes separate grading criteria for the vascular and neurologic manifestations of the disease.1,2

Clinical Complications

HAVS may occur concurrently with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and can mimic it; whether CTS may develop as a complication of HAVS is still unclear.3 There also appears to be an association between HAVS and hearing loss.

Management

Avoidance or minimization of vibration, including work transfer as needed, is the mainstay of treatment for HAVS. Maintenance of core and hand temperature is helpful, as is night splinting. Medications include calcium-channel blockers and, to reduce platelet deposition, pentoxifylline. Surgical release of the flexor retinaculum may help associated CTS but does not alleviate vascular symptoms.3

REFERENCES

1. Issever H, Aksoy C, Sabuncu H, et al. Vibration and its effects on the body. Med Princ Pract 2003;12:34-38.

2. Olsen N. Diagnostic aspects of vibration-induced white finger. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2002;75:6-13.

3. Falkiner S. Diagnosis and treatment of hand-arm vibration syndrome and its relationship to carpal tunnel syndrome. Aust Fam Physician 2003;32:530-534.

26-7 Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

James M. Madsen

Clinical Presentation

Pain, numbness, and tingling in the distribution of the median nerve are classic symptoms, but numbness involving all of the fingers may be more common. Symptoms are usually worse at night and may awaken patients from sleep.1 Pain and paresthesias may radiate up to the shoulder, and decreased grip strength may progress to atrophy of the thenar musculature.1

Pathophysiology

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a focal peripheral neuropathy that involves compression of the carpal tunnel in the wrists and resulting compression of the median nerve.

Compression of the carpal tunnel probably causes pain by neural ischemia rather than physical damage to the nerve. The compression may result from edema, which is associated with repetitive motion or with a number of concurrent conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, various rheumatologic and inflammatory diseases, obesity, and acute trauma.3

Diagnosis

History is important. Phalen’s test and Tinel’s sign are positive in many hand conditions. Magnetic resonance imaging is reasonably discriminatory, unlike plain radiography. Electromyography and nerve-conduction studies are plagued by false-positive and false-negative findings; they are most useful for confirming the diagnosis in suspected cases and for excluding neuropathy and other nerve entrapments.2

Clinical Complications

Chronic hand pain, paresthesias, and weakness may lead to long-term disability, especially in workers with severe symptoms. Iatrogenic injury to the median nerve may occur during attempts to inject corticosteroids into the carpal tunnel.

Management

Ergonomic counseling and modifications of work practices may minimize precipitating factors, as may treatment of coexisting related disorders. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications (NSAIDs) and pyridoxine have not been demonstrated to be helpful, but splinting, corticosteroid injections into the carpal tunnel, and, in refractory cases, surgical carpal-tunnel release are beneficial.2

REFERENCES

1. Viera AJ. Management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:265-272.

2. Katz JN, Simmons BP. Clinical practice: carpal tunnel syndrome. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1807-1812.

3. Atcheson SG, Ward JR, Lowe W. Concurrent medical disease in work-related carpal tunnel syndrome. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1506-1512.

26-8 Occupational Irritant Contact Dermatitis

James M. Madsen

Clinical Presentation

Typically, occupational irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is localized, affects workers who have a predisposition to atopy, has a latent period ranging from minutes or hours (with strong irritants) to months (with weak irritants), is characterized by red and scaling fissures, is photopatch negative, and may be chronic.1 Workers with prolonged exposure to water or to chemicals in solution are particularly at risk.1,2,3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree