Obstetrics

13-1 Pelvic Ultrasonography

Anthony Morocco

Pelvic ultrasonography has become a valuable tool for the evaluation of lower abdominal pain and pregnancy-related pathology in the emergency department.

Pelvic sonograms may be performed by a transabdominal (TAS) or an endovaginal (EVS) approach. TAS allows a wider view of the pelvis and more superior structures, and it is less invasive. The advantages of EVS are greater resolution and better visualization of the uterus and adnexal structures, better visualization of a uterus that is retroverted or affected by large fibroids, no requirement for a full bladder, and better imaging in obese patients.1

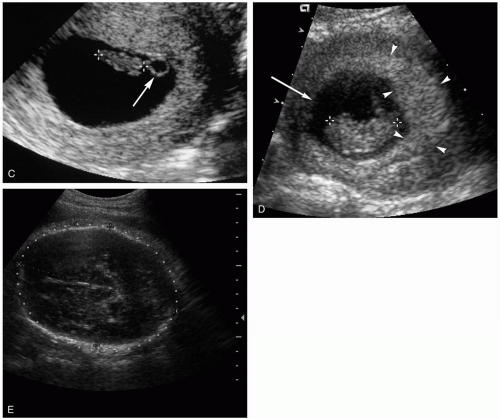

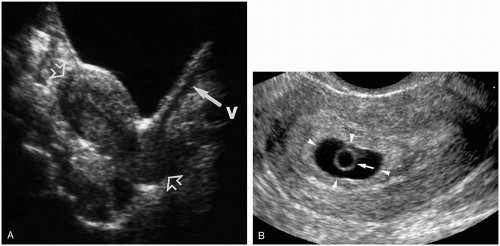

Ultrasonography in the first trimester of pregnancy is useful for assessing fetal viability and ectopic pregnancy. A gestational sac can first be visualized by EVS at 4.5 weeks of gestational age and by TAS 7 to 10 days later. The true gestational sac is visualized as a double decidual sac, with an anechoic center surrounded by two echogenic concentric rings. At 5 to 6 weeks, the yolk sac is seen, followed by the fetal pole. Cardiac activity is visualized by EVS at 6 weeks of gestational age.1

Patients with bleeding or pain early in pregnancy can be evaluated for a number of findings, including fetal viability, location of pregnancy, retained products after incomplete abortion, and molar pregnancy. For ectopic pregnancy evaluation, evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) should be present on EVS if the serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentration is greater than approximately 1,500 to 2,000 mIU/mL. Findings consistent with ectopic pregnancy include lack of a definite IUP with this concentration of hCG and the presence of an adnexal mass, viable ectopic gestation, free fluid in the pelvis, and adnexal tenderness with probe pressure.1

FIGURE 13-1 A: Normal sagittal pelvic ultrasonogram. (From Sauerbrei, with permission.) B: Gestational sac. (From Doubilet and Benson, with permission.) |

Ultrasonography can diagnose a number of problems in the third trimester of pregnancy, including placenta previa, placental abruption, and traumatic injuries (e.g. abruption, uterine rupture).1

Several other diagnoses may be confirmed by pelvic ultrasound when evaluating lower abdominal pain. Tubo-ovarian abscess is diagnosed by visualization of a thickened, fluid-filled fallopian tube. Various types of cysts can be visualized in the ovaries, and free fluid in the pelvis may be indicative of cyst rupture. Color-flow Doppler ultrasonography may reveal an enlarged ovary with decreased blood flow in ovarian torsion.1

REFERENCES

1. Phelan MB, Valley VT, Mateer JR. Pelvic ultrasonography. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1997;15:789-824.

13-1 Pelvic Ultrasonography

Anthony Morocco

13-2 Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Jennifer Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

Patients with preeclampsia typically present in the third trimester of pregnancy with hypertension and proteinuria, accompanied by any or all of the following: nondependent edema, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, headache, and visual disturbances. Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet concentration are sometimes seen; these abnormalities are the hallmark of the HELLP syndrome, a subtype of preeclampsia. Rarely, a patient presents after or during an eclamptic seizure.1

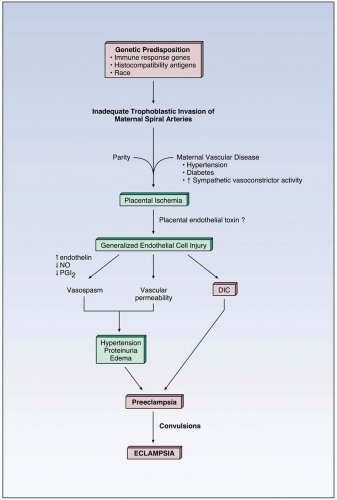

Pathophysiology

Preeclampsia is a syndrome specific to pregnancy that is defined by hypertension (140/90 mm Hg or higher) and proteinuria (0.3 g or greater per 24 hours), with onset occurring after 20 weeks of gestation. Eclampsia is defined as the syndrome of new-onset seizures occurring in a patient who has been diagnosed with preeclampsia.1 Preeclampsia is estimated to occur in 5% to 8% of pregnancies, with approximately 1% of those cases progressing to eclampsia.2 The cause of preeclampsia is unknown; however, vascular changes occur that result in vasospasm and endothelial damage. This leads to hypertension, edema, and end-organ damage.1 Risk factors for preeclampsia include primiparity, multiple gestations, prior preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, autoimmune disease, pregestational diabetes, nephropathy, obesity, age older than 35 years, and African-American race.1

Diagnosis

Because the presenting complaints for preeclamptics are often vague, the physician must have a high index of suspicion. Blood pressure assessment suggests the diagnosis, at which point a urine dipstick for protein can quickly be performed (1 + or greater is suspicious). Liver enzymes, complete blood count, and lactate dehydrogenase or peripheral blood smear are abnormal in patients exhibiting the HELLP variant. In those presenting with seizures, other causes should be ruled out, including arteriovenous malformations, ruptured aneurysm, and idiopathic seizure disorder.1

Clinical Complications

The hypertension, vasospasm, and endothelial damage that occur with preeclampsia can result in numerous adverse outcomes. Cerebral edema and herniation, intracranial hemorrhage, renal failure, subcapsular hepatic hematoma and capsule rupture, and pulmonary edema all contribute to maternal mortality. Fetal morbidity and mortality arise from placental abruption, premature delivery, and growth restriction.1

Management

The cure for preeclampsia is delivery; however, the mode and timing of delivery must be individualized. Obstetric consultation should be obtained as soon as possible, with transfer to a tertiary care facility for the preterm gestation. If gestation is less than 34 weeks, corticosteroids should be administered to promote lung maturity in the event of delivery. For the patient with eclampsia, control of blood pressure and seizure activity is paramount. Diastolic blood pressures greater than 105 to 110 mm Hg should be treated with parenteral antihypertensives; labetalol and hydralazine have both been extensively studied.1 Prospective, randomized controlled trials have validated magnesium sulfate as the drug of choice for eclamptic seizures, and it can be given intravenously or intramuscularly.2,3

REFERENCES

1. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:159-167.

2. Witlin AG. Prevention and treatment of eclamptic convulsions. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1999;42:507-518.

3. Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the Collaborative Eclampsia Trial. Lancet 1995;345:1455-1463.

13-2 Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Jennifer Hendrickson

13-3 Melasma (Mask of Pregnancy)

Jennifer Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

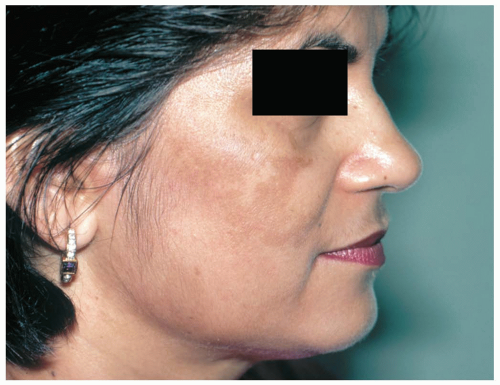

Women with melasma typically present during pregnancy with patchy, darkened, macular lesions of the cheeks, forehead, and upper lip. The neck and forearms can also be affected, but lesions are limited to sun-exposed areas.1

Pathophysiology

Melasma is an acquired disorder that results in a blotchy hyperpigmentation of the face. It is most frequently seen in pregnant women, earning the name “mask of pregnancy,” but can also be seen in women who use oral contraceptives or phenytoin.1 Although the exact cause of melasma is unknown, a genetic predisposition appears to exist.1 Ultraviolet (UV) exposure and sex steroids, particularly progesterone, appear to be key mediators.1 Melanin deposition can occur in either the dermal or the epidermal layer; only the epidermal variant is responsive to topical bleaching agents. The hyperpigmentation tends to increase as the pregnancy progresses, with some regression once delivery occurs. Some or all of the pigmentation may be permanent.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made on physical examination. Differentiation of dermal from epidermal melasma is important when considering therapy, because dermal melasma does not respond to bleaching agents. A Wood’s lamp examination that accentuates the demarcation between normal and hyperpigmented skin suggests epidermal melasma. Differential diagnosis includes erythematic dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis), postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and vitiligo of the surrounding area.

Clinical Complications

Melasma is strictly a cosmetic alteration. Sensitivity to treatment modalities can result in a worsening of the appearance due to hypersensitivity pigmentation.

Management

Although no treatment is needed in the emergency department, the patient may be informed that avoidance of UV light and liberal use of sunscreen that blocks UV-A and UV-B are first-line therapies. Bleaching regimens are useful for epidermal melasma; however, these are usually reserved for the postpartum period. Laser therapy and chemical peels have also been used.

REFERENCES

1. Halder R, Nandedkar M, Neal K. Pigmentary disorders in ethnic skin. Dermatol Clin 2003;21:617-627.

13-4 Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Marisa Stumpf

Jacob W. Ufberg

Clinical Presentation

Women with hyperemesis gravidarum may present with intractable vomiting in the first trimester of pregnancy. Although nausea and vomiting are common in early pregnancy (50% to 90%), patients with hyperemesis gravidarum (approximately 0.5%) have persistent, intractable vomiting and may develop weight loss, dehydration, metabolic acidosis and alkalosis, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hypokalemia.1,2 Symptoms usually begin at 5 to 6 weeks of gestation, peak at 9 weeks, and abate by 16 to 18 weeks. However, a small percentage of patients continue to have symptoms until delivery.1

Pathophysiology

Hyperemesis gravidarum is a syndrome characterized by intractable vomiting during pregnancy. The cause of hyperemesis gravidarum is unknown and is most likely multifactorial. Several hormones have been implicated (e.g., β-human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG], estradiol, 17-hydroxyprogesterone) because their concentration peaks as the incidence of hyperemesis gravidarum peaks; however, no cause-and-effect relationship has been established.1 The thyroid hormone concentration may be higher in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum, most likely from an effect of particular subtypes of hCG on the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor. Other possible factors include altered gastrointestinal motility, hepatic function, lipid metabolism, and psychological issues.1

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be made clinically. Laboratory findings may include ketonemia, ketonuria, elevated hematocrit, and elevated blood urea nitrogen. Hyperemesis gravidarum leads to elevations in liver enzymes in 40% of patients who are hospitalized with hyperemesis.2 The differential diagnosis includes gastroenteritis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, peptic ulcer, pyelonephritis, and fatty liver of pregnancy.

Clinical Complications

Clinical complications are related to vomiting (weight loss, syncope, dehydration, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, Mallory-Weiss tears).

Management

Management consists of adequate fluid resuscitation, correction of acid-base and electrolyte abnormalities, and thiamine supplementation.2 Patients with mild symptoms may require only rehydration and antiemetics (oral and suppository) on discharge. Patients with severe symptoms may require intravenous antiemetic and fluid therapy. Patients who are unable to tolerate oral hydration should be admitted to the hospital. The antiemetics, including metoclopramide, promethazine, prochlorperazine, chlorpromazine, and ondansetron, are all effective and there are no data to support one over another.2 Oral corticosteroids may also be effective in decreasing the frequency of vomiting.2

REFERENCES

1. Eliakim R, Abulafia O, Sherer DM. Hyperemesis gravidarum: a current review. Am J Perinatol 2000;17:207-218.

2. Goodwin TM. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998; 41:597-605.

13-5 Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques of Pregnancy

Jennifer Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, known as PUPPP, arises most often in the third trimester, with a mean onset at 35 weeks. Eruptions are polymorphous, typically arising from the abdominal striae and spreading to the rest of the trunk and extremities. Patients report rapid onset of intense pruritus that spontaneously resolves shortly after delivery.1

Pathophysiology

PUPPP is the most common dermatologic disorder specific to pregnancy. PUPPP affects 1 of every 130 to 300 pregnancies, occurring most frequently in primigravidas and those with multiple gestations.2 The exact pathophysiology of PUPPP is not clearly defined; some researchers have postulated rapid abdominal distention as a causative factor, whereas the presence of fetal DNA in PUPPP skin lesions has caused others to propose an immune-mediated etiology.2

Diagnosis

PUPPP is mainly a diagnosis of exclusion, because there are no laboratory abnormalities or histopathologic findings specific to this condition. The differential diagnosis includes viral exanthems, drug rashes, herpes gestationis, and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP).1 Because of the adverse fetal effects associated with ICP, bile acids should be measured to rule out this diagnosis.

Clinical Complications