Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

Jane C. Ballantyne

Steven A. Barna

Take an aspirin and call me in the morning.

—Twentieth-century physician

The nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, are the most widely used analgesics in the United States and worldwide. Although they are considered weak analgesics, NSAIDs are used for the treatment of headaches, menstrual cramps, arthritis, and a wide range of minor aches and pains. NSAIDs have also become popular for use in the surgical population, especially since the advent of injectable preparations. Because of their predominantly peripheral site of action, they are useful in combination with opioids and other centrally acting analgesics for severe pain, both acute and chronic. This chapter reviews the use of NSAIDs for acute and chronic pain—indications, efficacy, side effects, and contraindications.

I. PHARMACOLOGY

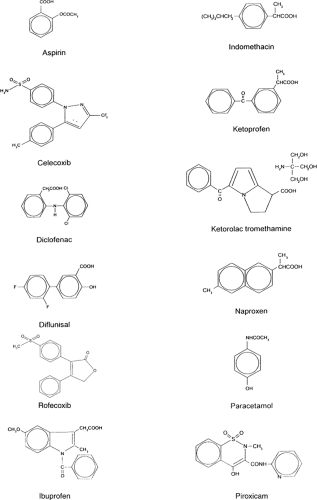

The NSAIDs are a heterogeneous group of compounds consisting of one or more aromatic rings connected to an acidic functional group (see Fig. 1). The chemical families of the commonly used NSAIDs are outlined in Table 1. The NSAIDs are weak organic acids (pKa 3 to 5.5), act mainly in the periphery, bind extensively to plasma albumin (95% to 99% bound), do not readily cross the blood–brain barrier, are extensively metabolized by the liver, and have low renal clearance (<10%). Acetaminophen is not strictly an antiinflammatory drug but is included in this group of drugs because it shares many of the properties of the NSAIDs. In contrast to the true NSAIDs, acetaminophen is nonacidic, is a phenol derivative, and readily crosses the blood–brain barrier. It acts mainly in the central nervous system, where prostaglandin inhibition produces analgesia and antipyresis. Its peripheral and antiinflammatory effects are weak.

Table 1. Classification of commonly used antipyretic analgesics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

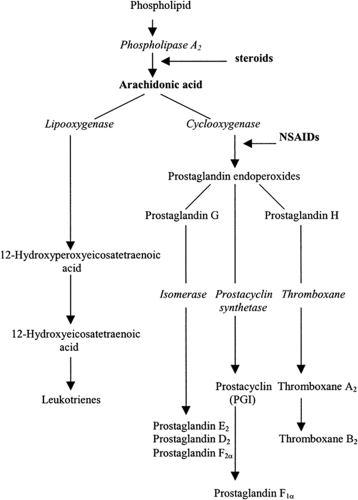

NSAIDs are powerful inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis through their effect on cyclooxygenase (COX) (see Fig. 2). Prostaglandins have many effects, and the therapeutic and toxic effects of NSAIDs can be accounted for by the ability of these drugs to inhibit prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis (see Table 2). Prostaglandins themselves are not thought to be important pain mediators, but they do cause hyperalgesia by sensitizing peripheral nociceptors to the effects of various mediators of pain and inflammation such as somatostatin, bradykinin, and histamine. Therefore, NSAIDs primarily treat hyperalgesia or secondary pain, particularly the pain resulting from inflammation.

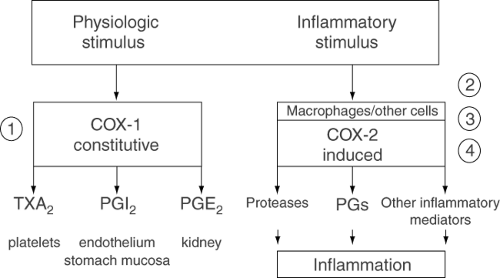

Two isoforms of COX have been recognized: an inducible isoenzyme (COX-2) and the constitutive enzyme (COX-1). COX-1 is expressed in most tissues under physiologic conditions, whereas COX-2 is induced by mediators of inflammation under pathologic conditions (see Fig. 3). COX-1 has a protective effect in the stomach because it is the source of prostaglandins E2 and I2, which are cytoprotective in the gastrointestinal epithelium. COX-2 is the source of the same prostaglandins in the mediation of inflammation.

A new subclass of NSAIDs has recently been released for clinical use—the selective COX-2 inhibitors, known also as coxibs. These drugs were developed in the hope of being able to reduce

NSAID side effects, particularly the damaging gastrointestinal (GI) effects. The first drugs (celecoxib and rofecoxib) became available in the United States in 1999; valdecoxib followed more recently. Early clinical trials and clinical experience confirmed the analgesic efficacy and favorable side-effect profile of these drugs with regard to their effects on the gastric mucosa and on platelets, although some of the early trial results have now been brought into question. Coxibs do not seem to have any advantage in terms of renal effects, and serious concerns have arisen over a

possible increase in the risk of myocardial infarction and thrombotic stroke when coxibs are taken continuously for long periods. In 2004, the manufacturers of rofecoxib withdrew the drug from the market because new trials substantiated the fears of adverse cardiovascular effects. Similar concerns arose in connection with the other coxibs, and in 2005 valdecoxib was also withdrawn. The coxibs will be used with greater caution now that their cardiovascular (and other) risks are better understood.

NSAID side effects, particularly the damaging gastrointestinal (GI) effects. The first drugs (celecoxib and rofecoxib) became available in the United States in 1999; valdecoxib followed more recently. Early clinical trials and clinical experience confirmed the analgesic efficacy and favorable side-effect profile of these drugs with regard to their effects on the gastric mucosa and on platelets, although some of the early trial results have now been brought into question. Coxibs do not seem to have any advantage in terms of renal effects, and serious concerns have arisen over a

possible increase in the risk of myocardial infarction and thrombotic stroke when coxibs are taken continuously for long periods. In 2004, the manufacturers of rofecoxib withdrew the drug from the market because new trials substantiated the fears of adverse cardiovascular effects. Similar concerns arose in connection with the other coxibs, and in 2005 valdecoxib was also withdrawn. The coxibs will be used with greater caution now that their cardiovascular (and other) risks are better understood.

Table 2. Prostaglandin and thromboxane actions | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Figure 3. Relation between the pathways leading to the generation of prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and other eicosanoids by COX-1 or COX-2. |

Table 3. Principal adverse effects of long-term NSAID therapy | |

|---|---|

|

II. ADVERSE EFFECTS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Unfortunately, the NSAIDs are not free of bothersome, and sometimes even dangerous, adverse effects (see Table 3). Many patients cannot tolerate these drugs because of their GI effects. Surveys suggest that more than 100,000 patients are hospitalized and 16,500 die each year in the United States secondary to NSAID-associated GI events, the elderly being particularly affected.

1. Gastrointestinal Effects

Prostaglandins inhibit acid secretion by blocking the activation of parietal cells by histamine. At the same time, prostaglandins are cytoprotective because they stimulate mucus production from the upper GI tract. By inhibiting prostaglandins, NSAIDs cause gastroduodenal mucosal lesions and ulcers. Gastritis, resulting in abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and, sometimes, diarrhea, is an extremely common side effect of NSAIDs that occurs particularly in persons with a propensity to peptic ulceration and that occasionally results in catastrophic GI bleeding and death. Upper GI studies demonstrate a 15% to 30% prevalence of ulcers in the stomach or duodenum of patients taking NSAIDs regularly (see Table 4). Symptomatic ulcers and ulcer complications associated with the use of standard NSAIDs may occur in 1% of patients treated for 3 to 6 months and in 2% to 4% of patients treated for 1 year. Eighty percent of patients with GI toxicity have no preceding symptoms and most have few or no risk factors.

Table 4. Cumulative prevalence of endoscopically visualized ulcers after 12 weeks of therapy with various NSAIDs (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

It is accepted practice to withhold NSAIDs from patients with known peptic ulcer disease. The risk of GI toxicity can be scored using the ARAMIS (Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information System) scoring system (see Table 5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree