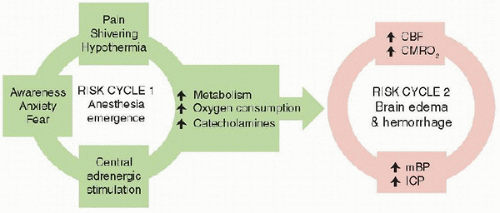

The general goal of anesthetic management is to maintain stable hemodynamics and adequate gas exchange while providing analgesia and, when needed, sedation. In neuroanesthesia, this translates to maintenance of oxygenation, provision of appropriate carbon dioxide levels, preservation of adequate cerebral blood flow (

CBF), and avoidance of exacerbations of intracranial hypertension. Hyponatremia, hypo-osmolarity, and hyperglycemia can contribute to cerebral swelling and neurological injury and are avoided. Anesthetic agents and depth are managed so as to permit a crisp wakeup and immediate neurological assessment once surgery is complete. Despite these seemingly straightforward goals, hypotension (

1), hyperglycemia (

2), and inadvertent hyperventilation (

3) are persistent, but modifiable, risk factors in the perioperative period.

Induction of anesthesia usually involves premedication followed by titration of intravenous or inhaled agents at a rate that minimizes the hemodynamic consequences of transition from waking to anesthetic states. Premedication is administered with caution to avoid respiratory depression and is often avoided when significant intracranial hypertension is present. Induction agents are carefully titrated to avoid hypotension and decreased

CBF. Thiopental (not available in United States), propofol, etomidate, and ketamine are common induction agents, and their effects on blood pressure (

BP), intracranial pressure (

ICP),

CBF, and cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen (

CMRO2) are considered prior to use. Recently, concerns about these deleterious effects of ketamine have been questioned (

4,

5). To minimize vasodilation that accompanies volatile agents, anesthetic maintenance classically involves a “balanced” technique using nitrous oxide, a narcotic, and lowdose volatile agent. The effect of volatile agents on

CBF can vary with the dose of agent (increased vasodilation at higher dose), the region of brain studied (more pronounced on surface vessels), and the use of hyperventilation to cause vasoconstriction (often requested by neurosurgeons, to shrink brain tissue, even when

ICP is normal). All volatile agents cause dose-dependent increases in

CBF that can be attenuated with controlled ventilation. There is longstanding debate around the use of nitrous oxide since it can cause some degree of cerebral vasodilation, it may contribute to postoperative vomiting,

as well other limitations (

6). In addition, nitrous oxide is relatively contraindicated when air collections are present (such as after recent craniotomy) since its diffusion may cause their expansion. Increasingly, there is addition or substitution of ultrashortacting agents such as remifentanil or dexmedetomidine for anesthetic maintenance. The general effects of commonly used anesthetics on

CMRO2,

CBF, pressure autoregulation, and

ICP are summarized in

Table 60.1.

The PICU should be considered an extension of the neurosurgical operating room and interventional neuroradiology suite. As such it is imperative that all practitioners in the continuum of perioperative care communicate plans, concerns, and strategies.

The PICU should be considered an extension of the neurosurgical operating room and interventional neuroradiology suite. As such it is imperative that all practitioners in the continuum of perioperative care communicate plans, concerns, and strategies. It is important to have familiarity with current and potential neuromonitoring for children with neurosurgical and cerebrovascular disease.

It is important to have familiarity with current and potential neuromonitoring for children with neurosurgical and cerebrovascular disease. It is important to be cognizant of special problems that occur in this population in the postoperative period, in particular the dysnatremias.

It is important to be cognizant of special problems that occur in this population in the postoperative period, in particular the dysnatremias. neuroradiology suite and continues through the PICU. In addition, good patient care often requires the intensivist to provide expertise outside the PICU, in the emergency department, the radiology suite, and even into general or rehabilitative care settings. It is important, therefore, for a critical care physician to maintain a “systems” perspective and good working knowledge of the specialties and practices comprising this continuum of care. The focus of this chapter is upon close coordination of neurosurgery, neuroradiology, anesthesia, and critical care practices in this population of critically ill children. We begin with an overview of considerations important to our colleagues in anesthesiology, neurosurgery, and neuroradiology; continue with discussion of routine postoperative care; and then proceed with more detailed discussion of specific surgical entities. We conclude with discussion of a few specific postoperative challenges that are common in neurointensive care.

neuroradiology suite and continues through the PICU. In addition, good patient care often requires the intensivist to provide expertise outside the PICU, in the emergency department, the radiology suite, and even into general or rehabilitative care settings. It is important, therefore, for a critical care physician to maintain a “systems” perspective and good working knowledge of the specialties and practices comprising this continuum of care. The focus of this chapter is upon close coordination of neurosurgery, neuroradiology, anesthesia, and critical care practices in this population of critically ill children. We begin with an overview of considerations important to our colleagues in anesthesiology, neurosurgery, and neuroradiology; continue with discussion of routine postoperative care; and then proceed with more detailed discussion of specific surgical entities. We conclude with discussion of a few specific postoperative challenges that are common in neurointensive care. that will optimize outcome.

that will optimize outcome.