CHAPTER 28 NEUROPATHIC PAIN

2. Why do the definitions of neuropathic pain, nociceptive pain, and psychogenic pain refer to these disorders as “inferred” pathophysiologies?

5. The clinical diversity of neuropathic pain suggests that the mechanisms responsible are both numerous and complex, presumably involving interactions between the PNS and CNS. Is there a useful model for conceptualizing these interacting mechanisms?

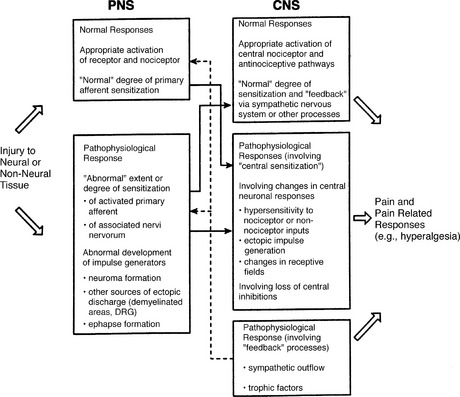

Three decades of basic research have shown that neuropathic pain may result from any of a variety of mechanisms that interact in complex ways. The normal response of the PNS and the CNS following exposure to a noxious stimulus can become disturbed at multiple levels concurrently (Fig. 28-1). This process may involve altered peripheral input (e.g., from sensitization of primary afferent neurons) or central processing (e.g., any of the mechanisms involved in so-called central sensitization; see Question 9), changes in efferent activity in the sympathetic nervous system, and shifts in pain modulatory processes in both the PNS and CNS. Further research is needed to determine the specific processes that result in these pathologic distortions of normal nociception.

6. From the clinical perspective, what is a useful classification of the heterogeneous population with chronic neuropathic pain?

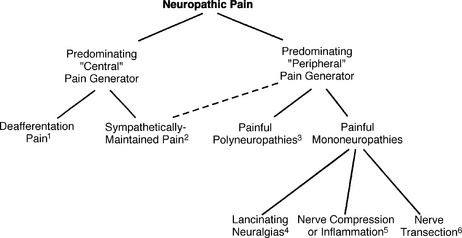

Although patients with neuropathic pain are traditionally categorized on the basis of diagnosis (e.g., painful diabetic polyneuropathy) or site of the precipitating lesion (e.g., peripheral nerve), it may be most useful to extend the classification based on inferred pathophysiology, and to suggest that some patients with neuropathic pain have disorders that are primarily sustained by processes in the CNS, whereas others have disorders sustained by processes in the PNS. This distinction is suggested by both clinical and experimental data (Fig. 28-2). For example, a predominant peripheral pathophysiology is suggested by the observation that some patients with neuropathic pain precipitated by nerve injury are cured by a local intervention, such as resection of a neuroma. A predominant central pathophysiology is obvious in those patients whose neuropathic pain is precipitated by stroke.

7. What neuropathic pain syndromes are presumably sustained by aberrant somatosensory processing in the CNS?

Neuropathic pains that are inferred to have sustaining mechanisms in the CNS can be broadly divided into two groups: (1) disorders known as the deafferentation pains, and (2) disorders collectively known as complex regional pain syndromes (previously known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy and causalgia; see Question 50). The deafferentation pains include a large number of specific syndromes, such as central pain (pain following injury to the CNS), pain resulting from avulsion of a plexus, pain resulting from spinal cord injury, postherpetic neuralgia, phantom pain, and others. Complex regional pain syndrome is presumably sustained by a number of different mechanisms. One such mechanism is believed to involve efferent activity in the sympathetic nervous system and produces a pain known as sympathetically maintained pain.

8. Which pain syndromes are presumably sustained by aberrant somatosensory processing in the peripheral nervous system?

9. Describe the specific CNS mechanisms likely involved in the various types of deafferentation pain

Central sensitization may involve functional and structural changes in CNS pathways involved in nociception (see Fig. 28-1 and Table 28-1). Each of these changes presumably occurs as a consequence of specific mechanisms, which have only begun to be elucidated. Recent studies, for example, have indicated the importance of an interaction between excitatory amino acids (specifically glutamate) and the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in producing sensitization of nociceptive neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Although the relationship of these functional and structural changes to chronic pain in humans is conjectural, the range of phenomena underscores the plasticity of central connections and suggests a focus for future research targeted at the prevention or treatment of neuropathic pain.

TABLE 28-1. Changes that may be Involved in Neuropathic Pains Sustained by Abberrant Processes in the Central Nervous System

| Functional Changes | Structural Changes |

|---|---|

| Lowered threshold for activation | Transsynaptic degeneration |

| Exaggerated activation | Transganglionic degeneration |

| Ectopic discharges | Collateral sprouting |

| Enlarging receptive fields | |

| Loss of normal inhibition |

10. Phantom pain is commonly considered to be a type of deafferentation pain. What is phantom pain?

Although the prototype phantom pain follows limb amputation, the term is applied to pain following amputation of any body part. For example, surveys have described phantom pain following mastectomy and tooth extraction. Some authors also use the term to describe pain in regions of the body that are completely denervated (rendered anesthetic) but not amputated, such as the area below a transected spinal cord or the area supplied by a severely injured peripheral nerve. This usage may be confusing, however, and it would be preferable to use the term “central pain,” or one of its subtypes (see Question 35), to describe a pain that occurs in an area denervated as a result of a CNS lesion, and to use either the generic term “deafferentation pain” or the older term “anesthesia dolorosa” to describe a pain that is inferred to have a central mechanism induced by a severe peripheral nerve injury.

18. Which analgesic agents are most effective in treating phantom pain?

There have been very few analgesic clinical trials in patients with phantom pain, and trials of adjuvant analgesic drugs are generally offered in a manner identical to that in other types of neuropathic pain (see Chapter 37, Adjuvant Analgesics). A placebo-controlled trial suggested that calcitonin (200 IU via brief intravenous infusion) may be effective, at least in patients with relatively short-lived phantom pain, and a trial of this drug by intranasal or subcutaneous administration should be considered early. The long-term use of opioids can sometimes be effective in treating phantom pain.

21. True or false: Psychological approaches are unlikely to be successful in the treatment of phantom pain

22. Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is another common deafferentation pain syndrome. What is the definition of PHN?

27. Can postherpetic neuralgia be prevented?

With the advent of the varicella vaccine, primary prevention of PHN is now feasible. A reduction in the incidence of this lesion presumably will be observed many years after its use becomes widespread. A recent large trial also has determined that repeat vaccination during late adulthood reduces the incidence of PHN. This treatment may soon become widespread. Studies of antiviral treatment, such as famcyclovir and valacyclovir, have shown that early treatment shortens the time of pain associated with the acute attack, in essence reducing the incidence of PHN (see Question 29).

30. Both topical and systemic analgesic drugs are commonly used in the treatment of PHN. What are the topical therapies for this condition?

31. What systemic analgesic therapies have been used for PHN?

Systemic drug therapy for PHN follows the same general approach recommended for other types of neuropathic pain (see Chapter 37, Adjuvant Analgesics). Although the usual first-line approach comprises one or more adjuvant analgesics, consider a trial of an opioid if the pain is severe. Controlled trials have recently been completed and have demonstrated the potential efficacy of opioid therapy in this disorder.