Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Becker Muscular Dystrophy

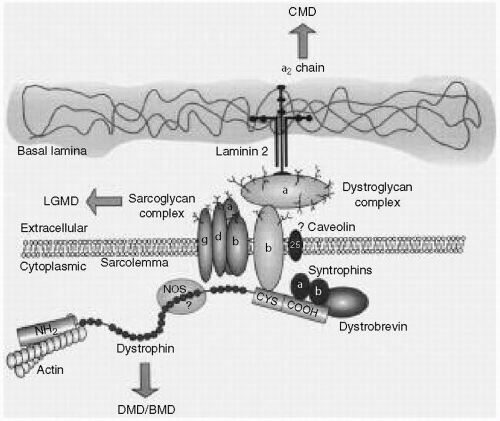

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) are the prototype muscular dystrophies affecting 1 in 3500 and 1 in 30,000 liveborn male infants, respectively. They are also known as the Xp21 dystrophies because of the locus of the involved gene. The defective gene product is dystrophin (see

Fig. 36.1). In DMD, dystrophin is essentially absent and its absence is associated with a severe phenotype; in BMD, the gene deletion or point mutation results in a reduction in the amount of dystrophin, or in the formation of a truncated protein, and a milder phenotype. Because the inheritance is X-linked-recessive, males are affected and

females are carriers. Female carriers may in fact manifest the disease to varying degrees because of skewed inactivation of the X chromosome (Lyon hypothesis).

Children with DMD typically present after the age of 2 years with a history of excessive falling, apparent clumsiness, and toe walking. Evidence of proximal weakness may be elicited while taking the history (difficulty in negotiating stairs or getting up from the floor, Gower maneuver). Examination reveals calf hypertrophy (pseudohypertrophy), proximal muscle weakness, hyporeflexia, and the presence of a Gower sign. The creatine kinase level is typically markedly elevated (in the thousands). Electromyography (EMG) is usually unnecessary for the diagnosis and shows a myopathic pattern. Muscle biopsy shows dystrophic changes (see preceding text), and special immunohistochemical stains show an absence of dystrophin. DNA studies reveal a large deletion or duplication in approximately 60% of cases. Full gene sequencing, however, will pick up smaller deletions and/or point mutations in the remainder. Children are nonambulatory by age 13, and premature death typically occurs in the early twenties.

Although no cure is available, treatment is aimed at prolonging independent ambulation (orthoses or steroids), avoiding contractures, and providing early surgical stabilization of scoliosis to preserve respiratory function and facilitate seating in a wheelchair. Cardiac and respiratory failures develop during the teenage years. Nocturnal hypoventilation resulting in early morning headache, nausea, and lethargy secondary to hypercarbia can be effectively managed with nasal bilevel positive airway pressure (Bi-PAP) ventilation. Children with DMD often have an intelligence quotient that is lower than normal and may require special educational services.

In BMD, the preservation of a reduced or altered form of dystrophin is associated with a milder phenotype. Children typically present at a slightly later age and are usually independently ambulant beyond their 16th birthday. The motor problems and the clinical, biochemical, and pathologic features are essentially the same as in DMD. Staining of the

muscle for dystrophin, however, shows some preservation of the protein, and gene deletion studies, when results are positive, may be able to predict the phenotype. If the mutation is associated with preservation of the

reading frame sequence, BMD is typically predicted (with a few exceptions), whereas if the mutation involves the promoter region or disrupts the translational reading frame

(out of frame), a Duchenne phenotype is typical. In BMD, prolonged ambulation with orthoses may be possible, and life expectancy is longer. However, cardiomyopathy often develops earlier, and must be closely monitored.

Female siblings and mothers of affected children should be screened by determining the creatine kinase level to look for possible carrier status. However, if a deletion is found in the index case, this is a more sensitive and specific marker for screening family members. Approximately two thirds of mothers of children with DMD or BMD carry the deletion. The reasons why not all mothers carry the deletion or point mutation are the high frequency of spontaneous mutation of the gene (1 in 10,000 gametes) because of its large size (2.5 million base pairs, or approximately 1% of the X chromosome) and germline mosaicism. The presence of a deletion allows for prenatal diagnosis.