Immediate Management of Life-Threatening Problems

Stroke is a cerebrovascular disorder resulting from impairment of cerebral blood supply by occlusion (eg, by thrombi or emboli) or hemorrhage. It is characterized by the abrupt onset of focal neurologic deficits. The clinical manifestation depends on the area of the brain served by the involved blood vessel. Stroke is the most common serious neurologic disorder in adults and occurs most frequently after age 60 years. The mortality rate is 40% within the first month, and 50% of patients who survive will require long-term special care.

Ischemic strokes, comprising thrombotic, embolic, and lacunar occlusions, account for over 80% of all strokes and result in cerebral ischemia or infarction. A variety of disorders of blood, blood vessels, and heart can cause occlusive strokes, but the most common by far are atherosclerotic disease (especially of the carotid and vertebrobasilar arteries) and cardiac abnormalities.

- Secondary to thrombosis or embolism

- Consider in acute neurologic deficit (focal or global) or altered level of consciousness

- No historical feature distinguishes ischemic from intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke, although headache, nausea and vomiting, and altered level of consciousness are more common in intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke

- Abrupt onset of hemiparesis, monoparesis, or quadriparesis; dysarthria, ataxia, vertigo; monocular or binocular visual loss, visual field deficits, diplopia

Assess adequacy of airway and ventilation in all stroke patients, especially in the presence of depressed level of consciousness, absent gag reflex, respiratory difficulty, or difficulty managing secretions.

Patients with inadequate ventilation (respiratory acidosis) or difficulty managing secretions will require intubation.

Stroke patients may sustain head injury due to incoordination or weakness. Conversely, patients with focal neurologic findings due to head trauma may be mistakenly diagnosed as suffering from stroke. If head injury is suspected from the history or clinical findings, immobilize the cervical spine. Refer to Chapter 22 for management.

Deterioration of neurologic status or the presence of brain-stem involvement (depressed sensorium, pupillary or extraocular movement abnormality, decorticate or decerebrate posturing) suggests significant cerebral edema and impending herniation. Mannitol 20% 0.5–1.5 g/kg hourly or 23.4% hypertonic saline solution 0.5–2.0 ml/kg, maintaining the head of the bed at greater than a 30° angle are medical therapies for elevated intracranial pressure associated with cerebral edema from ischemic stroke. However, medical therapy for cerebral edema associated with ischemic stroke does not appear to alter the patient’s outcome.

(See Chapter 19 for management of seizures.) Consider prophylaxis for seizure. Give intravenous phenytoin, 15–18 mg/kg at a rate not greater than 50 mg/min, or fosphenytoin, 15–20 mg/kg PE (phenytoin equivalents) intravenously.

Occasionally patients with hypoglycemia may have focal neurologic deficits that may mimic a stroke. Confirm the presence of hypoglycemia using a glucometer or reagent strips before giving 50 mL of 50% dextrose solution. Stroke patients with elevated serum glucose may have a worsened outcome.

Emergency CT scan of the head should be obtained early. This is the most readily available method for reliably detecting the presence of hemorrhage and focal cerebral edema. MRI, especially diffusion weighted, has enhanced the diagnosis of ischemic stroke.

Accurate diagnosis and identification of the underlying cause of the stroke are important for appropriate evaluation and treatment. Conditions that predispose to strokes should be sought and corrected. A systematic approach to the evaluation of the patient with stroke is detailed below and can be modified depending on the urgency of the patient’s condition.

The goal is to determine the exact time of onset of symptoms since the current recommended window of opportunity for thrombolytic therapy is 3 hours. Patients who awake with symptoms are considered to have symptom onset at the time they were last “normal” neurologically; when they went to sleep.

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TIAs, hyperlipidemia, smoking, family history, and use of oral contraceptives predispose to atherosclerotic disease. Cardiac disorders such as changing cardiac rhythms (especially atrial fibrillation), dyskinetic myocardium, and valvular heart disease are associated with increased risk for embolic strokes (Table 37–1). Bleeding dyscrasias, hypercoagulable states, blood disorders (especially sickle cell disease), and vascular disorders are also associated with a risk for stroke. Carotid artery bruits in patients with TIAs or stroke suggest the possibility of emboli derived from atheromatous plaques.

|

A thorough examination may reveal the underlying cause for the stroke and direct treatment.

Vital signs—Record the body temperature. Hypertension is a risk factor for stroke, and markedly elevated blood pressure may require treatment.

Head—Arteriovenous malformations may be detected by auscultation of the head for bruits. Palpate the temporal arteries for tenderness, nodularity, or absence of pulse suggestive of giant cell arthritis. Search for any evidence of trauma.

Eyes—Examination of the retina may reveal visible emboli in the retinal vessels.

Neck—The carotid arteries should be examined (one at a time) for presence of bruits and reduction of pulsation. Although these findings are not specific for carotid disease, further carotid studies may be warranted to evaluate for possible carotid endarterectomy.

Heart—Changing cardiac rhythms and murmurs or valvular disease are associated with increased risk of embolization from the heart.

Skin—Ecchymosis and petechiae may suggest blood disorders or vasculitis as causative factors. Presence of recent needle tracks or subungual splinter hemorrhages suggests the possibility of septic emboli derived from infected heart values.

Lung sounds—Auscultate for possible aspiration pneumonia or pulmonary edema.

A rapid neurologic examination should be performed in the emergency department and should focus on (1) localizing the anatomic site of deficit as an aid in determining the specific stroke syndrome and (2) assessing the degree of neurologic impairment, from which improvement or worsening can be assessed.

Level of alertness—Reduced mental alertness can be a sign of extensive injury from hemorrhage, brain-stem infarction or herniation, or metabolic changes.

Cognitive—Assess response to commands and fluency of speech. Aphasia and apraxia are associated with involvement of the cerebral cortex and anterior (carotid) circulation; lacunar infarction or disturbance of posterior (vertebrobasilar) circulation is unlikely.

Cranial nerves—Visual field abnormalities exclude lacunar infarction. Abnormal pupillary reflexes and ocular palsies are brain-stem findings and are associated with disturbance of posterior circulation or impending brain herniation.

Motor—Hemiparesis can be associated with disturbance of the anterior or posterior circulation. Generally, in anterior circulation strokes, the face, hand, and arm are affected more than the leg. In lacunar infarction and posterior circulation strokes, this pattern is less common. Hemiparesis involving one side of the face and the other side of the body is due to disturbance of posterior circulation.

Sensory—Hemisensory deficits without associated motor involvement are usually due to lacunar infarcts. Astereognosis (inability to identify objects by touch) and agraphesthesia (inability to recognize figures traced on the skin) are cortical sensory deficits and are due to disturbance of anterior circulation.

Cerebellar—Hemiataxia suggests involvement of the cerebellum or the brain stem, or lacunar infarction deep in white matter.

The NIH stroke scale (Table 37–2) is a 13-item scoring system integrating neurologic examination components, language, and levels of consciousness that indicate the severity of neurologic dysfunction. The maximum score is 42, signifying devastating stroke, and 0 is normal. Score of 1–4 is considered minor stroke, 5–15 moderate stroke, 15–20 moderately severe stroke, and >20 a severe stroke.

| 1a. Level of consciousness | 0 = Alert |

| 1 = Drowsy | |

| 2 = Stuporous | |

| 3 = Comatose | |

| 1b. LOC questions: Ask the month and the patient’s age | 0 = Answers both questions correctly |

| 1 = Answers one question correctly | |

| 2 = Answers neither question correctly | |

| 1c. LOC commands: Close your eyes and make a fist | 0 = Performs both tasks correctly |

| 1 = Performs one task correctly | |

| 2 = Performs neither task correctly | |

| 2. Best gaze | 0 = Normal |

| 1 = Partial gaze palsy | |

| 2 = Forced deviation | |

| 3. Visual fields | 0 = No visual loss |

| 1 = Partial hemianopia | |

| 2 = Complete hemianopia | |

| 3 = Bilateral hemianopia | |

| 4. Facial paresis | 0 = Normal symmetrical movements |

| 1 = Minor paralysis | |

| 2 = Partial paralysis | |

| 3 = Complete paralysis | |

| 5–8. Best motor (repeat for each arm and leg) | 0 = No drift |

| 1 = Drift | |

| 2 = Some effort against gravity | |

| 3 = No effort against gravity | |

| 4 = No movement | |

| 9. Limb ataxia | 0 = Absent |

| 1 = Present in one limb | |

| 2 = Present in two limbs | |

| 10. Sensory (pinprick) | 0 = Normal |

| 1 = Partial loss | |

| 2 = Dense loss | |

| 11. Best language | 0 = No aphasia |

| 1 = Mild-to-moderate aphasia | |

| 2 = Severe aphasia | |

| 3 = Mute | |

| 12. Dysarthria | 0 = Normal |

| 1 = Mild-to-moderate dysarthria | |

| 2 = Severe dysarthria | |

| 13. Neglect/inattention | 0 = No abnormality |

| 1 = Partial neglect | |

| 2 = Complete neglect | |

| Total score | 0–42 |

The neurologic deficits may evolve over minutes to hours and are typical for a specific vascular distribution. Motor and sensory pathways are impaired. Headache and vomiting are rare. The diagnosis is made on the basis of the clinical findings and exclusion of hemorrhage by CT scan. MRI and repeat CT scan at 48–72 hours will often confirm the diagnosis when the initial study is normal.

The following blood tests should be obtained in most patients with focal neurologic deficits:

- Complete blood count and platelet count (to detect blood dyscrasias), and prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time for coagulation disorders.

- Glucose level, because both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia may cause focal neurologic findings that can mimic stroke.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate to detect vasculitis or arteritis.

- Toxicologic screen if drug use is suspected.

An electrocardiogram may reveal new arrhythmias or conversion to a normal rhythm, both of which are associated with increased risk for emboli. Presence of myocardial infarction or persistent changes suggestive of a ventricular aneurysm also increases the risk for stroke.

These studies are essential for localizing the lesion; distinguishing hemorrhagic from ischemic stroke; and identifying other intracranial disease, such as tumor or abscess, which can be confused with strokes. A noncontrast CT scan should be obtained in any suspected stroke patient.

Thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke may be considered. The American Heart Association in conjunction with American Stroke Association and others have published guidelines for its use. Management of acute ischemic stroke is handled on a case-by-case basis. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) can be used if the following criteria are met.

- Ischemic stroke in patient with a measurable deficit, the deficit must not be resolving spontaneously and the nuerological signs should not be minor and isolated.

- Caution should be used with major deficits (NIHSS >22).

- Patient has symptoms consistent with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- The time of onset of the stroke is clearly defined, and treatment is started within 3 hours after the onset of symptoms.

- A noncontrast CT without evidence of (1)hemorrhage and (2) a multilobar infarction (hypodensity of >1/3 of cerebral hemisphere).

- No history of head trauma or previous stroke in the previous 3 months.

- No myocardial infarction in the previous 3 months.

- No gastrointestinal or urinary tract hemorrhage in the previous 21 days.

- No major surgery in the previous 14 days.

- No arterial punctures in a noncompressible site in the previous 7 days.

- No previous history of intracranial hemorrhage.

- Systolic blood pressure is less than 185 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure is less than 110 mm Hg.

- No evidence on examination of trauma or active bleeding.

- Patient is not taking oral anticoagulants or an INR of ≤1.7 if taking or anticoagulants.

- Platelet count >100,000/mm3.

- If the patient has received heparin within the previous 48 hours the PTT must be in the normal range.

- Blood glucose must be ≥50 mg/dL.

- Seizure with post ictal residual neurologic deficits (Todds Paralysis) or seizure with onset of stroke.

- Full discussion with the patient and or family members to understand the potential risks and benefits of t-PA treatment.

Dosage and Administration of t-PA:

- Give 0.9 mg/kg body weight of intravenous t-PA up to a maximum of 90 mg.

- Give 10% of the dose as a bolus and then administer the rest of the dose as a continuous infusion over 1 hour.

- Do not give anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs for 24 hours after treatment.

Acute stroke patients that receive t-PA should be admitted to an intensive care setting.

Patients with a major stroke due to occlusions of the middle cerebral artery that present within 6 hours or less and are not candidates for intravenous t-PA may be considered for intra-arterial thrombolysis. This procedure should only be done in an experienced stroke center by qualified interventionalists with immediate access to angiography.

All patients with an acute ischemic stroke should be hospitalized in a location based on their clinical condition. Patients that receive t-PA should be admitted to an intensive care unit.

- Sudden onset of severe headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Photophobia, visual changes

- Loss of consciousness

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) occurs secondary to bleeding in the subarachnoid space. It is a medical emergency. Approximately 80% are due to saccular or berry aneurysms. The rest may be due to trauma or arteriovenous malformation. Risk factors include family history of SAH, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, connective tissue diseases, hypertension, smoking, and heavy alcohol use.

Patients usually complain of “the worst headache of my life” or “thunderclap” headache. Commonly associated symptoms include nausea and vomiting, neck stiffness, and photophobia. Patients who present with stupor or coma are at high risk for mortality.

A high index of suspicion must be raised in patients presenting with early warning signs of a sentinel leak. They are frequently misdiagnosed and early diagnosis can be lifesaving. Grading of subarachnoid bleeds is based on the patient’s condition on presentation. The World Federation of Neurological Surgeons grading scale is as follows:

| Grade | Glasgow Coma Score |

|---|---|

| I | 15 |

| II | 14 or 13 without motor deficit |

| III | 14 or 13 with motor deficit |

| IV | 12–7 with or without deficit |

| V | 6–3 12–7 with or without deficit |

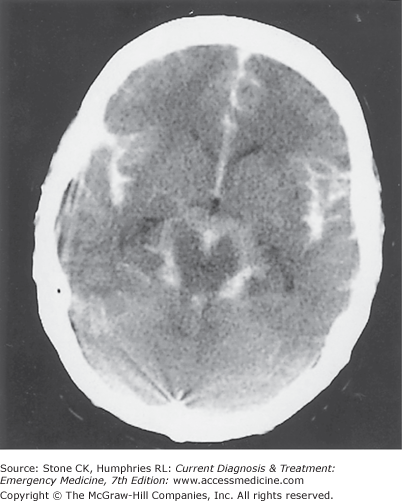

A CT scan should be performed as the first diagnostic study (Figure 37–1). CT scan is up to 98% accurate within the first 12 hours. Lumbar puncture should be performed if the CT scan does not demonstrate blood but the suspicion for SAH remains high. Spinal fluid demonstrating xanthochromia is diagnostic. However, it takes 12 hours after the bleeding for the spinal fluid to become xanthochromic and it will remain xanthochromic for approximately 2 weeks. Blood in the CSF may be due to SAH or a traumatic lumbar puncture. The reliability of decreasing erythrocyte count to identify a traumatic lumbar puncture is questionable. If the diagnosis is still in doubt angiography may be indicated.

Angiography is the gold standard for detecting aneurysms but the newer imaging modalities of MR angiography (MRA) and CT angiography (CTA) are improving. CTA is easier to perform in critically ill patients compared to MRA. CTA has a sensitivity between 77 and 100%.

Aneurysmal rebleeding may be secondary to uncontrolled hypertension or aneurysmal clot fibrinolysis. Surgical clipping or endovascular coiling is strongly recommended to reduce the rate of rebleeding.

Because seizures increase the risk of rebleeding after an SAH, prophylactic use of an anticonvulsant, for example, intravenous fosphenytoin or phenytoin, 15–20 mg/kg, is recommended.

Hypovolemia and hyponatremia can occur secondary to the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Treatment involves intravenous hydration with isotonic crystalloid. A central intravenous monitor is desirable.

Acute obstructive hydrocephalus—This form of hydrocephalus occurs in about 20% of patients after SAH. Ventriculostomy is recommended, although it may increase the risk of rebleeding or infection.

Chronic communicating hydrocephalus—This form of hydrocephalus is a frequent occurrence after SAH. A temporary or permanent cerebrospinal fluid diversion is recommended in symptomatic patients.

Vasospasm, or delayed cerebral ischemia, remains a frequent complication with high morbidity and mortality rates. Nimodipine, 60 mg orally every 4 hours, is strongly recommended.

The acute management of elevated blood pressure in SAH is controversial. There is no evidence that lowering blood pressure decreases rebleeding or the rate of cerebral infarction. Antihypertensive therapy should be reserved for severe blood pressure elevations and should be controlled balancing the risk of hypertension related rebleeding and maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure.

Surgical clipping or endovascular coiling, depending upon the resources available, should be performed to reduce the rate of rebleeding.

- No specific signs or symptoms reliably distinguish between intracerebral hemorrhage and ischemic stroke

- Symptoms vary depending on affected area and extent of bleeding

- Patients are more likely to exhibit signs of increased intracranial pressure; seizures more common

- Headache often severe and sudden

- Nausea and vomiting, hypertension, altered sensorium

Intracerebral hemorrhage is twice as common as SAH and even more likely to result in a major disability or death. Bleeding occurs primarily in the brain parenchyma, although blood may appear in the cerebrospinal fluid. Symptoms are due to mass effect of the hematoma with displacement and compression of adjacent brain tissue. The most common cause is advancing age and damage of intracerebral arterioles by long-standing systemic hypertension. Other causes include anticoagulation, alcohol abuse, thrombolytic therapy, bleeding diathesis, neoplasms, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, infections, and arteriovenous malformations.

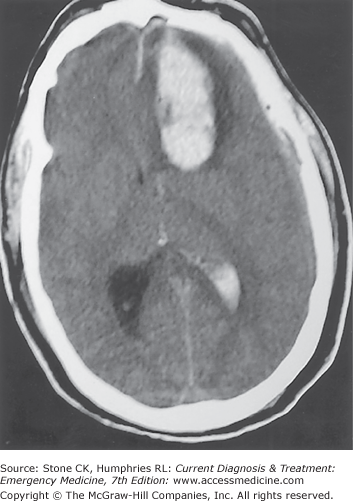

Clinical findings depend on the site of the hemorrhage but occur abruptly and progress within minutes to a few hours. Headache and vomiting are frequent symptoms. Focal neurologic deficits are prominent, since most bleeding sites about the basal ganglia, thalamus, and internal capsule. Abrupt onset of coma and prominent brainstem findings (pinpoint pupils, absent extraocular movements) are characteristic of pontine hemorrhage. A CT scan is diagnostic and is the imaging study of choice (Figure 37–2). MRI, MRA, and CTA are useful in detecting structural abnormalities such as malformations and aneurysms.

Ataxia and cerebellar abnormalities, with absent or mild hemiparesis, are characteristic of cerebellar hemorrhage. It is particularly important to diagnose hypertensive intracerebellar hemorrhage rapidly, because fatal brain-stem compression may occur rapidly. Emergency surgical decompression of intracerebellar hemorrhage can be lifesaving. Because the clinical differentiation from acute vestibular dysfunction may be difficult, patients with sudden onset of disequilibrium and vomiting require a CT scan of the brain to exclude cerebellar hemorrhage.

As with all other emergencies, initial management of a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage is directed toward airway, breathing, and circulation. A directed history and physical examination are essential to assess for underlying clues and deficits. If the patient exhibits need for airway protection, tracheal intubation should be performed.

Blood pressure management is based on a theoretical rationale: lower the blood pressure and decrease the risk of ongoing bleeding from ruptured small arterioles. The converse theory therefore holds that aggressive treatment of blood pressure may decrease cerebral perfusion pressure and worsen brain injury. If the patient’s systolic blood pressure is >200 mm Hg or MAP is >150 mm Hg, institute aggressive blood pressure reduction with continuous IV medications such as labetalol 20 mg bolus followed by 2 mg/min infusion nitroprusside 0.1–10 micrograms/kg/min or nicardipine 5–15 mg/h. If systolic blood pressure is >180 mm Hg or MAP is >130 mm Hg and there is evidence of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), along with monitoring of ICP, blood pressure should be reduced with intermittent or continuous medications to keep the cerebral prefusion pressure between 60 and 80 mm Hg. If systolic blood pressure is >180 mm Hg or MAP is >130 mm Hg and there is no clinical evidence of ICP elevation, a more modest decrease in MAP to 110 mm Hg is appropriate using intermittent or continuous medications.

Treatment of suspected elevation of ICP should be treated in the ED with simple measures such as elevation of the head of the bed, analgesia and sedation.

Neurosurgical consultation should be obtained. The decision about whether and when to operate remains controversial. Patients with a cerebellar bleed of >3 cm who are demonstrating neurologic deterioration, have brainstem compression or hyrocephalus from ventricular obstruction, should undergo surgical decompression.

All patients with an intracerebral hemorrhage should be monitored and treated in an intensive care unit.

Delirium and acute confusional states are among the most difficult problems confronting the emergency physician. The patient’s mental status can be assessed quickly using a classification scheme. Such schemes classify patients according to whether or not they are alert, their ability to attend, and their memory capability, allowing the physician to differentiate among coma, delirium, and dementia.

Confused patients are often uncooperative or combative, making evaluation difficult. Signs and symptoms may be manifestations of a life-threatening underlying condition demanding prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent irreversible brain damage (Table 37–3). Although evaluation may be difficult, every patient with an acutely altered state of consciousness must be examined and a history taken so that the cause can be established, if possible, in the emergency department. If the diagnosis cannot be established with certainty, the patient should be hospitalized.

|

Clear secretions as needed. Begin oxygen, if necessary, 5–10 L/min, by mask or nasal cannula. Restrain the patient only if necessary.

Insert a large-bore (≥18-gauge) intravenous catheter. Administer the following intravenously: (1) thiamine, 100 mg by slow bolus injection; (2) 50% dextrose in water, 50 mL over 3–5 minutes, if the patient is hypoglycemic by bedside finger stick glucose testing; and (3) naloxone 0.4–2 mg by bolus injection. Caution: Administration of glucose may worsen brain injury by increasing lactate in ischemic areas. Do not give glucose to patients during the acute phases of stroke or after cardiac arrest if serum glucose is normal.

Hypotension and shock with associated peripheral hypoperfusion may be associated with delirium or confusion. Treat shock with immediate intravenous administration of crystalloid solutions unless the patient is in cardiogenic shock, and follow with more specific measures (Chapter 11).

Hypoxemia or hypercapnia that develops abruptly may be associated with delirium. Assess ventilatory status by means of arterial blood gases, and correct hypoxemia or hypercapnia by administration of oxygen, assisted ventilation, or both, as needed.

Markedly elevated body temperatures (40.6°C [105°F]) may be associated with delirium or acute confusional states. Hypothermia is likely to produce confusion at body temperatures below 32.2°C (90°F) and unconsciousness at temperatures below 26.6°C (80°F). Treat by lowering or raising core temperature, as needed (Chapter 46).

Severe hypertension (when associated with papilledema and encephalopathy) is a medical emergency requiring rapid reduction of mean arterial pressure toward 110 mm Hg (Chapter 35). The diagnosis of hypertensive encephalopathy must be firmly established before antihypertensive therapy is started, however, because reduction of blood pressure when cerebral ischemia is present can severely exacerbate ischemic brain injury.

Obtain complete vital signs, including temperature.

Assess for shock (peripheral hypoperfusion).

Measure oxygen saturation and consider blood gas analysis if appropriate.

Does the delirium lighten after administration of intravenous glucose, thiamine, and naloxone? If so, consider the following possibilities:

- Hypoglycemia (diagnosis is confirmed by finding of low serum glucose)

- Wernicke encephalopathy (look for associated alcoholism, malnutrition, ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, and peripheral neuropathy)

- Opiate overdose (diagnosis is confirmed by positive response to naloxone and toxicology screen)

- Hypoglycemia (diagnosis is confirmed by finding of low serum glucose)

History—Obtain a brief history from the patient, family, friends, neighbors, ambulance attendants, or bystanders. Ask in particular about prior episodes of confusion or delirium, duration and other features of the present episode, drug usage, and previous illness.

Physical and neurologic examination—Perform a general physical examination, and look especially for signs of trauma, meningeal irritation, and cardiac disease. Signs of meningeal irritation (meningismus: stiff neck, positive Kernig and Brudzinski signs) are almost invariably present in meningitis or SAH except in very young or very old patients. The most helpful diagnostic maneuver is passive flexion of the patient’s neck, which elicits reflex knee flexion (usually unilateral) if meningeal irritation is present (positive Brudzinski sign). Perform lumbar puncture immediately in patients with meningismus in the absence of signs of increased intracranial pressure (papilledema, focal neurologic findings) for evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid. In patients with fever and focal neurologic findings, a brain abscess must be considered along with meningitis and encephalitis. A lumbar puncture is contraindicated until a CT scan has eliminated the possibility of a mass lesion. To avoid delay of needed treatment for possible meningitis while awaiting the results of the CT scan, obtain blood cultures and begin antibiotics immediately (Chapter 42).

Complete a basic neurologic examination, including tests of orientation and memory. Although focal signs may be found in metabolic brain disease (notably the fluctuating hemiparesis that may occur with hypoglycemia and hepatic encephalopathy), such asymmetric findings should be assumed to reflect a structural brain lesion until proved otherwise and a CT scan obtained for evaluation.

Laboratory studies—Send blood to the laboratory for CBC; serum electrolyte, glucose, calcium, and magnesium determinations; renal and liver function tests; carboxyhemoglobin level; and toxicology studies. Obtain urine for urinalysis and toxicology studies.

Electrocardiogram—Obtain an electrocardiogram in order to seek any abnormalities that might suggest a cardiac cause of the confusional state (eg, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, prolonged intervals). T-wave changes, however, are nonspecific and may be seen with acute intracranial events.

Special studies—CT scan is indicated in most patients with an acute change in mental status. Other special studies may be indicated based on the results of history and physical examination (eg, lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid in the patient with confusion and fever or signs of meningeal irritation).

Gastric decontamination—Administer an activated charcoal slurry (50–100 mg of activated charcoal admixed with water or sorbitol) and consider gastric lavage if ingestion or overdose of a toxin is a diagnostic possibility.

If there is evidence of trauma—even if the head itself appears uninjured—consider the possibility of traumatic brain damage (eg, subdural or epidural hematomas). CT scan may be indicated (Chapter 22).

Once life-threatening conditions have been ruled out, a more specific diagnosis can be attempted. Main causes are shown in Table 37–4. Delirium or confusion occurring in patients with AIDS is discussed in Chapter 42.

| Etiologic Category | Clinical Findings |

|---|---|

| Central nervous system mass lesion (subdural hematoma, cerebral infarction, brain tumor) | Somnolence; neurologic examination shows focal or asymmetric abnormality. Posterior nondominant parietal lobe strokes present with an agitated delirium, without hemiparesis. |

Meningitis or meningoencephalitis Infectious, carcinomatous, or chemical meningitis secondary to subarachnoid hemorrhage | Headache, fever, meningeal signs, cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis |

Seizure disorders Confusional states following seizures (postictal states) Psychomotor status epilepticus | History or evidence of seizures, especially seen in seizure patients with superimposed metabolic abnormality, encephalitis, or diffuse cerebral damage, in whom postictal state may be prolonged |

| Amnestic states | Findings confined to recent memory loss |

| Fluent aphasias | Sudden onset; patient alert; mild right hemiparesis (may be absent). Excessive speech with frequent word substitutions and nonsense phrases |

| Psychiatric disease (thought disorders and hysteria) | Paranoia prominent; auditory hallucinations common; disorientation as to person, which is greater than that as to place, which is greater than that as to time. Recent memory preserved |

Head trauma (acute posttraumatic delirium, post-concussion syndrome) Metabolic encephalopathy; drug intoxication or withdrawal | Recent history or evidence of head trauma Fluctuations in mental status (lucid intervals); asterixis; myoclonus; tremor; visual hallucinations; disorientation as to time, which is greater than that as to place, which is greater than that as to person; nystagmus |

Almost all patients presenting with an acute confusion will require hospitalization.

Emergency Management of Specific Central Neurologic Disorders

- Most frequent in basal ganglia and internal capsule

- Five classical lacunar syndromes

- Pure motor stroke/hemiparesis

- Most common syndrome

- Usually affects face, arm, leg equally

- Transient sensory symptoms (but not signs) may be present

- Most common syndrome

- Ataxic hemiparesis

- Second most common syndrome

- Weakness and clumsiness on one side of body; legs affected more commonly than arms

- Second most common syndrome

- Dysarthria/clumsy hand

- Facial weakness

- Severe dysarthria

- Slight weakness and clumsy hand

- Facial weakness

- Pure sensory stroke (Thalamus)

- Persistent numbness or tingling on one side of the body (face, arm, leg, trunk)

- Unpleasant sensation

- Persistent numbness or tingling on one side of the body (face, arm, leg, trunk)

- Mixed sensorimotor stroke

- Hemiparesis or hemiplegia noted

- Ipsilateral sensory impairment

- Hemiparesis or hemiplegia noted

- Pure motor stroke/hemiparesis

Lacunar stroke results from occlusion of the small penetrating arteries of the brain by lipohyalinotic deposits, which are a product of long-standing hypertension. The areas of infarction are generally small, and multiple old infarct sites may also be identified on CT scan. The clinical findings are distinct and may range from pure motor or pure sensory deficits to incoordination and clumsiness of the hand or ataxia of the arm or leg. CT scan is often normal or may show small areas of reduced attenuation in the affected areas, usually in the internal capsule, basal ganglia, or upper brain stem.

Treatment is supportive and consists mainly of blood pressure control. The prognosis is generally good. Patients should usually be hospitalized for observation.

- Nonspecific presenting signs and symptoms, neurologic deficits

- Headache, facial pain, neck swelling, pulsatile tinnitus

- More common in young adults

- May follow traumatic event or simple manipulation of the neck, or may be spontaneous

- Horner syndrome/bruit

An acute progressive syndrome of carotid or vertebral artery ischemia almost invariably associated with anterior or posterior neck pain suggests carotid or vertebral artery dissection, respectively. A history of recent neck trauma is frequent and may be relatively trivial, such as chiropractic manipulation. However, dissection may occur spontaneously. The patient will complain of pain, transient monocular visual loss. They may also present with Horner’s Syndrome. Emergent CT scan of the head is usually indicated to evaluate for ischemic complications. MR or CT angiography has displaced conventional catheter angiography as the imaging study of choice to diagnose arterial dissection.

Current opinion favors anticoagulation acutely and for several months thereafter to reduce the potential for distal embolization of platelet aggregates formed on the damaged vessel wall. Surgical or endovascular treatment is usually not primarily indicated and should be considered in patients whom medical management has failed to prevent further ischemic signs or those who have contraindications to anticoagulation.

- Rapid onset of neurologic symptoms lasting typically less than 60 minutes and rarely up to 24 hours

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree