CHAPTER 20 Needle Acupuncture

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

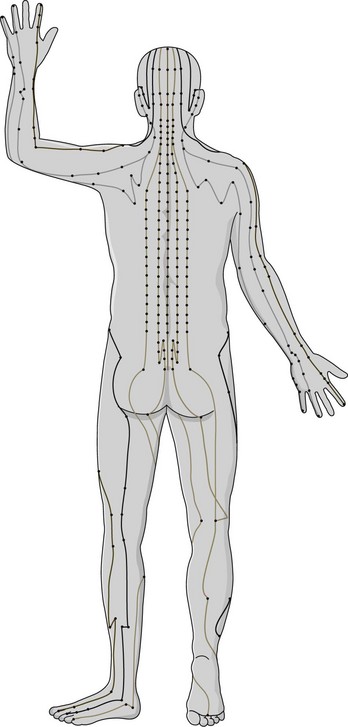

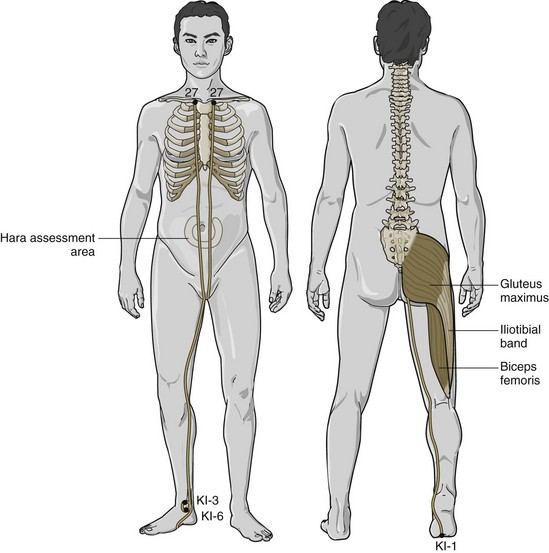

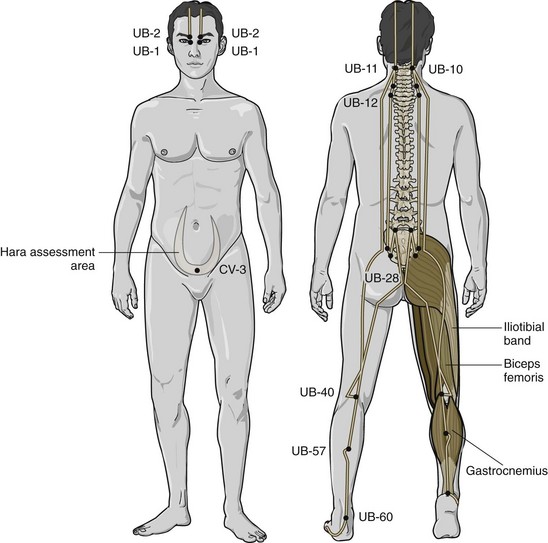

The term acupuncture encompasses a variety of different procedures and techniques that involve the stimulation of specific points along the body thought to be related to various bodily functions. Needle acupuncture involves stimulating these points by penetrating the skin with thin, solid, metallic needles that can be further stimulated manually or electrically (Figure 20-1). There are many different types of needle acupuncture used throughout the world, including Japanese Meridian Therapy, French Energetic acupuncture, Korean Constitutional acupuncture, and Lemington Five Elements acupuncture. In recent decades, new forms and styles of needle acupuncture have evolved, including ear (auricular) acupuncture, hand acupuncture, foot acupuncture, and scalp acupuncture.1 These forms of acupuncture attempt to achieve the same effects as traditional acupuncture by stimulating only points within those targeted areas. Massage acupuncture, also termed acupressure, is reviewed in Chapter 16. Acupuncture was traditionally based on the belief that health is maintained in a delicate state of balance by two opposing forces, termed yin and yang. Yin represents the cold, slow, or passive force, whereas yang represents the hot, excited, or active force. Disease or dysfunction is thought to arise when there is an imbalance of yin and yang, which leads to a blockage in the flow of vital energy (known as qi, pronounced chi) along pathways known as meridians (Figure 20-2).2

History and Frequency of Use

Acupuncture originated in China more than 2000 years ago and is one of the oldest, most commonly used traditional systems of healing in the world. Its popularity in the West has grown rapidly over the past 30 years. Acupuncture gained particular notoriety in 1971 after James Reston, a journalist with The New York Times, published an article on his personal experience with the intervention. While traveling in China, he suffered acute appendicitis and required an emergency appendectomy. His postoperative pain was managed with acupuncture by inserting thin needles into his elbows and knees to stimulate and relieve pressure in the intestine and stomach, which were thought to be important in his condition. Having experienced complete relief of symptoms with acupuncture, Reston is often credited with exposing Americans to this method of healing.3

The use of acupuncture appears to be gaining popularity in recent years as increasing numbers of people with chronic low back pain (CLBP) seek complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). A survey of CAM use among the general adult population of the United States conducted in 1991, reported that acupuncture had been used by 0.4% of respondents in the past year, 91% of whom had consulted with a health care provider.4 When this survey was repeated in 1997, the use of acupuncture in the previous 12 months had grown to 1%.4 The total number of visits to acupuncture practitioners in 1997 was estimated at five million. A prospective study of CAM use among 1342 patients with low back pain (LBP) who presented to general practitioners (GPs) in Germany reported that 13% received acupuncture in the subsequent 1 year follow-up.5 The use of acupuncture was statistically significantly higher among those whose GP offered acupuncture, with an odds ratio of 3.0 (95% confidence interval, 2.1 to 4.4). Acupuncture was the third most commonly reported CAM therapy after massage (31%) and spinal manipulation therapy (SMT, 26%).

Practitioner, Setting, and Availability

In North America, acupuncture is widely available and is typically practiced in a private practice setting by a variety of practitioners including acupuncturists and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners, as well as some physicians, chiropractors, and physical therapists with additional training. Licensing, credentialing, and regulations to practice acupuncture vary significantly depending on jurisdiction. In 2002, 42 states in the United States had established statutory licensure governing more than 14,000 acupuncture practitioners.6 In addition, an estimated 3000 physicians had formally studied and incorporated acupuncture into their practices.6

Procedure

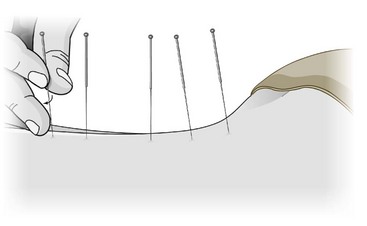

In order to determine the nature of an illness, an acupuncturist needs to conduct an assessment that may include a brief medical history, history about specific symptoms and bodily functions, traditional physical examination, and examination of the tongue, eyes, peripheral pulses, and odor. The goal of the assessment is to help determine which meridians and acupuncture points should be stimulated to address the presenting complaints (see Figure 20-2). Modern acupuncturists typically use a combination of both traditional meridian and extrameridian acupuncture points, which are fixed according to anatomic landmarks and not necessarily associated with meridians (Figures 20-3 and 20-4).

Figure 20-3 Acupuncture points and meridians in the lumbosacral region: anterior and posterior urinary bladder channels.

(Modified from Anderson S. The practice of shiatsu. St. Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Figure 20-4 Acupuncture points and meridians in the lumbosacral region: anterior and posterior urinary bladder channels.

(Modified from Anderson S. The practice of shiatsu. St. Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Once appropriate points are selected, the patient usually lies supine or prone on a treatment table while the therapist inserts acupuncture needles. Each needle is typically inserted by holding it over the desired points and gently tapping it into place until it penetrates the skin, after which it is briefly rotated and stimulated; a verbal or physical response may be sought from the patient to help confirm needle placement. A typical session with needle acupuncture may include inserting 20 to 30 needles or more. Needles are generally kept in place for 20 to 30 minutes, during which the therapist may periodically stimulate them manually by rotating the needles (Figure 20-5). Therapists may also use electrical stimulation, in which a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) device is connected to the acupuncture needles to deliver constant stimulation. Other interventions that may be used in conjunction with needle acupuncture include injection acupuncture (herbal extracts are injected into acupuncture points), heat lamps, or moxibustion (the moxa herb, Artemisia vulgaris), which is burned at the end of the needles.1 The latter interventions are not discussed in this chapter.

Theory

Mechanism of Action

In traditional needle acupuncture, there are 12 primary meridians, 8 secondary meridians, and more than 2000 associated acupuncture points on the human body; this number varies somewhat, and some texts have described and mapped only the 365 most commonly used points.7 The goal of traditional acupuncture is to select the appropriate points along different meridians that correspond to a particular illness or bodily dysfunction, and to stimulate those points with needles until balance in the body’s energy flow is restored.

In terms of Western scientific principles, it is uncertain how acupuncture functions in general and unclear how it may help CLBP in particular. It is hypothesized that acupuncture produces its effects through the central nervous system (CNS) by stimulating the production of endorphins and neurotransmitters that modulate nociception and other involuntary bodily functions.8,9 Another theory suggests that acupuncture works through the gate control theory of pain, in which the nociceptive input (e.g., CLBP) is inhibited in the CNS in the presence of another type of input (e.g., acupuncture needle).10

It is also postulated that the presence of a foreign substance (e.g., acupuncture needle) within the tissue of the body stimulates vascular and immunomodulatory factors involved as mediators of inflammation.11 Elevated levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone after acupuncture seem to support this theory.12 More recently, it was found that active myofascial trigger points at the upper trapezius muscle (corresponding to the GB 21 acupuncture point) had a lower pressure pain threshold (indicating more susceptibility to pain from that region) when compared with controls who had no pain or only latent trigger points.13 It was also reported that levels of substance P, calcitonin gene–related peptide, bradykinin, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, serotonin, and norepinephrine were elevated in the vicinity of the active myofascial trigger point.13 It is presumed that stimulating this acupuncture point could impact some of these phenomena, but further research is needed to understand the specific effects of acupuncture on CLBP.

Indication

Acupuncture is typically used for patients with nonspecific mechanical CLBP, with or without radiculopathy.14 It is uncertain which patient characteristics are associated with improved outcomes when using acupuncture for CLBP. Thomas and colleagues attempted to assess the role of prior expectations in influencing outcomes among patients receiving acupuncture for CLBP. They found that prior expectations of a negative or neutral benefit were associated with better pain outcomes at 24 months among those receiving acupuncture.15 In contrast, subgroup analysis in another randomized controlled trial (RCT) reported that higher expectations that acupuncture would be beneficial were associated with improved disability scores in CLBP compared with lower expectations.16 Thomas and colleagues also found that duration of symptoms was negatively associated with better outcomes.15 However, there is currently insufficient evidence to accurately determine which patient with CLBP would benefit most from needle acupuncture.

Assessment

Before receiving needle acupuncture, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating this intervention for CLBP. The clinician should also inquire about general health to identify potential contraindications to this intervention. In order to select the specific acupuncture points to be treated, an additional assessment may be conducted by the clinician. Studies evaluating the consistency of diagnoses and selection of acupuncture points among traditional acupuncturists for CLBP have reported mixed results.16–18

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found conflicting evidence to support the efficacy of acupuncture for CLBP.19 That CPG found that acupuncture is not more effective than trigger point injections, TENS, or self-care education for CLBP. Acupuncture was less effective than massage or SMT for CLBP, but provided short-term improvements in pain, which might be improved when combined with other interventions.

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found conflicting evidence that acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture in the management of CLBP.20 There was limited evidence that acupuncture combined with other conservative management options, including usual physical therapy (PT), care from a GP, exercise, or back school, is more effective than any of those interventions alone. That CPG also found limited evidence that acupuncture is as effective as brief education or self-care for CLBP. There was moderate evidence that acupuncture is not more effective than trigger point injections or TENS for CLBP, and there was limited evidence that acupuncture is less effective than massage or SMT for CLBP. That CPG did not recommend acupuncture in the management of CLBP.

The CPG from Italy in 2007 found evidence that acupuncture is not effective in the management of CLBP.21

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found evidence to support the efficacy of acupuncture with respect to improvements in pain and function.22 There was evidence that acupuncture was more effective than usual care for CLBP, and the CPG recommended offering a course of acupuncture when other conservative management options do not obtain adequate pain relief. That CPG recommended a maximum of 10 sessions of acupuncture over a period of up to 12 weeks for CLBP.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate quality evidence to support the efficacy of acupuncture with respect to improvements in pain.23 That CPG recommended acupuncture as one management option if patients do not achieve adequate pain relief with self-care alone.

Findings from the CPGs are summarized in Table 20-1.

TABLE 20-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Acupuncture for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 19 | Belgium | May provide short-term improvements in pain |

| 20 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 21 | Italy | Evidence that acupuncture is not effective |

| 22 | United Kingdom | Recommended if other options do not obtain adequate pain relief (maximum 10 sessions over 12 weeks) |

| 23 | United States | Recommended if self-care alone does not provide pain relief |

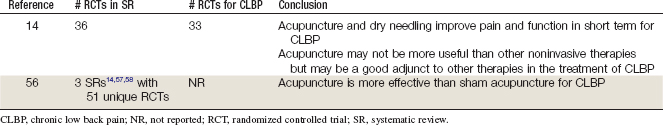

Systematic Reviews

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 2005 by the Cochrane Collaboration on acupuncture and dry needling for LBP.14 Of 35 RCTs, 3 examined acute LBP and 32 reported on CLBP.24–55 For CLBP, two RCTs found a statistically significant difference between acupuncture and no treatment for short-term pain relief and functional improvement.4,53 One of these RCTs observed significantly decreased pain but not improvement in the intermediate-term for acupuncture versus no treatment.53 Five RCTs showed that acupuncture was more effective than sham acupuncture for short-term pain relief in CLBP.44,48–50,52 One small trial failed to reach statistical significance.30

For intermediate-term pain relief, three RCTs did not find statistically significant differences between acupuncture and sham acupuncture, and one RCT found this same result for longer-term pain. None of the RCTs found statistically significant differences between acupuncture and sham acupuncture for function in the short- or intermediate-term.30,49,50 Compared with other interventions, acupuncture was less effective at decreasing pain and improving function than SMT and massage in the long-term and was equally effective as self-education.40,46 Acupuncture was more effective than TENS at decreasing pain in the short-term, yet another RCT observed no differences.30,43 Acupuncture and TENS were equally effective at improving function in these two RCTs.30,43

Four RCTs assessed the effects of adding acupuncture to other therapies, such as exercise, medication, heat therapy, back education, and behavioral therapy. These trials found that adding acupuncture to these interventions improved pain and function in the short- and intermediate-terms versus the interventions alone. This SR concluded that acupuncture and dry needling improve pain and function in the short-term for CLBP. This review also concluded that acupuncture may not be more effective than other available non-invasive interventions but might be useful to add to other therapies to boost their effectiveness. However, there was insufficient evidence supporting acupuncture and dry needling for acute LBP.14

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR of other published SRs was conducted in 2006 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic LBP.56 That review identified three SRs related to acupuncture for LBP, including the Cochrane Collaboration review mentioned earlier.14,57,58 Two of these SRs were high quality and concluded that there is insufficient evidence supporting the use of acupuncture for acute LBP but that acupuncture improves pain in the short-term for CLBP.14,57 These SRs included a total of 51 unique RCTs (references were not provided). Three new trials were also identified (duration of LBP not reported); one did not find any statistically significant differences between acupuncture and sham acupuncture for pain or function, one did not find any clinically meaningful differences between acupuncture and no acupuncture for pain or function, and one found statistically significant differences for pain and medication use for acupuncture versus usual care.59–61 This SR repeated the results of the Cochrane review mentioned previously and concluded that acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture for CLBP.14,56 There was insufficient evidence to support acupuncture for acute LBP.

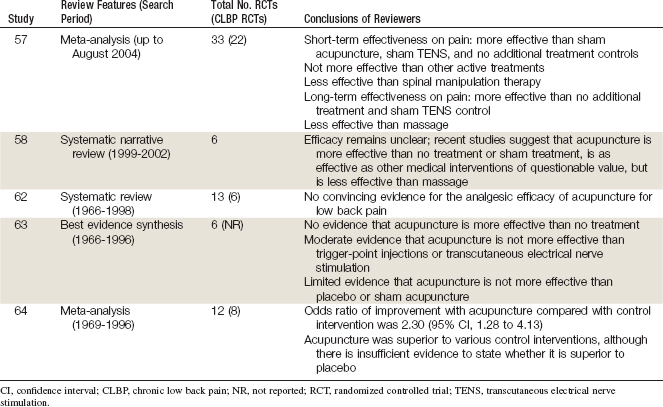

Findings from these SRs are summarized in Table 20-2.

Other

Several other SRs and meta-analyses have been published evaluating the effectiveness of acupuncture for CLBP.57,58,62–64 Their findings are summarized in Table 20-3. The more recent reviews suggest that acupuncture is equally effective as other active conservative therapies and may be a useful adjunct to some of them.57 The earlier reviews have similar conclusions to that found in the CPGs on CLBP.58,62–64

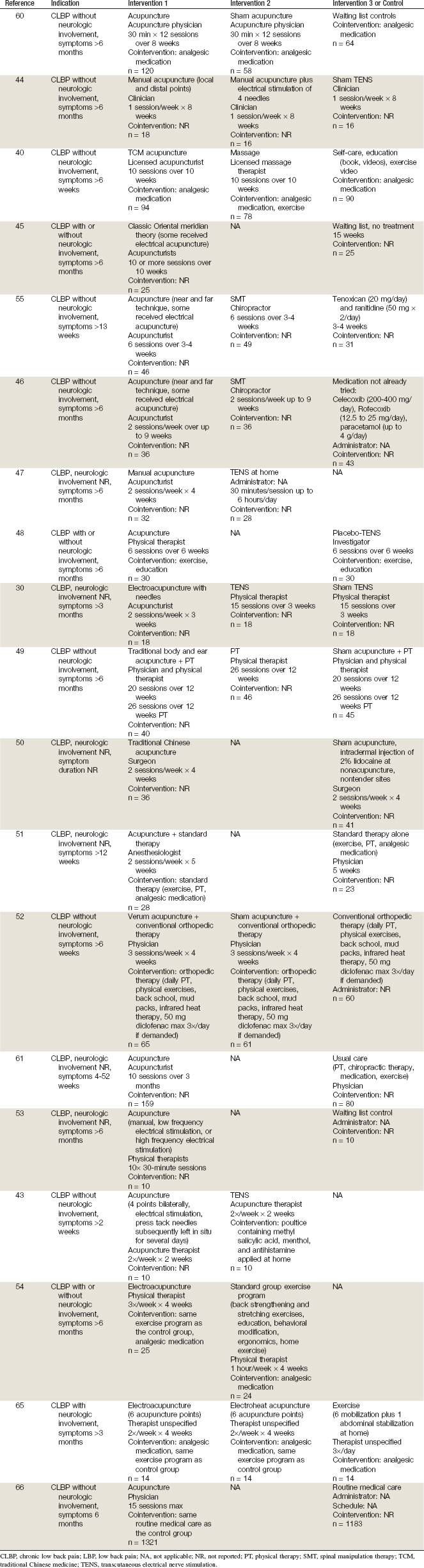

Randomized Controlled Trials

Nineteen RCTs involving needle acupuncture for CLBP, published in English after 1980 were identified.30,40,43–55,60,61,65,66 Their methods are summarized in Table 20-4, and their results are briefly described here.

Brinkhaus and colleagues60 performed an RCT including patients with CLBP. To be included, participants had to experience symptoms lasting longer than 6 months. Participants were randomized to one of three groups: (1) acupuncture, (2) sham acupuncture, or (3) waiting list control. Acupuncture was delivered by an acupuncture physician to both the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups for twelve 30-minute sessions over 12 weeks. After 8 weeks of follow-up, participants in the acupuncture group experienced a statistically significant improvement in pain compared with those in the sham acupuncture group. However, after 26 and 52 weeks of follow-up, no differences were observed between the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree