NECK STIFFNESS

LEAH TZIMENATOS, MD, CHERYL VANCE, MD, AND NATHAN KUPPERMANN, MD, MPH

Neck stiffness is an important chief complaint in children evaluated in the emergency department. Commonly, neck stiffness is accompanied by neck pain. Certain clinical conditions, however, may lead a child to hold the neck in an abnormal posture (malposition) without neck pain. The underlying causes of neck stiffness or malposition in children range from relatively benign (e.g., muscle strain, cervical adenitis) to life-threatening (e.g., meningitis, fracture, or subluxation of the cervical spine).

Torticollis (meaning “twisted neck” from the Latin roots tortus and collum) is a subset of neck stiffness. With torticollis, the child holds the head tilted to one side and the chin rotated in the opposite direction, reflecting unilateral neck muscle contraction. This may result from various pathologic processes and may or may not be associated with neck pain. Torticollis is often congenital and/or muscular in origin. It can also be associated with acquired processes such as trauma, infectious or inflammatory illnesses, central nervous system neoplasms, drug reactions, and a variety of different syndromes.

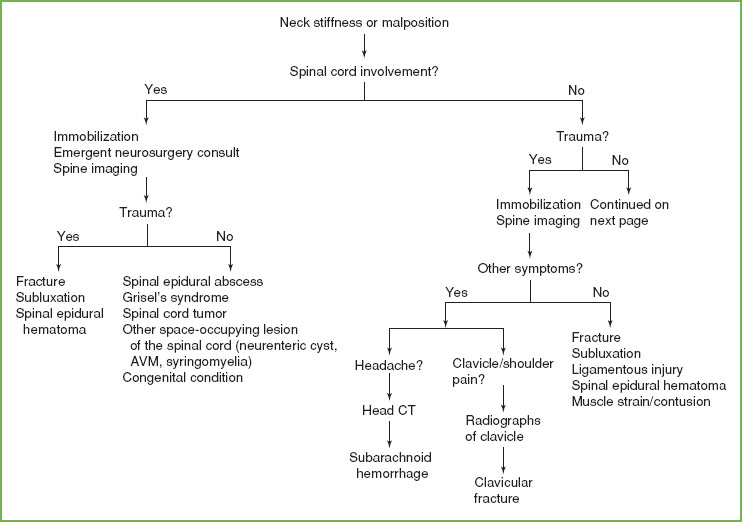

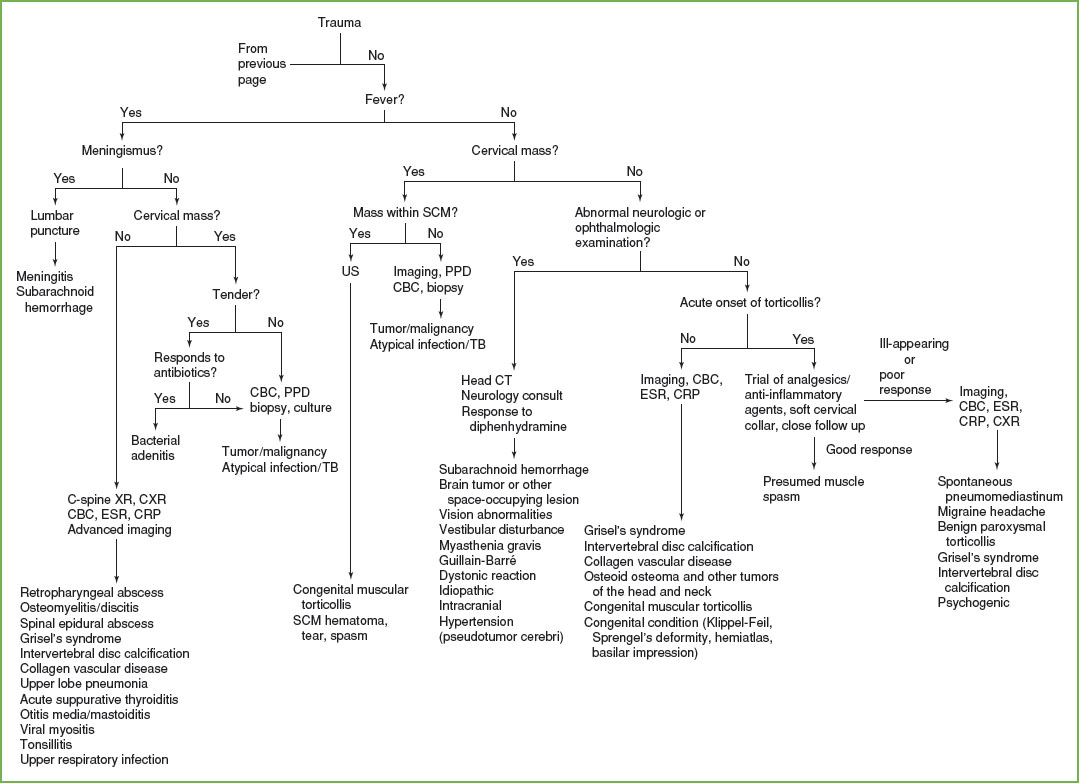

This chapter reviews the differential diagnosis of neck stiffness including torticollis, both with and without neck pain, in children. Figure 44.1 offers an algorithmic approach to help distinguish potentially life-threatening from benign causes of neck stiffness, while providing a broad differential diagnosis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Most patients presenting with neck stiffness are well appearing with benign, frequently self-limited conditions; however, the differential diagnosis of neck stiffness is broad and includes many potentially life-threatening causes, which must be considered and excluded when appropriate. A history of trauma, signs or symptoms of an infectious or inflammatory process, or evidence of spinal cord involvement may be helpful in identifying a number of specific diagnoses.

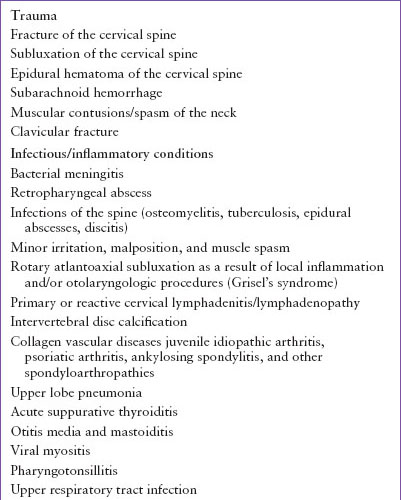

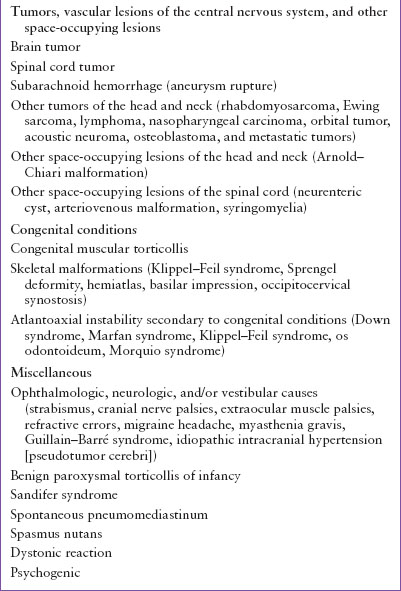

Table 44.1 lists most causes of neck stiffness in children, Table 44.2 lists the common causes, and Table 44.3 lists the life-threatening causes. The following descriptions categorize the causes of neck stiffness in children by underlying mechanism and severity.

Neck Stiffness Associated with Trauma

Potentially Life-threatening Causes

Neck trauma is a common cause of neck pain and stiffness (see Chapter 120 Neck Trauma). Fortunately, serious injuries to the cervical spine (fractures, subluxations, and spinal cord injuries) are uncommon, especially in children younger than 8 years. Because of a higher fulcrum of the cervical spine and relative weakness of the neck muscles compared to adults, these injuries generally occur in the upper cervical spine in younger children, as opposed to more widely across the cervical spine in older children and adolescents. Neck injuries in children most commonly result from high kinetic energy mechanisms, such as motor vehicle–related collisions, sports injuries, and falls.

Fractures of the Cervical Spine. Fractures of the cervical spine in children are very uncommon, occurring in 1% to 3% of hospitalized pediatric trauma patients. Although some children with fractures of the cervical spine are unresponsive at the time of evaluation, most are alert and verbal, limit their neck movement secondary to pain, and have no demonstrable neurologic deficits. At the minimum, the cervical spine should be immobilized and imaging of the cervical spine should be obtained on any child with an altered level of consciousness, pain or stiffness of the neck, any neurologic deficits, or distracting painful injuries after blunt trauma. Imaging should also be obtained in those who are unable to perceive pain (as a result of alcohol or drugs) or describe their symptoms. A large prospective study, the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS), of blunt trauma victims identified five criteria (posterior midline cervical tenderness, altered alertness, distracting injury, intoxication, and focal neurologic signs) that identified all children with cervical spine injuries; however, there were few children younger than 9 years and none younger than 2 years with cervical spine injuries in that study. A multicenter attempt to retrospectively validate the NEXUS criteria among a different cohort of children (including those younger than 2 years) demonstrated a lower sensitivity, suggesting the need for refinement of these criteria before routine use in children. A more recent case-control study of 540 children with cervical spine injuries identified eight important risk factors: altered mental status, focal neurologic findings, neck pain, torticollis, substantial torso injury, conditions predisposing to cervical spine injury, diving, and high-risk motor vehicle collision mechanisms. Prospective refinement of risk factors, particularly in younger children, is necessary.

Subluxation of the Cervical Spine. Traumatic subluxations of the cervical spine are more common than fractures and are more likely to present more than 24 hours after injury. Subluxation may result from minor trauma (e.g., falls from low heights) but typically occurs after more severe trauma (see Chapter 120 Neck Trauma). The most common subluxation is rotary (or “rotatory”) atlantoaxial subluxation. Clinically, rotary subluxation typically causes neck pain and torticollis without focal neurologic symptoms because the transverse ligament of the atlas remains intact and the spinal cord is not compromised. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) spasm and neck tenderness are localized to the same side as the head rotation as the SCM attempts to “reduce” the deformity. This is in contrast to muscular torticollis, in which the spastic, tender SCM muscle is opposite to the direction of head rotation. In addition, in rotary subluxation, there is palpable deviation of the spinous process of C2 in the same direction as the head rotation. In contrast, during normal neck rotation beyond 20 degrees, the spinous process of C2 deviates to the contralateral side.

FIGURE 44.1 Approach to the child with stiff or malpositioned neck. Diagnostic studies included in this approach are intended to be considerations that may assist with making a diagnosis depending on the specific clinical scenario. C-spine XR, cervical spine radiograph; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; CT, computed tomography; CBC, complete blood count; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; PPD, purified protein derivative; TB, tuberculosis; SCM, sternocleidomastoid; CXR, chest radiograph; US, ultrasound.

Rotary atlantoaxial subluxation may be seen on plain radiographs. An anteroposterior open-mouth radiograph typically shows the rotation of C1 on C2, with the odontoid in an eccentric position relative to C1. However, definitive diagnosis is made by dynamic computed tomography (CT) scans of the neck showing a fixed rotation between C1 and C2 that fails to resolve with attempts to correct the torticollis. Most patients can be treated with a cervical collar and anti-inflammatory medications. Traction and immobilization may be necessary for more severe and/or long-standing rotary subluxation or if reduction is not achieved by conservative measures. Surgical intervention is rarely required.

Atlantoaxial subluxation with compromise of the spinal canal results when there is ligamentous laxity or rupture with resultant anterior movement of the atlas on the axis. Children with underlying conditions such as Down syndrome and Marfan syndrome are more susceptible to this due to laxity of the transverse ligament of the atlas. Radiographic findings may include a widened predental space and prevertebral soft tissue swelling. Treatment involves immobilization and cervical traction.

Epidural Hematomas of the Cervical Spine. Epidural hematomas of the cervical spine are uncommon but may occur even after apparently minor trauma. These may compress the spinal cord, leading to progressive neurologic symptoms and signs as well as neck stiffness or pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinal cord clearly demonstrates this injury. Emergent neurosurgical consultation and surgical decompression are indicated.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhage after trauma may lead to neck stiffness but is often accompanied by headache and/or other physical findings of head trauma. Rarely, subarachnoid hemorrhage may be due to nontraumatic causes such as aneurysm rupture.

Generally Non–life-threatening Causes

Traumatic Muscular Contusions of the Neck. Blunt trauma to the neck may result in neck pain as a result of muscular contusion and/or spasm. This is a diagnosis of exclusion and should not be entertained until a detailed physical examination and imaging of the cervical spine excludes more serious injuries. Treatment includes a soft cervical collar and analgesic medication.

Clavicular Fracture. Fracture of the clavicle in children is common and may cause torticollis because of SCM muscle spasm. This diagnosis is usually clear because pain, tenderness, and swelling are noted over the fracture site. The acute symptoms associated with clavicular fractures may occasionally mask an associated rotary atlantoaxial subluxation.

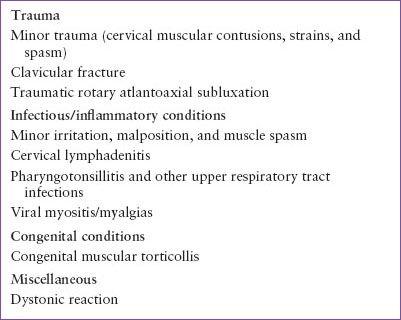

TABLE 44.1

CAUSES OF NECK STIFFNESS OR MALPOSITION

TABLE 44.2

COMMON CAUSES OF NECK STIFFNESS OR MALPOSITION

Neck Stiffness Associated with Infectious/Inflammatory Conditions

Potentially Life-threatening Causes

Bacterial meningitis has become a very uncommon childhood disease in the United States, however, it is still the most important infectious cause of neck stiffness (see Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies). In the HiB and PCV13 vaccine era, the most common bacterial pathogens causing meningitis after infancy are Streptococcus pneumoniae (including non–vaccine-type strains) and Neisseria meningitidis. Children with meningitis typically present with fever and headache with neck stiffness on physical examination. These findings may not be apparent in young infants or conditions with less inflammatory response (i.e., meningococcal meningitis). Torticollis has also been reported in patients with bacterial meningitis, although less commonly.

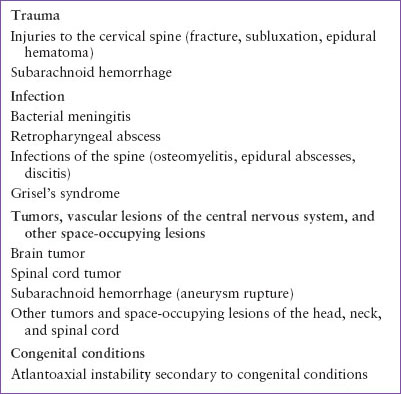

TABLE 44.3

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF NECK STIFFNESS OR MALPOSITION

Retropharyngeal Abscess. There are several other important infectious processes for which neck stiffness and fever usually are the presenting signs. Retropharyngeal abscess is an infection that occupies the potential space between the posterior pharyngeal wall and the anterior border of the cervical vertebrae. Most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococcus, and oral anaerobes, these infections typically present with clinical toxicity, drooling, and sometimes stridor. Neck pain and/or stiffness are the presenting clinical findings in approximately two-thirds of these children. Limitation of neck extension and torticollis are particularly common. Lateral radiographs of the neck can be helpful in making the diagnosis and will reveal soft tissue swelling anterior to the upper cervical vertebral bodies. When radiographs are limited, however, due to inadequate neck extension or failure to obtain the image during inspiration, or when a positive finding of a widened prevertebral space is noted, CT imaging with contrast is required.

Infections of the Spine. Infectious processes involving the spine (osteomyelitis, epidural abscess, discitis) in children can involve the cervical region, although they occur most commonly in the thoracic and lumbar areas. Localized pain, fever, and elevation of inflammatory markers including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein generally accompany these infections.

Cervical vertebral osteomyelitis may lead to neck stiffness. Vertebral osteomyelitis is usually bacterial in origin (most commonly caused by S. aureus) but may be caused by mycobacteria as well. If the cervical spine is involved, radiographs of this area may reveal destruction of the vertebral body, local soft tissue swelling, or narrowing of the disc space. MRI is the imaging modality of choice and may reveal abnormalities of the spine before bony destruction is visible on plain radiography.

Although uncommon, spinal epidural abscesses are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. When these abscesses occur in the cervical region, severe neurologic deficits may occur, and emergent neurosurgical consultation is essential.

Discitis is uncommon in children; however, cases of cervical discitis have been reported. This disease is generally seen in children younger than 3 years of age. The most commonly identified microbiologic organism is S. aureus, although bacterial cultures are commonly negative and the cause has been debated. When evaluating for this condition, MRI is indicated.

Generally Non–life-threatening Causes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree