Managing nausea and vomiting

Adequate relief of these symptoms requires systematic assessment of the patient to diagnose the most likely cause(s). If the cause can be reversed—for example, with surgery to reverse gastrointestinal obstruction or measures to correct hypercalcaemia—then an antiemetic may be required only temporarily. In palliative care, however, the cause is often irreversible and a long term antiemetic strategy is required.

Prescribing antiemetic drugs is only part of such a strategy. Attention to the patient’s understanding of the meaning of the symptoms, dealing with anxiety (which can cause or exacerbate nausea), and helping the patient to have realistic expectations about symptom management are important components of the strategy. Complementary therapies may have a role—for instance, there is good evidence for the efficacy of acupuncture in the management of nausea.

Antiemetics and other useful drugs

Pharmacological management of nausea and vomiting includes the use of drugs to block the emetogenic reflex in the brain stem (antiemetics), drugs to promote peristalsis in the upper gastrointestinal tract (prokinetic agents), drugs to reduce the volume of gastrointestinal secretions (antisecretory agents), and adjuvant drugs—for example, corticosteroids.

Choosing an antiemetic

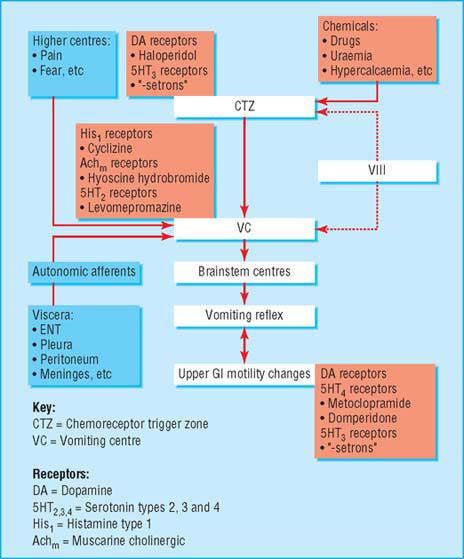

Antiemetic drugs work by binding to specific receptor sites in the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) or vomiting centre (VC) in the brain stem. At each site there are several receptors; the more strongly the drug binds to its receptor, the more potent its antiemetic activity.

The most potent antiemetic at the CTZ is the dopamine antagonist haloperidol. At the VC, the non-sedating antihistamine cyclizine and the antimuscarinic hyoscine hydrobromide have similar efficacy, but the side effects of centrally acting antimuscarinics reduce their usefulness and makes cyclizine the drug of choice.

Levomepromazine is a phenothiazine with affinity for receptors at both the CTZ and the VC. Although its binding affinity is lower than cyclizine or haloperidol for the same receptors, it may be a useful broad spectrum antiemetic. It must be used in low doses to avoid sedation and hypotension.

Triggers to nausea and vomiting: pathways, receptors, and recommended antiemetics

- Acting at CTZ: haloperidol, metoclopramide, levomepromazine

- Acting at vomiting centre: cyclizine, hyoscine hydrobromide, levomepromazine

- Acting on 5HT3 receptors (for nausea and vomiting induced only by chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgery): ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron

| Antisecretory agents | Prokinetic agents |

|

|

- Cinnarizine

- Dimenhydrinate

- H2 antagonists—for example, ranitidine, cimetidine

- Proton pump inhibitors—for example, omeprazole, lansoprazole

- Prostaglandin analogues—for example, misoprostol

- Corticosteroids

- Cannabinoids: nabilone

*Cardiotoxic: cisapride must be ordered on a named patient basis in the UK

Metoclopramide has a lower affinity for CTZ dopamine receptors than haloperidol and so is less effective as an antiemetic. It has prokinetic activity because of its action on receptors in the gastrointestinal tract, and this is its major use in palliative care.

Steps to good management of symptoms

- Thorough assessment: history, examination, biochemistry, imaging, microbiology, and other investigations may all be required to establish a probable cause for nausea and/or vomiting

- Having identified a probable cause, determine what neurotransmitter receptors are likely to be involved

- Choose an antiemetic that is a specific antagonist to that neuroreceptor

- Give this antiemetic by a route that will ensure it will reach its target: in practical terms, this means avoiding the oral route (even in the absence of vomiting) until nausea has been settled for at least 24 hours

- Reassess. If nausea persists, there may be an additional trigger that has not been identified. Continue the first antiemetic while reassessing and introducing a second antiemetic acting at a different site in the brain stem

- Decide whether any of the triggers can be reversed. This depends both on the trigger and the patient’s performance status or preference about other treatment options—for example, surgery, radiotherapy, dialysis

- Once nausea is controlled, plan how control will be maintained—for example, oral antiemetics, syringe driver, acupuncture, etc.

Non-drug approaches to palliation

Psychological techniques—Studies in people undergoing chemotherapy have shown that patients can learn progressive muscle relaxation and use mental imagery to increase their relaxation and reduce their nausea. Cognitive therapy has also been used to help to reduce the emotional distress arising from physical symptoms in advanced cancer. Hypnotherapy can help to reduce the sensation of nausea and the perceived duration of nausea.

Acupuncture and acupressure have both been shown to augment the effects of antiemetic drugs during chemotherapy and to reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can be used as an alternative to traditional acupuncture needles at the P6 acupuncture point, and this is more practical for patients to use themselves.

Management of specific nausea and vomiting syndromes

Gastric stasis

Reduction in gastric emptying may be caused by opioids, mucosal inflammation (NSAIDs, stress, tumour), anticholinergic drugs (including side effects of tricyclic antidepressants and antipsychotics), raised intra-abdominal pressure (ascites, hepatomegaly), or occasionally by encroachment of tumour on the gastric outlet (such as gastroduodenal tumours, mass in head of pancreas).

Autonomic failure may be a feature of end stage cancer, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, and AIDS and can allow pooling of gastric secretions in a patulous stomach, with regurgitation and posseting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree