CHAPTER 123

Myofascial Pain Syndrome, Fibromyalgia

(Trigger Points)

Presentation

In myofascial pain syndrome, the patient, who is generally 25 to 50 years of age, will be troubled by the gradual onset of localized or regional unilateral fibromuscular pain that at times can be immobilizing. There may be a history of acute strain, or a history of predisposing activities, such as holding a telephone receiver between the ear and shoulder to free the arms, prolonged bending, poor postural habits, repetitive motions, and heavy lifting using poor body mechanics. The areas most commonly affected are the axial muscles, used to maintain posture, which include the posterior muscles of the neck and scapula and the soft tissues lateral to the thoracic and lumbar spine.

Careful examination of the painful region will reveal one or more “trigger points,” which, when firmly pressed with an examining finger, will cause the patient to wince, cry out, or jump with pain. The underlying muscle may contain a small (2- to 5-mm) firm knot, nodule, or taut band of muscle fibers that produces the exquisitely tender trigger point and reproduces the pain of their chief complaint. Pain is often referred in a radicular pattern that may mimic the pain of cervical or lumbar disc herniation.

The patient with fibromyalgia, on the other hand, has widespread, bilateral symmetric musculoskeletal pain that is associated with multiple “tender points” on palpation and that do not cause any radiation of pain. This patient is often depressed or under emotional or physical stress and may have associated chronic fatigue with disturbed sleep, irritable bowel syndrome, cognitive difficulties, headache, morning stiffness, and sensations of numbness or swelling in the hands and feet. Other comorbid conditions might include irritable bladder symptoms, temporomandibular joint syndrome, myofascial pain syndrome, restless leg syndrome, and affective disorders. Cold or hot weather may be one of the precipitating causes of pain.

In both syndromes, most affected patients are women. Also, the pain is nonarticular, and there are no abnormal vital signs and no swelling, erythema, or heat over the painful areas.

What To Do:

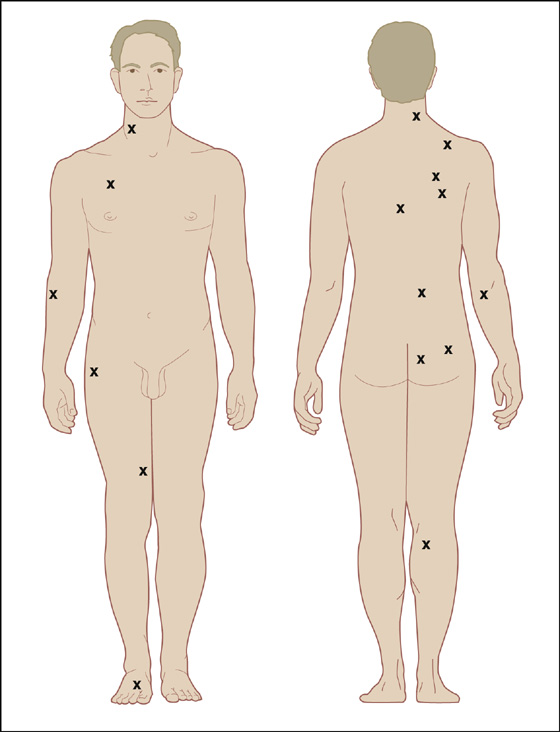

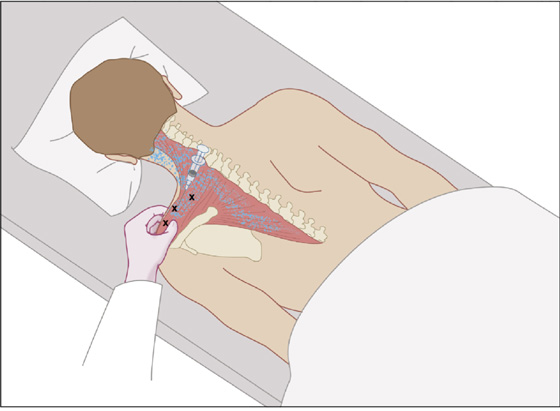

Obtain a careful history and perform a general physical examination with special attention to the painful area. Myofascial pain is local or referred regional muscular pain of short (days) or prolonged (months) duration, often causing head, neck, shoulder, upper and lower back, buttock, and leg pain and associated with trigger points, as described earlier. The patient can usually point to the pain with one finger (Figure 123-1).

Obtain a careful history and perform a general physical examination with special attention to the painful area. Myofascial pain is local or referred regional muscular pain of short (days) or prolonged (months) duration, often causing head, neck, shoulder, upper and lower back, buttock, and leg pain and associated with trigger points, as described earlier. The patient can usually point to the pain with one finger (Figure 123-1).

Figure 123-1 Most frequent locations of myofascial trigger points. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

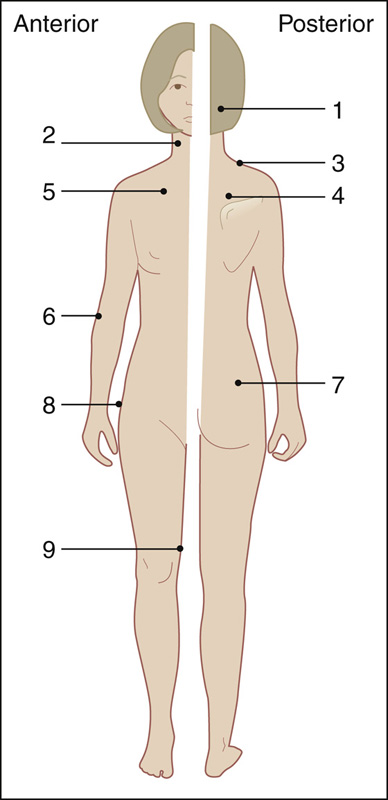

The pain of fibromyalgia is widespread (bilateral, above and below the waist), prolonged (>3 months), and associated with approximately 11 of 18 possible tender points (Figure 123-2). These tender points are predictable, and, unlike trigger points, they do not cause radiation of pain or have an underlying small tender muscular knot. The associated coexisting conditions mentioned earlier help to support this diagnosis.

The pain of fibromyalgia is widespread (bilateral, above and below the waist), prolonged (>3 months), and associated with approximately 11 of 18 possible tender points (Figure 123-2). These tender points are predictable, and, unlike trigger points, they do not cause radiation of pain or have an underlying small tender muscular knot. The associated coexisting conditions mentioned earlier help to support this diagnosis.

Figure 123-2 Location of nine bilateral (18) tender point sites for the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. 1 = suboccipital muscle insertions; 2 = cervical, at the anterior aspects of the intransverse spaces at C5-7; 3 = trapezius, at the midpoint of the upper border; 4 = supraspinatus, at the origin, above the scapular spine near the medial border; 5 = second rib, at the costochondral junction; 6 = lateral epicondyle, 2 cm distal to the epicondyle; 7 = gluteal, in the upper outer quadrant of the buttock; 8 = greater trochanter, just posterior to the trochanteric prominence; 9 = knee, at the medial fat pad proximal to the joint line. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Other conditions should be considered, such as medication-induced myalgias (e.g., statins, colchicines, corticosteroids, antimalarial drugs), connective tissue diseases (e.g., dermatomyositis, polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis), hypothyroidism and other endocrine disorders, and cancer. In addition, evaluate for true radicular pain with a neurologic examination, and, if indicated, straight-leg raising.

Other conditions should be considered, such as medication-induced myalgias (e.g., statins, colchicines, corticosteroids, antimalarial drugs), connective tissue diseases (e.g., dermatomyositis, polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis), hypothyroidism and other endocrine disorders, and cancer. In addition, evaluate for true radicular pain with a neurologic examination, and, if indicated, straight-leg raising.

With any suspicion that an underlying systemic illness exists, obtain appropriate radiographs and laboratory tests, such as an erythrocyte sedimentation rate, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and thyroid-stimulating hormone. These and all other studies should be normal in both myofascial and fibromyalgia pain syndrome.

With any suspicion that an underlying systemic illness exists, obtain appropriate radiographs and laboratory tests, such as an erythrocyte sedimentation rate, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and thyroid-stimulating hormone. These and all other studies should be normal in both myofascial and fibromyalgia pain syndrome.

When a trigger point is found, have the patient maintain a comfortable, relaxed position. Map out its exact location (point of maximum tenderness) and place an “X” over the site with a marker or ballpoint pen. If the trigger point is diffuse, there is no need to outline its location.

When a trigger point is found, have the patient maintain a comfortable, relaxed position. Map out its exact location (point of maximum tenderness) and place an “X” over the site with a marker or ballpoint pen. If the trigger point is diffuse, there is no need to outline its location.

When myofascial pain is suspected but trigger points are diffuse, unless contraindicated, prescribe a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen sodium (Naprosyn), 250 mg, two tablets stat then one qid, or ibuprofen (Motrin), 800 mg stat then 600 mg qid × 5 days. A benzodiazepine such as lorazepam (Ativan), 1 mg qid, may also be helpful.

When myofascial pain is suspected but trigger points are diffuse, unless contraindicated, prescribe a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen sodium (Naprosyn), 250 mg, two tablets stat then one qid, or ibuprofen (Motrin), 800 mg stat then 600 mg qid × 5 days. A benzodiazepine such as lorazepam (Ativan), 1 mg qid, may also be helpful.

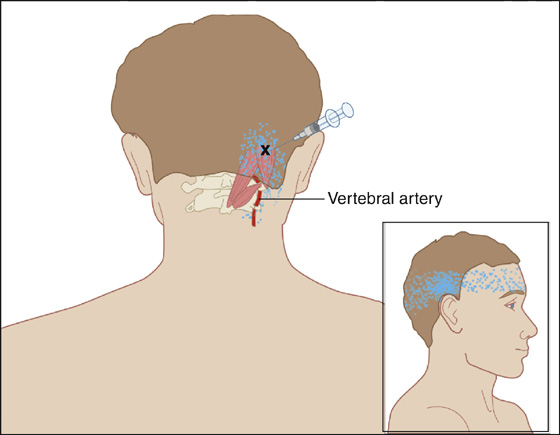

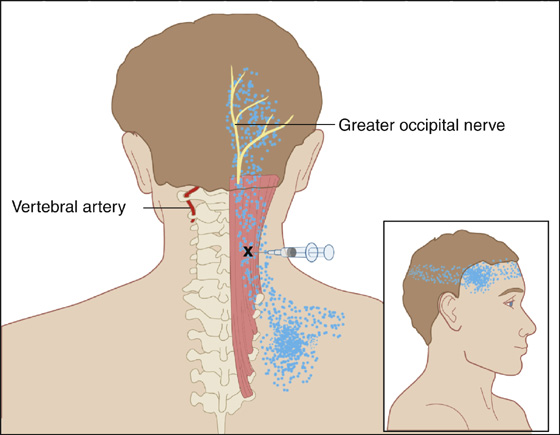

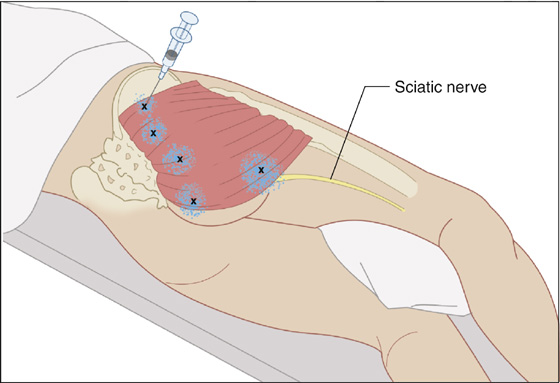

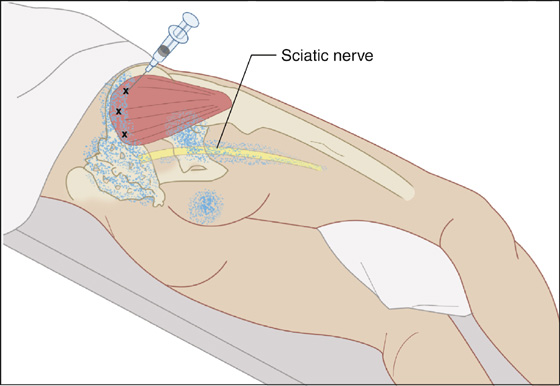

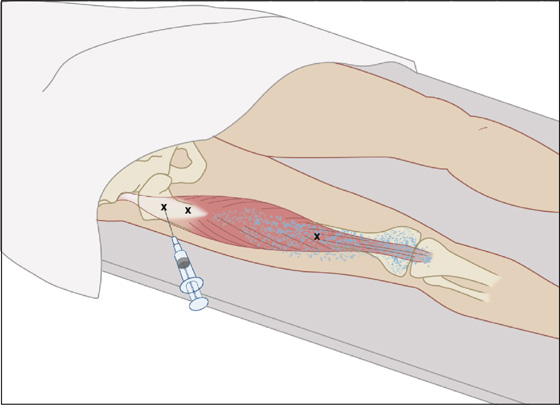

When a focal trigger point is present, suggest that the patient may get immediate relief with an injection. If the patient is willing, using proper aseptic technique and a 25- or 27-gauge, 1¼- to 1½-inch needle, inject through the mark you placed on the skin, directly into the painful site (Figures 123-3 to 123-13). Use 5 to 10 mL of 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) or longer-acting 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine) with or without 20 to 40 mg of methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol) or 2 to 5 mg of triamcinolone (Aristospan). Attempt aspiration to be sure you are not in a blood vessel or pleural cavity and then “fan” the needle in all directions while injecting the trigger point. Advise the patient before the procedure that there may be intensification of the pain before relief. Intensification of the pain with or without radiation, while injecting slowly, is a good indicator that the needle is in the precise trigger point location. Inject most of the anesthetic into this most painful site. In addition, massage the area after the injection is complete to ensure total coverage. Within a few minutes the patient will often get complete or near-complete pain relief, which helps to confirm the diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome. Inform the patient that there will be approximately 1 day of muscular soreness after the anesthetic wears off. The beneficial effect of this injection may last for weeks or months. A supplementary 5-day course of NSAIDs is optional.

When a focal trigger point is present, suggest that the patient may get immediate relief with an injection. If the patient is willing, using proper aseptic technique and a 25- or 27-gauge, 1¼- to 1½-inch needle, inject through the mark you placed on the skin, directly into the painful site (Figures 123-3 to 123-13). Use 5 to 10 mL of 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) or longer-acting 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine) with or without 20 to 40 mg of methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol) or 2 to 5 mg of triamcinolone (Aristospan). Attempt aspiration to be sure you are not in a blood vessel or pleural cavity and then “fan” the needle in all directions while injecting the trigger point. Advise the patient before the procedure that there may be intensification of the pain before relief. Intensification of the pain with or without radiation, while injecting slowly, is a good indicator that the needle is in the precise trigger point location. Inject most of the anesthetic into this most painful site. In addition, massage the area after the injection is complete to ensure total coverage. Within a few minutes the patient will often get complete or near-complete pain relief, which helps to confirm the diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome. Inform the patient that there will be approximately 1 day of muscular soreness after the anesthetic wears off. The beneficial effect of this injection may last for weeks or months. A supplementary 5-day course of NSAIDs is optional.

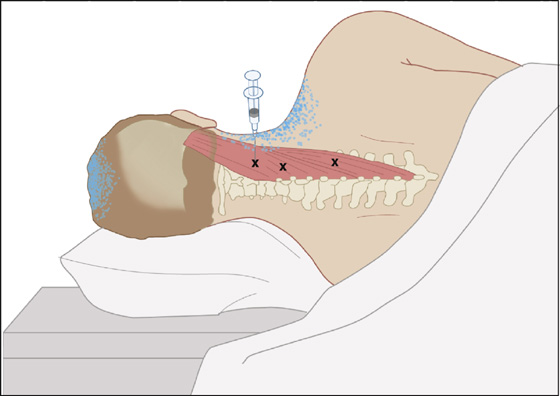

Figure 123-3 Suboccipital muscle. Injection of trigger point (X) in the obliquus capitis superior muscle with the patient in the prone position. Injection is localized directly over the trigger point and the superior portion of the occipital area to avoid the vertebral artery. The occipital triangle and vertebral artery are noted. The pain pattern is shown by stippling.(Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Figure 123-4 Posterior cervical muscles (semispinalis and multifidi). Injection of trigger point in the right posterior cervical muscles (X). The greater occipital nerve is visualized. Anatomic landmarks are noted in addition to visualization of the left vertebral artery. Avoid the vertebral artery by injecting above or below the vertebral artery area. Aspirate prior to injection. The pain pattern is shown by stippling. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Figure 123-5 Splenius capitis and splenius cervicis. Injection of trigger points (Xs) in the right splenius capitis and cervicis with the patient lying on the uninvolved side. Avoid the vertebral artery. Aspirate prior to injection. Anatomic landmarks are noted. The trigger-point pattern is shown by stippling.(Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

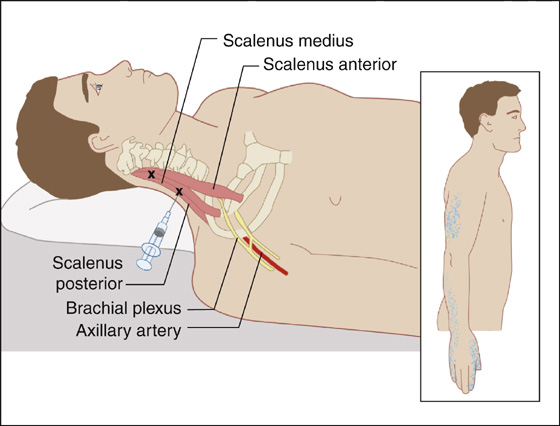

Figure 123-6 Scalene muscles. Injection of the scalenus medius muscle trigger points (Xs). The patient is supine, the head turned away from the area of pain. Anatomic landmarks are noted, including axillary artery and lateral chord. The referred pain pattern is shown by stippling. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

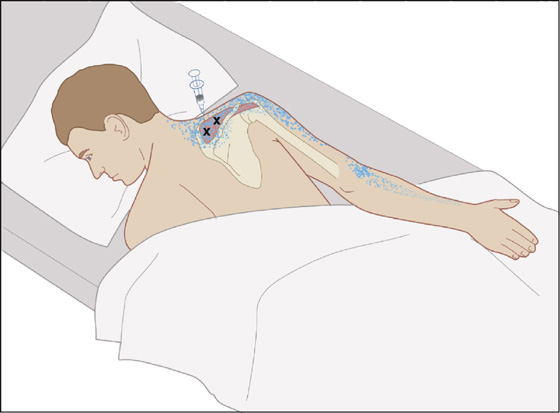

Figure 123-7 Supraspinatus. Injection of trigger points (Xs) in the right supraspinatus with the patient prone. The needle is directed directly over the supraspinous fossa of the scapula to avoid penetrating the rib cage. Anatomic landmarks are noted. The pain pattern is shown by stippling.(Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Figure 123-8 Serratus posterior superior. Injection of trigger point (X) in the right serratus posterior superior. Localize the trigger point by palpation and direct the needle in the direction of a rib and tangentially in relation to chest wall to avoid entering the intercostal space. Aspirate before injection. Trigger points in the region of muscle insertion are more easily palpated with abduction of the right scapula. Observe precautions to prevent pneumothorax. Inset, trigger-point pain pattern (stippling). (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Figure 123-9 Trapezius. Injection for trigger points (Xs) in the left trapezius with the patient prone. The upper portion of the left trapezius is grasped between the thumb, index, and middle fingers and is elevated to avoid penetrating the apex of the lung. Several entries are usually necessary to treat all trigger points that are present. Aspirate prior to injection. The pain pattern is shown by stippling. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

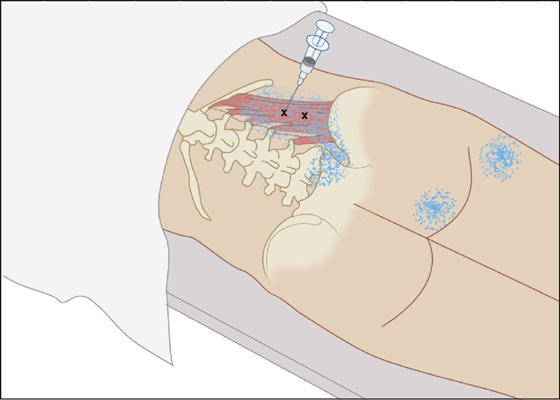

Figure 123-10 Gluteus maximus. Injection of trigger points (Xs) in the gluteus maximus. Anatomic landmarks are noted. Avoid the sciatic nerve. The pain pattern is shown by stippling. Injection may be performed with the patient in the prone or side-lying position. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Figure 123-11 Gluteus medius. Injection of trigger points in the right gluteus medius. Multiple trigger points (Xs) are noted. Anatomic skeletal landmarks are shown together with the sciatic nerve. The patient is positioned lying on the uninvolved side. Injection may also be performed with the patient prone. The pain pattern is noted by stippled area.(Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Figure 123-12 Rectus femoris. Injection of trigger points (Xs) in the right rectus femoris. Note trigger points in the area of origin and distally toward the area of insertion. The patient is supine. The trigger point pain pattern is shown by stippling. Anatomic landmarks are noted. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

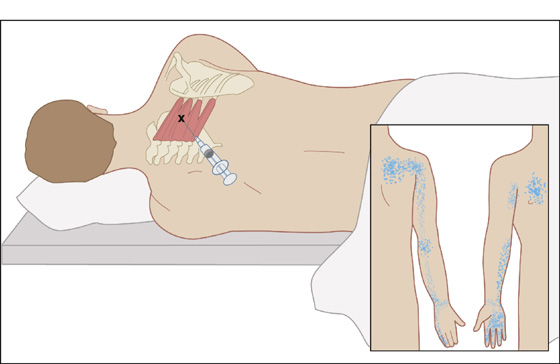

Figure 123-13 Quadratus lumborum. Injection of trigger points (Xs) in the right quadratus lumborum with the patient in the prone position. Injection may also be performed with the patient lying on the uninvolved side. The trigger point pain pattern is shown by stippling. Direct the needle tangentially or parallel to the frontal plane of the patient. (Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Secondary trigger points may develop in neighboring muscles as a result of stress and muscle spasm. It is common for patients to experience the pain of a secondary trigger point after a primary trigger point is eliminated. These trigger points can be treated in the same manner, either at the same visit or at an early follow-up visit if the symptoms persist.

Secondary trigger points may develop in neighboring muscles as a result of stress and muscle spasm. It is common for patients to experience the pain of a secondary trigger point after a primary trigger point is eliminated. These trigger points can be treated in the same manner, either at the same visit or at an early follow-up visit if the symptoms persist.

Moist, hot compresses and massage may also be comforting to the patient after discharge.

Moist, hot compresses and massage may also be comforting to the patient after discharge.

Patients with the diffuse symptoms of fibromyalgia usually will not benefit from trigger point injection or NSAIDs. When other causes of such pain have been adequately ruled out, antidepressants, most commonly amitriptyline (Elavil), 10 to 50 mg qd, improve symptoms for up to several months. The muscle relaxant cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), which is structurally similar to the tricyclic antidepressants, has also been found to be beneficial in doses of 15 to 45 mg/day divided tid. Tramadol (Ultram), 50 to 100 mg q4-6h (not to exceed 400 mg/day), is an analgesic that has also been found to benefit patients with fibromyalgia.

Patients with the diffuse symptoms of fibromyalgia usually will not benefit from trigger point injection or NSAIDs. When other causes of such pain have been adequately ruled out, antidepressants, most commonly amitriptyline (Elavil), 10 to 50 mg qd, improve symptoms for up to several months. The muscle relaxant cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), which is structurally similar to the tricyclic antidepressants, has also been found to be beneficial in doses of 15 to 45 mg/day divided tid. Tramadol (Ultram), 50 to 100 mg q4-6h (not to exceed 400 mg/day), is an analgesic that has also been found to benefit patients with fibromyalgia.

Aerobic exercise and warm compresses improve function and reduce pain in persons with fibromyalgia.

Aerobic exercise and warm compresses improve function and reduce pain in persons with fibromyalgia.

Provide follow-up care for all patients in the event that their symptoms do not clear and they require further diagnostic evaluation and therapy.

Provide follow-up care for all patients in the event that their symptoms do not clear and they require further diagnostic evaluation and therapy.

What Not To Do:

Do not order radiographs or laboratory tests for myofascial pain that is localized and relieved by trigger point injection.

Do not order radiographs or laboratory tests for myofascial pain that is localized and relieved by trigger point injection.

Do not attempt to inject a very diffuse trigger point (more than 2 cm2) or multiple scattered tender points as found in true fibromyalgia syndrome. Results are generally unsatisfactory.

Do not attempt to inject a very diffuse trigger point (more than 2 cm2) or multiple scattered tender points as found in true fibromyalgia syndrome. Results are generally unsatisfactory.

Do not inject trigger points in the presence of systemic or local infection, in patients with bleeding disorders, in patients on anticoagulants, or in patients who appear to be or feel ill.

Do not inject trigger points in the presence of systemic or local infection, in patients with bleeding disorders, in patients on anticoagulants, or in patients who appear to be or feel ill.

Do not prescribe narcotic analgesics or systemic steroids. They are no more effective than the abovementioned therapy and add side effects and the risk for dependence.

Do not prescribe narcotic analgesics or systemic steroids. They are no more effective than the abovementioned therapy and add side effects and the risk for dependence.

Do not prescribe NSAIDs to patients with fibromyalgia. They have been found to be no more effective than placebo in this group of patients.

Do not prescribe NSAIDs to patients with fibromyalgia. They have been found to be no more effective than placebo in this group of patients.

Emergency physicians and other acute care clinicians often see patients with trigger points associated with simple self-limiting regional myofascial pain syndromes, which appear to arise from muscles, muscle–tendon junctions, or tendon–bone junctions. Myofascial disease can result in severe pain, but it is typically in a limited distribution, without the systemic feature of fatigue, and without the multiple somatic complaints of fibromyalgia. Trigger-point injection therapy, the treatment of choice for trigger points according to many, has gained widening acceptance in mainstream medicine. When symptoms recur or persist after this basic therapy or are accompanied by generalized complaints, acute care clinicians should refer these patients to a rheumatologist or primary care physician for follow-up and continued management.

When the quadratus lumborum muscle is involved (see Figure 123-13), there is often confusion whether or not the patient has a renal, abdominal, or pulmonary ailment. The reason for this is the muscle’s proximity to the flank and abdomen, as well as its attachment to the twelfth rib, which, when tender, can create pleuritic symptoms. A careful physical examination reproducing symptoms through palpation, active contraction, and passive stretching of this muscle can save this patient from a multitude of laboratory and radiograph studies.

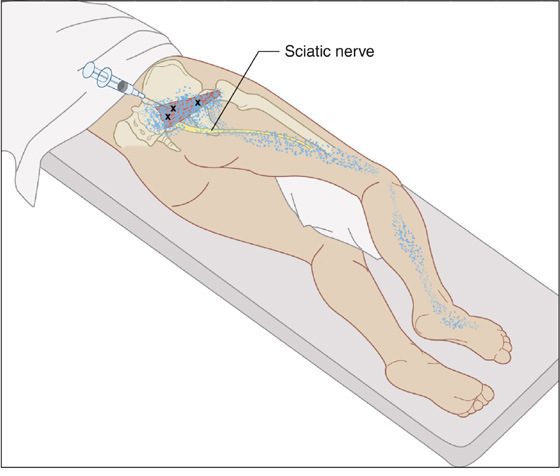

Another affected muscle that often confuses and misleads clinicians is the piriformis (Figure 123-14). Piriformis syndrome is an uncommon and often undiagnosed cause of buttock and leg pain. It may be caused by anatomic abnormalities of the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve resulting in irritation of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis.

Figure 123-14 Piriformis. Injection of trigger points in the right piriformis muscle (Xs). The sciatic nerve is shown in addition to anatomic details. Injection is performed with the patient lying on the uninvolved side. A pillow is placed between the knees. The hip is flexed. The pain pattern is shown by stippling.(Adapted from Rachlin E, Rachlin I: Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management, ed 2. St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

The typical patient with piriformis syndrome complains of buttock pain with or without radiation to the posterior thigh that sometimes extends below the knee to the calf, resembling typical sciatica and causes difficulty with walking. The cardinal characteristic of the syndrome is sitting intolerance secondary to intense buttock pain. Gluteal atrophy may occur.

Buttock tenderness in the region of the greater sciatic foramen is present in almost all patients, and buttock pain is elicited when the patient lifts and holds the knee several inches off the examination table. There may be moderate relief of pain by applying traction on the affected extremity with the patient in the supine position. A tender sausage-shaped mass may be palpated over the piriformis muscle.

A complete neurologic examination should be performed to test motor power, sensory function, and reflexes of the lower extremities to help rule out spinal causes of sciatic pain. One should also consider intrapelvic diseases, such as tumors and endometriosis, as a possible cause of sciatic pain.

Conservative treatment of piriformis syndrome consists of prescribing NSAIDs, analgesics, and muscle relaxants and providing physical therapy, which includes stretching the piriformis muscle with internal rotation and hip adduction and flexion.

More aggressive therapy includes local injection of anesthetic and corticosteroids that may reconfirm the diagnosis through therapeutic success (see Figure 123-14). This may be repeated twice with recurrent pain. If this fails, surgery can be considered.

The most likely cause of chronic diffuse myalgia is fibromyalgia. Among adults who seek medical attention for fibromyalgia, less than one third recover within 10 years of onset. Symptoms tend to remain stable or improve over time.

Although fibromyalgia was long believed to be primarily a muscle disease, research has not found any significant pathologic or biochemical abnormalities in muscle tissue. Many researchers now believe that the disease is caused by abnormalities in central nervous system function. This would suggest that the pain of fibromyalgia is in part because of a decrease in the threshold for pain perception and tolerance experienced by these patients. Fibromyalgia patients also appear to experience pain amplification because of abnormal sensory processing in the central nervous system.

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia is made by meeting the criteria of having widespread musculoskeletal pain for 3 months or longer and having 11 or more tender points among 18 potential sites defined by the American College of Rheumatology (see Figure 123-2). Some patients may not have an adequate number of tender points to make the diagnosis, but when typically associated symptoms are present, these patients should be treated for fibromyalgia.

Education, reassurance, psychological support, and reminders to exercise regularly are important in all follow-up visits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree