Trauma is the leading cause of pediatric deaths in developed countries; most children suffer significant morbidity following major trauma.

Trauma is the leading cause of pediatric deaths in developed countries; most children suffer significant morbidity following major trauma. Blunt trauma is more frequent than penetrating trauma, although the latter is associated with a higher mortality rate.

Blunt trauma is more frequent than penetrating trauma, although the latter is associated with a higher mortality rate. The ABCDs (airway, breathing, circulation, and disability) are the focus of the primary survey and mandate appropriate interventions and continued reassessment during the “golden hour” (or “platinum half hour”) following injury.

The ABCDs (airway, breathing, circulation, and disability) are the focus of the primary survey and mandate appropriate interventions and continued reassessment during the “golden hour” (or “platinum half hour”) following injury. Respiratory failure is a frequent complication of major pediatric trauma, whereas hypotension is less common and a late finding (compared with adults).

Respiratory failure is a frequent complication of major pediatric trauma, whereas hypotension is less common and a late finding (compared with adults). The goal of the secondary survey is to definitively evaluate the injured child, and it should proceed concurrently with ongoing resuscitation efforts by a multidisciplinary team; laboratory examinations are an important component.

The goal of the secondary survey is to definitively evaluate the injured child, and it should proceed concurrently with ongoing resuscitation efforts by a multidisciplinary team; laboratory examinations are an important component. Common visceral injuries in children include contusions, hematomas, and lacerations of the lungs, liver, spleen, or kidneys, as well as pneumothorax, hemothorax, rib fractures, and gastrointestinal tract injury.

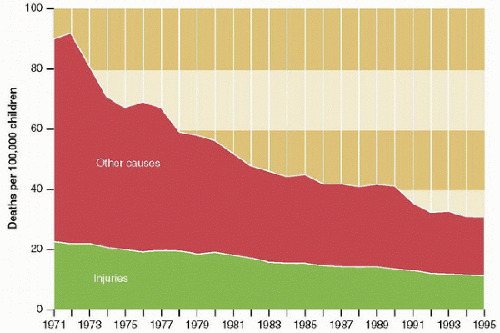

Common visceral injuries in children include contusions, hematomas, and lacerations of the lungs, liver, spleen, or kidneys, as well as pneumothorax, hemothorax, rib fractures, and gastrointestinal tract injury. (Table 30.1). During the last three decades in the United States, the population-based mortality rate for unintentional pediatric injury has fallen by more than 50%, although it remains the most common cause of death for all pediatric patients in the most recent year for which statistics are available (2009) (1), followed in older adolescents by homicide and suicide. Indeed, although mortality rates for the leading causes of pediatric death have declined in developed countries, the decline is least for trauma (Fig. 30.2). Most pediatric deaths from trauma are associated with motor vehicles and occur prior to hospital admission. The morbidity of pediatric trauma increases with increasing severity of injury and is manifested frequently by functional limitations following major injury; the overall cost is difficult to estimate, although it is likely enormous.

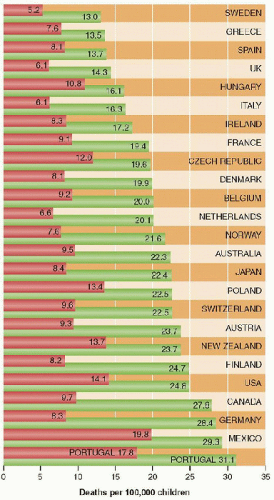

(Table 30.1). During the last three decades in the United States, the population-based mortality rate for unintentional pediatric injury has fallen by more than 50%, although it remains the most common cause of death for all pediatric patients in the most recent year for which statistics are available (2009) (1), followed in older adolescents by homicide and suicide. Indeed, although mortality rates for the leading causes of pediatric death have declined in developed countries, the decline is least for trauma (Fig. 30.2). Most pediatric deaths from trauma are associated with motor vehicles and occur prior to hospital admission. The morbidity of pediatric trauma increases with increasing severity of injury and is manifested frequently by functional limitations following major injury; the overall cost is difficult to estimate, although it is likely enormous. Reductions in the rates of pediatric trauma morbidity and mortality are the result of concerted efforts during the last few decades, which have involved research, education,

Reductions in the rates of pediatric trauma morbidity and mortality are the result of concerted efforts during the last few decades, which have involved research, education, legislation, and an investment in medical services at all levels. Further declines in pediatric trauma morbidity and mortality in the United States will require an even broader and more vigorous public health approach, probably modeled after some of the more successful systems in European countries such as Sweden, Italy, the UK, and the Netherlands.

TABLE 30.1 INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY OF PEDIATRIC TRAUMA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

nearly half, or 3%, are due to child abuse) (4). Blunt injuries outnumber penetrating injuries in children by a ratio of 12:1, a ratio that has decreased in recent years. While blunt injuries are more common, penetrating injuries are more lethal.

nearly half, or 3%, are due to child abuse) (4). Blunt injuries outnumber penetrating injuries in children by a ratio of 12:1, a ratio that has decreased in recent years. While blunt injuries are more common, penetrating injuries are more lethal. Injury mechanism is the main predictor of injury pattern (Table 30.2). Pedestrian motor vehicle trauma may result in the Waddell triad of injuries to the head, torso, and lower extremities, while occupant injuries include head, face, and neck trauma in unrestrained passengers, and cervical spine injuries, bowel disruption or hematoma, and Chance fractures of the spine in restrained passengers. Bicycle trauma results in head injury in unhelmeted riders and upper extremity and upper abdominal injuries (results from contact with the handlebar). Low falls, the most common cause of childhood injury, rarely produce significant trauma, but high falls (from the second story or higher) are associated with serious head injuries, with the addition of long-bone fractures (at the third story), and intrathoracic and intra-abdominal injuries (at the fifth story, the height from which 50% of children can be expected to die) (5). With the growing popularity of extreme sports (including extreme skiing and surfing, inline skating, mountain bicycling, rock climbing, skateboarding, snowboarding, and ultraendurance racing) in which risk is very high and often underappreciated, patterns of adolescent traumatic injury are likely to change.

Injury mechanism is the main predictor of injury pattern (Table 30.2). Pedestrian motor vehicle trauma may result in the Waddell triad of injuries to the head, torso, and lower extremities, while occupant injuries include head, face, and neck trauma in unrestrained passengers, and cervical spine injuries, bowel disruption or hematoma, and Chance fractures of the spine in restrained passengers. Bicycle trauma results in head injury in unhelmeted riders and upper extremity and upper abdominal injuries (results from contact with the handlebar). Low falls, the most common cause of childhood injury, rarely produce significant trauma, but high falls (from the second story or higher) are associated with serious head injuries, with the addition of long-bone fractures (at the third story), and intrathoracic and intra-abdominal injuries (at the fifth story, the height from which 50% of children can be expected to die) (5). With the growing popularity of extreme sports (including extreme skiing and surfing, inline skating, mountain bicycling, rock climbing, skateboarding, snowboarding, and ultraendurance racing) in which risk is very high and often underappreciated, patterns of adolescent traumatic injury are likely to change.from severe military trauma via better control of hemorrhage achieved by the application of tourniquets following traumatic amputation as well as vigorous replacement of coagulation factors. Application of experience from battlefield resuscitation is likely to help improve outcome for civilian trauma.

TABLE 30.2 COMMON INJURY MECHANISMS AND CORRESPONDING INJURY PATTERNS IN CHILDHOOD TRAUMA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

exciting or inhibiting the medullary vasoconstrictor and vagal parasympathetic centers, with resultant changes in vasomotor tone, chronotropy, and inotropy. Maximum sympathetic vasoconstriction may occur, at least for the first few minutes following trauma that results in global brain ischemia. Other responses to the stress of trauma include the release of angiotensin by the kidneys, cortisol, and aldosterone by the adrenal glands, vasopressin by the posterior pituitary gland, and various local compensatory mechanisms, which help to contract circulation or shift fluid into the intravascular compartment in the presence of diminished blood volume. Tissue injury may also activate cascades that contribute to the stress response and that include complement, cytokines, eicosanoids, histamine, kinins, nitric oxide, serotonin, and a variety of hormonal mediators.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree