Mouth and Throat Infections

Daniel Z. Aronzon MD

INTRODUCTION

Sore throats represent a leading cause of visits to the primary care office for children and adolescents. After otitis media, upper respiratory infections (URIs), and bronchitis, it is the fourth leading diagnosis prompting a prescription for antibiotics (Nyquist et al., 1998). Fortunately, with the proliferation of rapid streptococcal antigen testing and the ease and availability of throat cultures, little or no reason exists for diagnostic uncertainty and unnecessary prescription of antibiotics.

In general, tonsillitis, pharyngotonsillitis, and pharyngitis all mean the same thing, because throat infections are never so ideally localized. For the purposes of this discussion, the term acute pharyngitis is used to denote all three.

Etiologically and practically, acute pharyngitis can be divided into two broad categories: viral and bacterial. Viruses as a group account for 15% to 40% of cases of acute pharyngitis in children and 30% to 60% of cases in adolescents. Rhinovirus, adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, coronovirus, enteroviruses (EVs), herpes simplex, Epstein-Barr, and cytomegalovirus are commonly implicated (Pichichero, 1998). Only acute pharyngitis caused by the EV group, herpes simplex, Epstein-Barr, and cytomegalovirus is clinically distinctive enough to warrant specific discussion. Other causes may be responsible for a wide variety of clinical diseases but are indistinguishable with respect to pharyngeal findings and therefore are not discussed further.

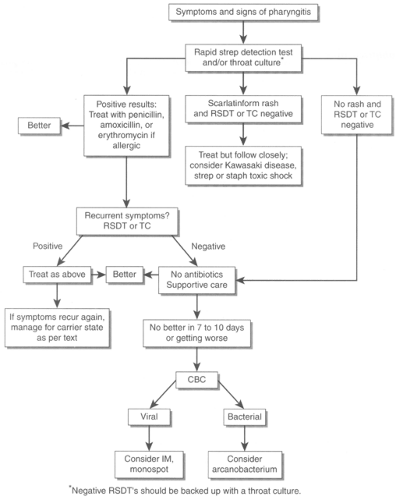

Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) is the most important of the bacterial etiologies, accounting for 8% to 40% of cases of acute pharyngitis in children and 5% to 9% of cases in teenagers (Pichichero, 1998). Other less prevalent primary bacterial etiologies include group C and G streptococcal species, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Arcanobacterium haemolyticus, and Mycoplasma and Chlamydia pneumoniae. In practical terms, all fall into the differential diagnosis of GABHS and are discussed in that section. An algorithm illustrating in general terms the clinical decision making for a child or adolescent with acute pharyngitis is presented in Figure 34-1.

ENTEROVIRAL PHARYNGITIS

The EV family consist of polio, echo, and Coxsachie viruses. Polio has been eradicated from much of the developed world through active immunization efforts beginning in the 1950s. The nonpolio EVs are frequent pathogens in children (Pichichero, 1998). They produce three very common clinical scenarios associated with acute pharyngitis: a nonspecific febrile illness characterized by myalgia and malaise, stomatitis classically known as herpangina, and the aptly termed hand, foot, and mouth (HFM) disease (Zaoutis & Klein, 1998). Herpangina means herpes-like pain and etiologically should not be confused with herpes simplex.

Other clinical manifestations of EV include aseptic meningitis, pleurodynia, myocarditis, pericarditis, meningoencephalitis, hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, and orchitis. EVs are responsible for a large proportion of infants admitted for sepsis workups during the summer (Rotbart, 1998). This section focuses on the clinical manifestations of EV associated with acute pharyngitis.

Pathology

The EVs are single-stranded RNA viruses belonging to the Picornaviridae family. The incubation period varies between 3 and 10 days. Upon entering the host though the gastrointestinal tract, initial viral replication occurs in the intestinal Peyer’s patches, leading to a minor viremia, with seeding of central nervous system (CNS), heart, liver, pancreas, skin, and mucous membranes. Parents often report that the child has some mild intestinal symptoms associated with the initial intestinal replication. Viral replication at these secondary sites accounts for a second or major viremia with further opportunity for CNS seeding. The two viremias described in this model help to explain the often biphasic symtomatology: fever for a day or two, followed by an afebrile period of 2 to 3 days, and finally an additional 2 to 5 days of fever. Neutralizing antibodies appear after about 6 to 12 days of symptoms, peak after 3 to 4 weeks, and result in resolution of symptoms (Zaoutis & Klein, 1998). For most EVs, the variety of clinical presentations results in symptoms lasting 7 to 10 days (Pichichero, 1998).

Epidemiology

In temperate climates, EV infections predominantly are seen in the warmer months. In tropical climates, they occur year-round. Transmission is primarily by the fecal-oral route and less commonly by respiratory droplet. Crowded living conditions, poor sanitation, and low socioeconomic class are all risk factors for infection. Risk factors for young children are day care attendance, poor hygiene, and lack of natural immunity (Zaoutis & Klein, 1998). A recent study emphasized that spread to family members of affected children is very common, occurring in 50% of siblings and 25% of parents (Pichichero, 1998).

History and Physical Examination

Clinicians should remember that up to 50% of EV infections may be asymptomatic. The remainder of the discussion focuses on clinical presentations associated with acute pharyngitis, namely the nonspecific febrile illness, herpangina, and HFM.

Enterovirus-Associated Nonspecific Febrile Illness

All EVs are associated with a nonspecific febrile illness. Typical manifestations include a rather sudden onset of fever

(which may be biphasic as described above), accompanied by muscle aches, headache, and mild intestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, mild diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Physical findings are not terribly specific but may include pharyngitis, cervical adenopathy, conjunctivitis, and a rash in 23% of patients (Rotbart, 1998; Zaoutis & Klein, 1998).

(which may be biphasic as described above), accompanied by muscle aches, headache, and mild intestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, mild diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Physical findings are not terribly specific but may include pharyngitis, cervical adenopathy, conjunctivitis, and a rash in 23% of patients (Rotbart, 1998; Zaoutis & Klein, 1998).

Herpangina

Findings include abrupt onset of fever associated with sore throat pain and difficulty swallowing. The fever may be extremely high, especially in younger patients. The classic enanthema begins a day later and consists of vesicles that ulcerate and are located posteriorly on the soft palate, tonsillar pillars, and posterior pharyngeal wall. In younger children, fluid intake may be severely compromised, which, along with increased insensible losses due to fever, contributes to the possibility of dehydration. Symptoms last for approximately 7 days.

A variant of herpangina consists of firm white nodules in the same distribution as the vesicles, termed lymphonodular pharyngitis. Herpangina is commonly associated with coxsackie A viruses but coxsackie B and echoviruses also have been implicated (Zaoutis & Klein, 1998).

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

Systemic symptoms of fever and dysphagia tend to be milder. The child may have a mild sore throat with or without fever, but the most frequent reason for presentation is the classic rash. The enanthema consists of scattered vesicles that ulcerate on the pharynx, buccal mucosa, and tongue. The ulcerations are much less painful than those seen in either herpangina or herpetic gingivostomatitis. The classic exanthem consists of vesicles on the palms, soles, and especially the periungual and interdigital surfaces. Nonvesicular lesions also may be seen on the buttocks and perineum (Rotbart, 1998; Zaoutis & Klein, 1998). Because of the milder constitutional symptoms, dehydration is almost never a concern. HFM is usually associated with coxsackie A 16, but other EVs also have been implicated.

Diagnostic Criteria and Studies

The diagnosis is established based on the clinical presentation and in the context of patterns of similar illness in other children, especially during warm weather. Although viral cultures are diagnostic, they are not practical or suitable for the primary care setting. PCR technology may soon become available; its cost and ease of use will determine how helpful it will become to primary care providers. For the foreseeable future, the diagnosis hinges on eliminating treatable forms of pharyngitis, namely GABHS pharyngitis, which can be simply and economically achieved with a throat culture or rapid streptococcal antigen test.

Providers should exclude the presence of GABHS pharyngitis by throat culture in patients with all but the most classic enteroviral presentation, such as HFM.

• Clinical Pearl

Establishing the presence of mild intestinal symptoms (initial site of viral replication) at the onset of symptoms is an important diagnostic clue for all EV infections but especially for EV-associated nonspecific febrile illness, in which classic enanthemas or exanthems are not apparent.

• Clinical Pearl

Herpangina produces high fevers, painful posterior intraoral vesicles, and the potential for dehydration. It can be distinguished clinically from HFM, which is a much milder illness, and from herpes simplex gingivostomatitis, in which the ulcers are classically anterior and predominantly gingival.

Management

Management of EV infections is supportive, consisting of hydration and antipyretics as needed to maintain the child’s level of comfort. Providers should pay particular attention to the young child with severe herpangina, because dehydration is not uncommon. They should instruct parents to offer frequent fluids. Parents should avoid giving carbonated or acidic juices and should favor blander beverages. The toddler with severe dysphagia may more readily accept cold drinks, pops, or ice cream. Education as to signs of dehydration and when to seek reevaluation is also important. Most EV infections will run a 7-day course, and providers should alert parents to this fact, thereby avoiding needless reevaluations, emergency room visits, and the potential for unnecessary antibiotics.

HERPES SIMPLEX GINGIVOSTOMATITIS

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) produces a wide variety of clinical diseases, including sexually transmitted genital infections; disease in the neonate and immunocompromised host, leading to encephalitis and systemic dissemination; gingivostomatitis; and the ubiquitous cold sore. This section focuses on the oral and pharyngeal manifestations of herpes simplex.

Pathology

The HSV is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the herpesvirus group that also contains Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus, and varicella-zoster virus. All members of the family share the distinct characteristic of becoming latent after primary infection and then reactivating periodically in response to various apparent (eg, infection, fatigue, stress, sunlight) or unknown triggers. Primary and recurrent infections can either be symptomatic or asymptomatic, and any combination of one can exist with another (Annunziato, 1998).

Pathologically, HSV produces skin vesicles and mucous membrane ulcers. Infected cells become multinucleated giant cells, and intranuclear inclusions become visible. During primary infection, the virus reaches nerve ganglia through sensory nerve endings in the infected skin. The virus can then remain latent within the nerve cells, only to reactivate later. The interplay between the host immune system and reactivation of HSV and the mechanism for reactivation remain unclear.

Symptomatic primary infections display vesicular eruptions and may show some systemic signs, such as fever. Symptomatic recurrent infections usually are characterized by cutaneous or mucous membrane eruptions but lack systemic findings. The incubation period varies between 2 days and 2 weeks.

• Clinical Pearl

The virus is so ubiquitous that after either a symptomatic or inapparent primary infection, 50% of the population is thought to harbor latent HSV (Annunziato, 1998).

Epidemiology

Herpetic infections have a worldwide distribution. The infection is transmitted from either primary or recurrent infections, either from symptomatic or asymptomatic individuals by direct contact with infected oral secretions or lesions (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 1997). Oral herpes also may be acquired through genital contact during oral sex. In lower socioeconomic groups, oral infection tends to occur at younger ages; in higher socioeconomic groups, it is mostly acquired in adolescence.

There are two antigenically distinct types: human HSV type I (HSV-1), primarily responsible for oral, eye, and CNS infections, and human HSV type II (HSV-II), primarily implicated in genital and neonatal infections. There are no strict distinctions, however, and both types can commonly cause infections at all sites.

History and Physical Examination

Herpetic gingivostomatitis is the clinical manifestation of a primary infection with HSV. The vast majority of children who are primarily infected have no distinguishable symptoms at all. The patients with symptomatic gingivostomatitis represent only about 5% of all those primarily infected (Annunziato, 1998).

As with herpangina due to enteroviral infection, the onset tends to be abrupt with high fever and poor oral intake. Physical examination reveals multiple small ulcers with a surrounding erythemetous base on the lips, gums, tongue, and inner cheeks, which may progress posteriorly to the soft palate and tonsils. Vesicles occasionally are seen on the perioral skin or the fingers of children who suck their thumbs.

The spectrum of severity varies, but children with severe disease may become dehydrated and require intravenous rehydration. In mild cases, the illness may last a week, but with severe disease, symptoms may persist for as long as 14 days (Annunziato, 1998). Recurrent herpes stomatitis presents as herpes labialis, more commonly referred to as a cold sore.

Diagnostic Criteria and Studies

Diagnosis is based on clinical grounds and the classic appearance of the intraoral lesions. Because early isolated posterior pharyngeal HSV lesions may be confused with those of GABHS, the provider should obtain a throat culture. Ultimately, the development of anterior ulcers will clarify the diagnosis.

• Clinical Pearl

HSV gingivostomatitis causes ulcers of the gums, lips, and tongue and less commonly lesions of the posterior pharynx. The presence of anteriorly located ulcers distinguishes HSV gingivostomatitis from enteroviral herpangina, which almost never causes anterior lesions.

Specimens for viral cultures may be obtained, with results usually available in a few days. They usually are not practical in the primary care setting. Providers may obtain faster results by newer enzyme immunoassay antigen techniques, but their applicability to the office setting remains to be demonstrated (AAP, 1997).

Management

Studies are lacking as to the use and efficacy of oral acyclovir in children with primary gingivostomatitis. Information inferred from the adult literature demonstrates that acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir all shorten the duration of symptoms and decrease viral shedding in cases of genital herpes. Valacyclovir and famciclovir offer no improved efficacy compared to acyclovir but do offer the advantage of less frequent dosing. No pediatric formulations, however, are available (AAP, 1997).

Given the above, its safety profile, and how well it is tolerated, providers should prescribe acyclovir at a dose of 80 mg/kg/d divided in five to six daily doses for all moderate and severe cases of HSV gingivostomatitis. To be effective, therapy should begin early (first 72 hours) in the course of illness. Topical acyclovir is not recommended.

Moderate to severe cases may benefit from the use of topical viscous xylocaine, swabbed on to the ulcers preprandially. This will allow a short window of time for the child to be able to eat but more importantly drink. Clinicians must caution parents not to overuse this topical anesthetic due to the dangers of systemic absorption.

Milder cases will require nothing more than supportive care consisting of hydration and antipyretics as needed to maintain the child’s level of comfort. As in the case of herpangina, providers should instruct parents to offer frequent fluids. Parents should avoid giving carbonated or acidic juices and favor blander beverages. The toddler with severe mouth pain may more readily accept cold drinks, pops, or ice cream. Education as to signs of dehydration and when to seek reevaluation is also important. As with any acute illness, providers should counsel parents as to the anticipated duration of the illness.

Because viral shedding in primary herpetic gingivistomatitis is considerable, parents should keep children away from day care or school until symptoms resolve. Children with common cold sores pose little risk and should go to daycare or school. Because HSV infection may be potentially life threatening to a neonate or other immunocompromised host, clinicians must caution caregivers not to expose their child with gingivostomatitis to others in these two vulnerable categories.

The treatment of the recurrent lesions of herpes labialis has not been adequately established in children. Topical acyclovir appears to have little efficacy, perhaps because by the time the lesions become apparent, it is too late to influence viral replication.

INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS

In children and particularly adolescents, infectious mononucleosis (IM) is an important consideration when the clinician is confronted with a patient with acute pharyngitis. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the cause of IM, yet clinically indistinguishable syndromes of fatigue, pharyngitis, and generalized lymphadenopathy may be seen with either acute cytomegalovirus infection or toxoplasmosis. All three may be termed “mono-like” illnesses.

The reader is referred to the excellent discussion of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of IM in chapter 30. This section focuses on the clinical presentation, diagnosis, differential considerations, and management of the patient with IM.

History and Physical Examination

Infectious mononucleosis may begin either abruptly with fever and a severe sore throat or less dramatically with

fatigue and malaise. For most primary care practitioners, it will present in the context of an acute pharyngitis.

fatigue and malaise. For most primary care practitioners, it will present in the context of an acute pharyngitis.

• Clinical Pearl

In general terms, younger children tend to have milder symptoms and signs. The older the patient, the more severe and dramatic is the symptomatology.

Clinical presentation of IM is the result of an immune system battle between EBV activated B lymphocytes seeking to proliferate and the host’s natural killer and T-cell response. Presumably, the older the patient, the more mature is his or her immune system, and hence the more “violent” the battle.

Sore throat is a cardinal symptom of IM, and tonsillar exudates are observed in 50% of cases. Palatal petechiae reminiscent of those with GABHS pharyngitis are common (Katz & Miller, 1998). Fevers and headaches of variable degree are commonly seen and may last up to 3 weeks. Lymphadenopathy is another characteristic symptom commonly seen in the cervical, axillary, epitrochlear, and inguinal regions.

Splenomegaly is seen in 50% of cases. Some controversy exists about whether the incidence is higher but clinically inapparent. Rupture of an enlarged spleen is a dreaded and life-threatening complication that usually follows trauma, although spontaneous ruptures have been reported (Rutkow, 1978).

Hepatomegaly may be seen in 10% to 40% of cases (Peter & Ray, 1998; Katz & Miller, 1998). Jaundice is rare. Abdominal pain is fairly common and may be due to a coexistent GABHS infection, stretching of the splenic capsule, hepatic tenderness, or mesenteric lymphadenopathy, which may be severe enough to mimic a surgical abdomen.

A polymorphic dermatitis appearing during the first few days of symptoms may be seen in anywhere from 5% to 19% of cases (Peter & Ray, 1998; Katz & Miller, 1998). It may be macular, papular, petechial, morbiliform, scarlatiniform, or even vesicular.

• Clinical Pearl

An itchy maculopapular eruption is seen in almost all patients with IM who are given ampicillin, amoxicillin, or related penicillins. The association is strong enough to be considered diagnostic and occurs 7 to 10 days after administration of these drugs (Peter & Ray, 1998; Katz & Miller, 1998). This rash is not an allergic reaction, and children can safely take these medications in the future.

Periorbital edema may be an early physical finding of IM; however, if mild, patient, parents, and clinician may overlook it. Less frequently, a clinical and x-ray picture are indistinguishable from atypical pneumonia can complicate IM. Rarely, infection is associated with signs of a bleeding diathesis due to thrombocytopenic purpura. Various neurologic manifestations, such as aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, acute cerebellar ataxia, and peripheral neuropathy, are also rare complicaitons (Katz & Miller, 1998).

Diagnostic Criteria and Studies

Given a teenager with a 2-week history of fatigue, sore throat, and swollen glands recently back from college or camp, the diagnosis becomes fairly obvious. In most cases, however, the provider will need to consider IM in the context of acute pharyngitis. Providers should obtain a throat culture or rapid strep antigen test for all patients, because 30% of patients with IM will also have “strep throat” (Peter & Ray, 1998).

• Clinical Pearl

Providers should consider IM in patients with pharyngitis who have negative throat culture or rapid strep antigen tests and whose symptoms do not resolve in 7 to 10 days, the expected course of most viral pharyngitides.

• Clinical Pearl

Because 30% of patients with IM are also positive for GABHS, providers also should suspect it in patients being treated for strep who do not show a rapid clinical response to therapy.

Providers should obtain a complete blood count (CBC) to both rule in the possibility of IM and help exclude the possibility of leukemia in a child with fever, generalized lymphadenopathy, and possibly hepatosplenomegaly. The CBC in IM will usually reveal an absolute lymphocytosis defined as a white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 5000 with more than 50% lymphocytes. The differential count will show atypical lymphocytes commonly greater than 10% (Peter & Ray, 1998). A normal hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelet count will help to distinguish IM from leukemia and other myeloinvasive diseases.

• Clinical Pearl

IM is one of the most common causes of anicteric or subclinical hepatitis in children and adolescents. Elevated liver enzymes are present in 70% to 90% of cases (Peter & Ray, 1998).

Clinically apparent jaundice is rare, occurring in less than 5% of cases; hyperbilirubinemia may be seen in 25% of cases (Katz & Miller, 1998).

Given a strong clinical suspicion for IM, the clinician should then consider obtaining confirmatory testing, which usually consists of a monospot slide test or an EBV antibody panel.

The utility, interpretation, and limitations of both tests is predicated on the child’s age, the duration of symptoms, and in the case of EBV titers, the high cost of the test itself.

The monospot slide test correlates well with the classic heterophile test, is available as a diagnostic kit with results ready in minutes, and is easily and inexpensively performed. Its sensitivity and specificity are respectively 85% and 97%, but only in older children and only by the second or third week of illness. The monospot may remain positive for up to 1 year following clinical resolution and as such, is not a good marker of active disease.

Children younger than 4 years commonly do not develop a heterophile antibody to EBV infection, and in this age group, the monospot’s sensitivity is less than 20% (Peter & Ray, 1998). Early in the illness, the test is also not useful, becoming positive in 80% of patients only by the third week of illness (Katz & Miller, 1998).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree