Monitors

Alexander C. Gerhart

Twenty-first century anesthesia providers are increasingly being asked to provide anesthesia care in office-based environments. Under ideal circumstances, the cases involve healthy American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class 1 patients undergoing minor surgical procedures with low potential for complication. Although risk can be minimized through proper patient selection, adequate training, and vigilance, it cannot be eliminated. The use of proper patient monitors coupled with the experience of a trained anesthesia provider can detect potential adverse events, prevent complications, and minimize morbidity. The ASA mandates that all anesthetics, whether general, regional, or monitored anesthesia care (MAC) be provided under The Standards for Anesthetic Monitoring (http://www.asahq.org/publicationsAndServices/standards/02.pdf) (see Appendix 4). Standard I states that adequately trained personnel provide the anesthetic. Standard II states that for all anesthetics, the patient’s oxygenation, circulation, ventilation, and temperature shall be continually monitored (see Box 10.1). The next few pages will describe the current monitoring devices available, as well as look toward the future of monitoring techniques as they pertain to office-based anesthesia.

Box 10.1 • ASA-Mandated Monitoring

Oxygenation

Circulation

Ventilation

Temperature

OXYGENATION

During every administration of general anesthesia using an anesthesia machine, the concentration of oxygen in the breathing system shall be measured by an oxygen analyzer with a low oxygen concentration limit alarm in use (see Box 10.2).

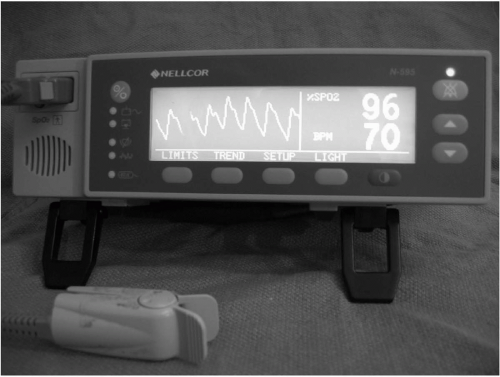

During all anesthetics, a quantitative method of assessing oxygenation such as pulse oximetry shall be employed (see Figure 10.1).

Box 10.2

Concentration of Inspired oxygen is measured with oxygen analyzer.

Oxygenation is measured by pulse oximetry.

There are several types of oxygen analyzers in commercial use on modern anesthesia machines. The most common is the galvanic cell, which is composed of a lead anode and a gold cathode bathed in potassium chloride. The lead anode is consumed by hydroxyl ions formed at the gold cathode forming lead oxide and producing a current. This current can be measured and the inspired oxygen content calculated based on the current generated. The lead anode of galvanic (fuel) cells is constantly being degraded, and fuel cell life can be prolonged by exposing them to room air when not in use. Other less common techniques for measuring inspired oxygen content include paramagnetic analysis and polarographic electrodes.

The use of pulse oximetry is mandatory for all patients undergoing an anesthetic. There are no contraindications to its use. Pulse oximetry is based on a sensor containing either two or three light sources (light emitting diodes), and one light detector (photodiode). Hemoglobin saturation is calculated based on the knowledge that oxyhemoglobin (960 nm) and deoxyhemoglobin (660 nm) absorb light at different wavelengths. The ratio of light absorbed at each wavelength provides the measure of hemoglobin saturation. Many factors may confound pulse oximeter readings (see Box 10.3). Carboxyhemoglobin, which occurs in the setting of carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning, absorbs light at the same wavelength as oxyhemoglobin and therefore yields artificially elevated readings. Methemoglobinemia absorbs light at both 660 and 990 nm, and yields a pulse oximeter reading of 85%. Other common causes of spurious pulse oximeter readings include ambient light interference, decreased perfusion, decreased cardiac output, increased systemic vascular resistance, peripheral vascular disease, and motion artifact. Patients will often present for office-based anesthetics with nail polish or artificial nails, which may affect the quality of pulse oximetry tracings. Nail polish is easily removed with acetone or the oximeter may be placed on a toe, or an ear. Another option would be to use a disposable oximeter sensor that can be placed on the nose or forehead.

Box 10.3

Common Causes of Abnormal Pulse Oximetry Values

Carboxyhemoglobin

Methemoglobin

Ambient light interference

Decreased perfusion (increased systemic vascular resistance, decreased CO, peripheral vascular disease)

Motion artifact

Artificial fingernail applications

Nail polish

The use of pulse oximetry and oxygen analyzers cannot be disputed, but they must be considered the starting point for the monitoring of oxygenation. The anesthesia provider must also note subjective cues of inadequate oxygenation in the awake patient, including change in mentation and dyspnea (see Box 10.4). Additionally, adequate lighting and exposure of the patient are required to allow inspection and assessment of color and skin tone. In the discussion on monitoring oxygenation, it is worthwhile to mention the need to ensure the adequacy of the primary oxygen supply and the presence of a reserve oxygen supply. The importance of ensuring an adequate oxygen supply cannot be overstated. There have been several reported fatalities occurring during the administration of anesthesia in office-based settings in which patients died of respiratory failure in locations without supplemental oxygen available.

Box 10.4

Subjective Assessment of Oxygenation

Change in mentation

Complaints of dyspnea

Pallor

Cyanosis

VENTILATION

Every patient receiving general anesthesia shall have the adequacy of ventilation continually evaluated (see Box 10.5).

When a tracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway is inserted, correct position must be verified by the presence of end-tidal CO2. The continued presence of end-tidal CO2 will be quantitatively measured from the time of endotracheal tube/laryngeal mask airway insertion, until its removal, or transfer of the patient to a postoperative location.

When ventilation is controlled by a mechanical ventilator, there shall be in continuous use a device capable of detecting disconnection of components of the breathing system.

During regional anesthesia and MAC, the adequacy of ventilation shall be evaluated, at least, by continual observation of qualitative clinical signs.

Box 10.5

Assessment of Adequate Ventilation

End-tidal CO2 monitor

Capnography tracing

Disconnect alarm for circuit

Physical examination and observation of chest wall movement

Presence of condensation on a face mask or inside an endotracheal tube

Auscultation of breath sounds (precordial stethoscope)

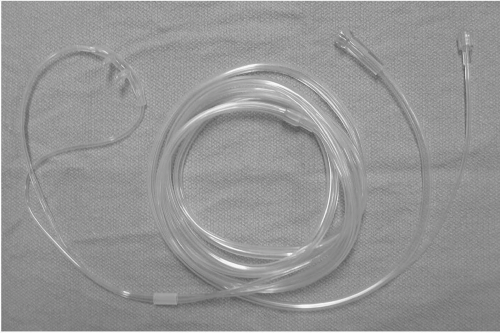

The simplest techniques for monitoring ventilation include inspection, auscultation, and palpation. For regional anesthesia or MAC, monitoring ventilation may simply include listening to the respiratory pattern and rate and observation of chest excursion. The addition of a capnography sampling line to a nasal cannula or face mask provides qualitative indications of respiratory rate and effectiveness in wave form. A precordial stethoscope may also be employed although awake patients may complain of its weight, and many anesthesia providers object to being physically tethered to a patient.

For a patient undergoing a general anesthetic, it is imperative that endtidal CO2 is continuously monitored and it is strongly encouraged that the

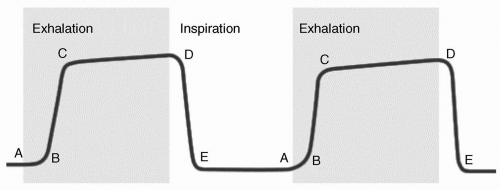

anesthesia provider has access to capnography tracings. Capnography tracings and end-tidal CO2 monitoring provide clues to many pertinent clinical conditions (see Figures 10.2 and 10.3 and Box 10.6). Esophageal intubation, circuit disconnect, failure of inspiratory or expiratory vales, exhaustion of CO2 absorbent, obstruction of the endotracheal tube, obstructive pulmonary disease, restrictive pulmonary disease, spontaneous diaphragm movement, pulmonary embolism, and malignant hyperthermia may all result in changes in the capnograph tracing. For patients undergoing procedures on the face, where oxygen cannula or mask may be contraindicated, transcutaneous CO2 monitors are available.

anesthesia provider has access to capnography tracings. Capnography tracings and end-tidal CO2 monitoring provide clues to many pertinent clinical conditions (see Figures 10.2 and 10.3 and Box 10.6). Esophageal intubation, circuit disconnect, failure of inspiratory or expiratory vales, exhaustion of CO2 absorbent, obstruction of the endotracheal tube, obstructive pulmonary disease, restrictive pulmonary disease, spontaneous diaphragm movement, pulmonary embolism, and malignant hyperthermia may all result in changes in the capnograph tracing. For patients undergoing procedures on the face, where oxygen cannula or mask may be contraindicated, transcutaneous CO2 monitors are available.

Box 10.6

Diagnostic Clues Provided by Capnography

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree