Chapter 7 Modalities working with massage

In this chapter a number of modalities that integrate well with massage therapy will be discussed. To support proficiency, practical examples and skill enhancement exercises are included. The methods presented include:

• positional release technique

• integrated neuromuscular inhibition (for trigger point deactivation)

CONNECTIVE TISSUE FOCUS

The fascia is subject to trauma through overstretching or impact, and scar tissue and adhesions can form. The main problem, however, comes from chronic changes as a result of long-term stress. The fascia thickens and becomes more fibrous, which makes it less mobile and reduces its permeability. This affects the function of the underlying muscle and may restrict its free movement. In addition, if the interstitial fluid cannot pass freely through the fascia, the muscle may not get an adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients, and will be less able to eliminate metabolic waste material.

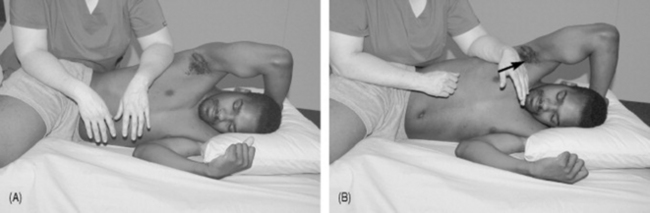

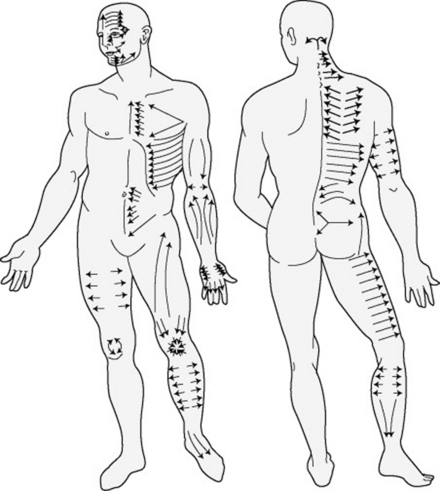

Massage is able to stretch specific localized areas of tissue in a way that may not be possible with other approaches. Longitudinal (tension force) stroking and kneading (bend and torsion force) can stretch the tissues by drawing them apart and in all possible directions (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Application of connective tissue massage, modified from Bindegewebmassage. This system primarily introduced the mechanical forces of tension, bend, shear, and torsion.

Tissue movement methods

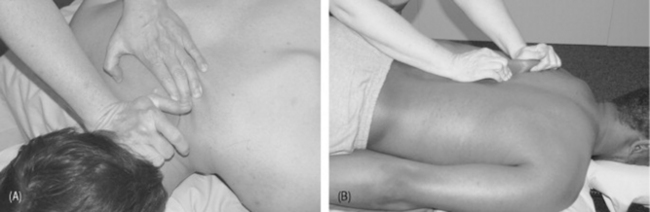

The more subtle connective tissue approaches rely on the skilled development of following tissue movements. The process is as follows (Figure 7.2):

1. Make firm but gentle contact with the skin. This is best accomplished with the tissue in the ease position.

2. Increase the downward, or vertical, pressure slowly until resistance is felt; this barrier is soft and subtle.

3. Maintain the downward pressure at this point; now add horizontal drag until the resistance barrier is felt again.

4. Sustain the horizontal pressure and wait.

5. The tissue will seem to creep, unravel, melt, slide, quiver, twist, or dip, or some other movement sensation will be apparent.

6. Follow the movement, gently maintaining the tension on the tissues, encouraging the pattern as it undulates though various levels of release.

7. Slowly and gently release first the horizontal force and then the vertical force.

Twist-and-release kneading and compression applied in the direction of the restriction can also release these fascial barriers (Figure 7.3).

A good grip with the skin is essential, so there must be no lotion or oil present. This grip can be with the hands or forearms. The technique is even sometimes performed with a towel to provide stronger contact with the skin.

NEUROMUSCULAR TECHNIQUE

Neuromuscular technique (NMT) evolved in Europe in the 1930s as a blend of traditional Ayurvedic (Indian) massage techniques and soft tissue methods derived from other sources. Stanley Lief DC and his cousin Boris Chaitow ND DO developed the techniques now known as NMT into an excellent and economical diagnostic (and therapeutic) tool (Chaitow 2003a, Youngs 1962).

There is also an American version of NMT that emerged from the work of chiropractor Raymond Nimmo (Cohen & Gibbons 1998). NMT is an effective method to address trigger point activity.

Basics of NMT

Neuromuscular thumb technique

The therapist uses the medial tip (ideally) of the thumb to sequentially ‘meet and match’ tissue density/tension and to insinuate the digit through the tissues, seeking local dysfunction (Figure 7.4).

Application of NMT

Diagnostic assessment involves one superficial and one moderately deep contact only.

TRIGGER POINT METHODS

Theories of trigger point development are outlined in Box 7.1.

Box 7.1 Theories of trigger point development

1 ENERGY CRISIS THEORY

This is the earliest explanation of trigger point formation (Bengtsson et al 1986, Hong 1996, Simons et al 1999).

Waste products of metabolism accumulate (Simons et al 1999), and this causes some of the pain because of irritation and sensitization of sensory nerves (nociceptors).

This concept was partly supported by Bengtsson et al (1986).

2 THE MOTOR ENDPLATE THEORY

The motor nerve connects with a muscle cell at the motor endplate.

Research has shown that each trigger point contains very small areas (loci) that produce unusual electrical activity (Hubbard & Berkhoff 1993). These loci are usually found at the motor endplate zone (Simons 2001, Simons et al 2002).

The activity seen on EMG (electromyogram) is thought to be the result of an increased rate of release of acetylcholine (ACh) from the nerve cell. This may be enough to cause activation of a few contractile elements and be responsible for some degree of muscle shortening (Simons 1996).

3 RADICULOPATHIC MODEL

Some researchers have a different model altogether. They think that there is a neurologic cause, and that trigger points are a secondary phenomenon (Gunn 1997, Quintner & Cohen 1994).

Gunn (1997) suggests that myofascial pain often derives from intervertebral disk degeneration, which causes nerve root compression and paraspinal muscle spasm. This is described as a form of neuropathy (carpal tunnel syndrome is a neuropathy) that sensitizes and irritates structures in the distribution of the nerve root, and causes distal muscle spasm.

Active and latent trigger points

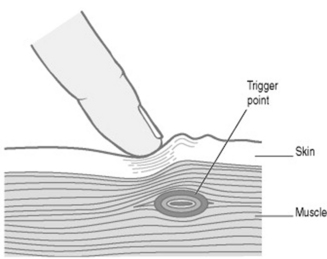

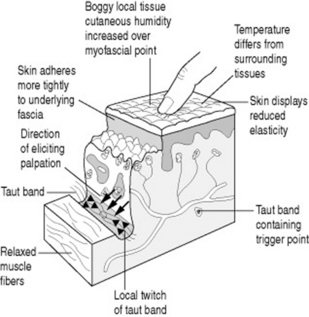

The pain characteristics of an active myofascial trigger point (Figure 7.6) are as follows:

• When pressure is applied, active trigger points are painful and either refer (i.e., symptoms are felt at a distance from the point of pressure) or radiate (i.e., symptoms spread from the point of pressure).

• Symptoms that are referred or radiated include pain, tingling, numbness, burning, itching or other sensations and, most importantly, in an active trigger these symptoms are recognizable (familiar) to the person.

• Other signs of an active trigger point include the ‘jump sign’, palpable indications such as a taut band, fasciculation, etc.

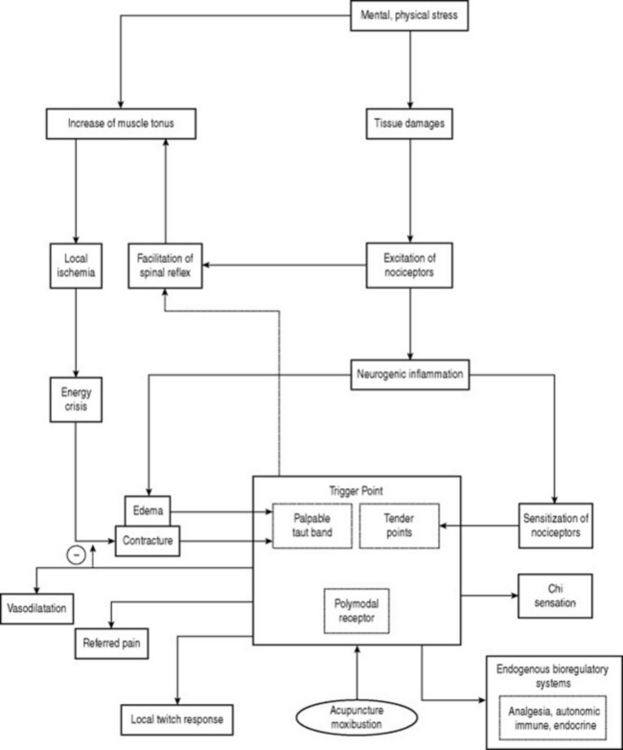

Figure 7.5 Polymodal receptor hypothesis of acupuncture and moxibustion.

(Adapted from Kawakita et al 2002.)

The pain characteristics of a latent myofascial trigger point are as follows:

• Commonly the individual is not aware of the existence of a latent point until it is pressed (i.e., unlike an active point, a latent one seldom produces spontaneous pain).

• When pressure is applied to a latent point it is usually painful, and it may refer (i.e., symptoms are felt at a distance from the point of pressure) or radiate (i.e., symptoms spread from the point of pressure).

• If the symptoms – whether pain, tingling, numbness, burning, itching or other sensations – are not familiar, or perhaps are sensations that the person used to have in the past but has not experienced recently, then this is a latent myofascial trigger point (Figure 7.7).

Neck, head and face referral patterns and major trigger point locations are illustrated in Box 7.2; key and satellite trigger points are outlined in Box 7.3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree