CHAPTER 8 METABOLIC AND ENDOCRINE PROBLEMS

SODIUM

(Normal range serum sodium 135–145 mmol/L.)

Hyponatraemia

The causes of hyponatraemia are shown in Table 8.1.

TABLE 8.1 Causes of hyponatraemia

| Excess water intake | Hypotonic fluids TURP syndrome Water intoxication |

| Reduced free water clearance | Stress response with raised ADH Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion Renal impairment Cardiac failure |

| Loss of body sodium | GI tract losses Renal losses including diuretic therapy Adrenal insufficiency Hyperpyrexia and sweating (inadequate salt replacement) |

Hyponatraemia is most commonly due to an excess of extracellular fluid (rather than sodium loss). This is often the result of excessive use of hypotonic intravenous fluids. Hyponatraemia may also result from the chronic use of some diuretic drugs; this is more commonly seen in the elderly. More rarely, hyponatraemia is associated with other forms of organ dysfunction, including renal dysfunction and hepatic cirrhosis (where it is seen in association with secondary hyperaldosteronism). Treatment is not usually necessary unless the serum sodium falls below 130 mmol/L. Serum sodium below 120 mmol/L may be associated with altered conscious level and fits. Symptoms are related as much to the speed of change in concentration as to the actual measured level.

Hypernatraemia

Give additional free water as 5% dextrose (e.g. 1 L over 6–12 h) or water via NG tube. Consider diluting enteral feeds with sterile water.

Give additional free water as 5% dextrose (e.g. 1 L over 6–12 h) or water via NG tube. Consider diluting enteral feeds with sterile water. If additional fluid is contraindicated or undesirable, consider renal replacement therapy. This should be discussed with the nephrologists, on a case-by-case basis.

If additional fluid is contraindicated or undesirable, consider renal replacement therapy. This should be discussed with the nephrologists, on a case-by-case basis.POTASSIUM

(Normal range serum potassium 3.5–5 mmol/L.)

Potassium is primarily an intracellular ion. Small changes in serum concentration have significant effects on nerve conduction and muscle contraction.

Hypokalaemia

Causes of hypokalaemia are shown in Box 8.1.

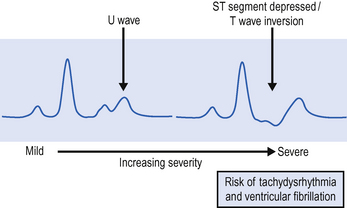

Hypokalaemia is relatively common in the ICU. ECG changes include ST depression, flattening of the T wave and prominent U wave. If severe (<2 mmol/L), cardiac arrhythmias, including supraventricular and ventricular extrasystoles, tachycardias, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular fibrillation, may occur (Fig. 8.1).

If additional potassium is required:

Give 20 mmol of K+ in 20–40 mL of saline over 1 h via a central venous catheter using an infusion pump. Repeat as necessary.

Give 20 mmol of K+ in 20–40 mL of saline over 1 h via a central venous catheter using an infusion pump. Repeat as necessary.Hyperkalaemia

Causes of hyperkalaemia are shown in Box 8.2.

Box 8.2 Causes of hyperkalaemia

Spurious (e.g. haemolysed blood sample, check result)

Iatrogenic (excess administration)

Muscle injury (including suxamethonium, crush injury, compartment syndrome)

Tumour lysis syndrome (following chemotherapy)

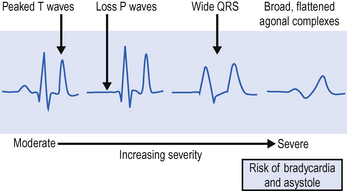

ECG changes include peaked T waves, broad QRS complexes and conduction defects (Fig. 8.2). Asystole may occur. Urgent treatment is usually required, although patients with long-term end-stage renal failure may be more tolerant of hyperkalaemia than the general intensive care patient population.

CALCIUM

(Normal range standard serum calcium 2.12–2.62 mmol/L.)

(Normal range ionized serum calcium 0.84–1 mmol/L.)

Most laboratories measure total calcium, which includes bound and unbound fractions. The unbound fraction (ionized Ca2+), which is the physiologically active component, varies with the albumin concentration. Therefore, look at the corrected figure, which takes account of protein binding. Alternatively, many blood gas analysers now measure ionized Ca2+ directly.

Hypocalcaemia

Hypocalcaemia is common on the ICU. Typical causes are shown in Box 8.3.

Box 8.3 Causes of hypocalcaemia

Citrate accumulation (massive transfusion / liver failure)

Generalized failure of Ca2+ homeostasis in severe sepsis

Secondary to phosphate accumulation in renal failure

Hypercalcaemia

This occurs less commonly, and is generally due to an underlying disease process. Typical causes are listed in Box 8.4.

Give 0.9% saline to rehydrate the patient. Check plasma osmolality is within the normal range (280–290 mosmol/L).

Give 0.9% saline to rehydrate the patient. Check plasma osmolality is within the normal range (280–290 mosmol/L). A forced diuresis may be used to aid excretion. Furosemide (frusemide) is administered and the urine output replaced with alternating 0.9% saline and 5% dextrose.

A forced diuresis may be used to aid excretion. Furosemide (frusemide) is administered and the urine output replaced with alternating 0.9% saline and 5% dextrose. Calcitonin reduces the rate of calcium and phosphate release from the bones. It is useful in patients with hypercalcaemia associated with malignancy, and generally reduces the calcium level within 2 h.

Calcitonin reduces the rate of calcium and phosphate release from the bones. It is useful in patients with hypercalcaemia associated with malignancy, and generally reduces the calcium level within 2 h. Bisphosphonates (e.g. disodium etidronate) also reduce release of calcium from bones but generally take a few days to achieve maximum effect.

Bisphosphonates (e.g. disodium etidronate) also reduce release of calcium from bones but generally take a few days to achieve maximum effect.PHOSPHATE

(Normal range serum phosphate 0.7–1.25 mmol/L.)

Hyperphosphataemia

Hyperphosphataemia is caused by excessive intake or decreased excretion (e.g. renal failure). Maintain adequate hydration with 5% dextrose. If severe, consider the need for renal replacement therapy. Phosphate is effectively removed by continuous RRT techniques, with haemodialysis and haemodiafiltration performing better than simple filtration techniques.

MAGNESIUM

(Normal range serum magnesium 0.7–1 mmol/L.)

Rapid correction of severe hyponatraemia can cause central pontine demyelination (brainstem damage) and death. It is recommended that sodium should not rise more than 2 mmol / L per hour and by not more than 12 mmol / L in 24 h, to achieve an initial plasma sodium level of 120–130 mmol / L. The use of hypertonic saline solutions is controversial. Seek advice.

Rapid correction of severe hyponatraemia can cause central pontine demyelination (brainstem damage) and death. It is recommended that sodium should not rise more than 2 mmol / L per hour and by not more than 12 mmol / L in 24 h, to achieve an initial plasma sodium level of 120–130 mmol / L. The use of hypertonic saline solutions is controversial. Seek advice.

Rapid correction of hypernatraemia, particularly if serum sodium is >160 mmol / L, can result in cerebral oedema as water enters the brain. As with hyponatraemia, correct slowly over 24–48 h.

Rapid correction of hypernatraemia, particularly if serum sodium is >160 mmol / L, can result in cerebral oedema as water enters the brain. As with hyponatraemia, correct slowly over 24–48 h.

Inadvertent and inappropriate injection of strong potassium solutions has been associated with death. These solutions should be treated as a controlled drug, and use should be governed by local protocols. Ideally, strong potassium infusions should be prepared by a pharmacy aseptic service. If you are required to prepare potassium infusions, ensure that fluids are thoroughly mixed before administration. Strong potassium chloride solution has a higher specific gravity than standard i.v. solutions and can ‘layer’ at the bottom of a bag / syringe. Administration should be via a central venous cannula to avoid the risk of extravasation injury. During infusion continuous ECG monitoring and regular blood sampling are mandatory.

Inadvertent and inappropriate injection of strong potassium solutions has been associated with death. These solutions should be treated as a controlled drug, and use should be governed by local protocols. Ideally, strong potassium infusions should be prepared by a pharmacy aseptic service. If you are required to prepare potassium infusions, ensure that fluids are thoroughly mixed before administration. Strong potassium chloride solution has a higher specific gravity than standard i.v. solutions and can ‘layer’ at the bottom of a bag / syringe. Administration should be via a central venous cannula to avoid the risk of extravasation injury. During infusion continuous ECG monitoring and regular blood sampling are mandatory.