INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses the diagnosis and differentiation of delirium and dementia in the elderly and provides an overview of selected common mental health disorders in the aging population.

The proportion of ED visits by older adults continues to increase with the exponential growth of the geriatric population.1 Delirium, dementia, and depression can affect older adults, and the disorders are often interrelated. It can be difficult to identify delirium in patients with dementia, particularly because individuals with dementia are more likely to develop delirium.2 Patients who develop delirium are more likely to develop dementia later in life.3,4,5,6 Distinguishing between dementia and delirium is an important aspect of caring for older patients.

It can also be difficult to diagnose depression in patients with dementia given that both can present with similar symptoms such as apathy.7 Also, depression in late life has been associated with increased risk of developing dementia, further demonstrating that dementia, delirium, and depression are interconnected, increase the risk of each other, and are all associated with increased risk of mortality and morbidity.8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Table 288-1 provides distinguishing features of delirium, dementia, and psychiatric disorders. Chapters 168, “Altered Mental Status and Coma,” and 286, “Mental Health Disorders: ED Evaluation and Disposition,” also discuss the distinctions between delirium, dementia, and psychiatric disorders.

| Characteristic | Delirium | Dementia | Psychiatric Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Over days | Insidious | Varies |

| Course over 24 h | Fluctuating | Stable | Varies |

| Consciousness | Reduced or hyperalert | Alert | Alert or distracted |

| Attention | Disordered | Normal | May be disordered |

| Cognition | Disordered | Impaired | Rarely impaired |

| Orientation | Impaired | Often impaired | May be impaired |

| Hallucinations | Visual and/or auditory | Often absent | May be present |

| Delusions | Transient, poorly organized | Usually absent | Sustained |

| Movements | Asterixis, tremor may be present | Often absent | Varies |

DELIRIUM

Delirium is an acute change in cognition that fluctuates rapidly over time and is often reversible.15 Delirium is frequently the first sign of underlying acute medical illness. Patients demonstrate altered levels of consciousness, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered perception.15 There are three main types of delirium: hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed.16 By far, the most common types are hypoactive and mixed delirium, which also have the highest potential to be missed.17,18,19,20,21,22,23 Hypoactive delirium has been called “quiet delirium” because patients have decreased psychomotor activity and can appear somnolent. If hypoactive delirium is confused for depression, the underlying medical disorder causing the delirium can be missed.24,25,26 Hyperactive delirium, in contrast, is characterized by increased psychomotor activity, and patients are often agitated, anxious, and sometimes combative. Mixed type can present with a combination of both hyperactive and hypoactive states that fluctuate over time.

Delirium is thought to be present in 7% to 10% of older patients presenting to the ED.17,27,28 Environmental risk factors for delirium include functional dependence, living in a nursing home, and hearing impairment.17,29 Delirium is an independent marker for mortality and is associated with a longer length of hospital stay than the median, increased hospital complications, discharge to long-term care facilities, and lasting cognitive deficits.30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37 Even though delirium is a common disorder in the elderly, the diagnosis is missed by providers in 57% to 83% of cases.27,38,39,40,41 If delirium is missed in the ED, it is likely to be missed on the inpatient services as well.17

The differential diagnosis of delirium includes dementia, depression, or another underlying psychiatric disorder. Such conditions can also be comorbidities of each other. However, first assess for delirium and then consider the possibility of the other disorders.

Focus history taking on identifying the patient’s baseline mental status and level of functioning and the time course of changes. Ask about past medical history and recent illness. Obtain an accurate medication list, and ask about over-the-counter medications, medications with anticholinergic properties, or any new medications.42 Ask about substance abuse to assess the likelihood of intoxication or withdrawal. Any past psychiatric history requires close investigation of prior diagnoses, hospitalizations, and medications. Determine the patient’s ability to make informed medical decisions, and determine whether another individual has legal power of attorney for medical decision making.

When attempting to differentiate delirium from dementia, consider several key factors. An acute change in mental status is more consistent with delirium than with dementia, and a fluctuating course over time is also more likely due to delirium.43 Altered level of consciousness, inattention, and disorganized thinking are all more common in delirium than in dementia.43

The physical examination should be thorough. Vital signs must be complete, to include oxygen saturation and temperature. Determine the blood glucose level. Baseline blood pressures may be higher than in younger age groups, and tachycardia can be masked by pharmacologic and/or physiologic limitations. Older patients have lower basal temperatures, with means of 97.3 to 97.8°F depending on the time of the day, so the threshold for a fever is lower than the assumed “normal” of 98.6°F.44 Look for evidence of trauma, as patients may not recall falling or injuring themselves. Examine the entire body, making sure to look at the patient’s back and heels for evidence of decubitus ulcers. Perform a complete neurologic exam, checking for focal findings, abnormal posturing, or difficulty with gait, coordination, or vision. A normal physical examination does not exclude the diagnosis of delirium.

Mental status examination is performed to identify delirium and differentiate it from other conditions.27,35,38,39,40,41,45,46 The examination consists of an assessment of six mental-behavioral components (Table 288-2).

Appearance, behavior, and attitude Is dress appropriate? Is motor behavior at rest appropriate? Is the speech pattern normal? Disorders of thought Are the thoughts logical and realistic? Are false beliefs or delusions present? Are suicidal or homicidal thoughts present? Disorders of perception Are hallucinations present? Mood and affect What is the prevailing mood? Is the emotional content appropriate for the setting? Insight and judgment Does the patient understand the circumstances surrounding the visit? Sensorium and intelligence Is the level of consciousness normal? Is cognition or intellectual functioning impaired? |

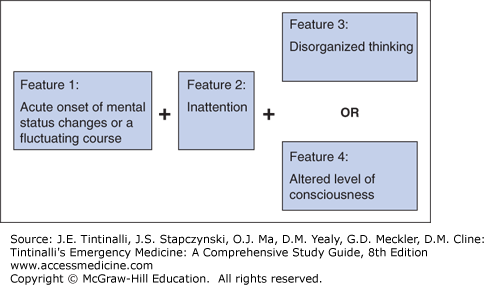

Two of the most common screening tests used to detect delirium are the Confusion Assessment Method for general use and the Confusion Assessment Method–Intensive Care Unit for intubated patients who are not heavily sedated.47,48 Figure 288-1 demonstrates the components of the Confusion Assessment Method. Inattention is characterized by an easily distracted patient who has difficulty keeping track of the conversation. Disorganized thought processes are rambling, unclear, or illogical. An altered level of consciousness is lethargy, lack of responsiveness, or coma—essentially anything other than alert. The diagnosis of delirium requires features 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4. See Table 288-3 for further details about using the Confusion Assessment Method and the Confusion Assessment Method–Intensive Care Unit.47,48

| Confusion Assessment Method | Confusion Assessment Method–Intensive Care Unit Version | |

|---|---|---|

| Feature 1. Acute Onset and Fluctuating Course | Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? Did the (abnormal) behavior fluctuate during the day, that is, tend to come and go, or increase or decrease in severity? Sources: Family or nurse | Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the baseline? Did the (abnormal) behavior fluctuate during the past 24 h, that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity? Sources of information: Serial Glasgow Coma Scale or sedation score ratings over 24 h, as well as readily available input from the patient’s bedside critical care nurse or family |

| Feature 2. Inattention | Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention, for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said? | Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention? Is there a reduced ability to maintain and shift attention? Sources of information: Attention screening examinations by using either picture recognition or Vigilance A random letter test. Neither of these tests requires verbal response, and thus they are ideally suited for mechanically ventilated patients. |

| Feature 3. Disorganized Thinking | Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable switching from subject to subject? | Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable switching from subject to subject? Was the patient able to follow questions and commands throughout the assessment? “Are you having any unclear thinking?” “Hold up this many fingers.” (examiner holds two fingers in front of the patient) “Now, do the same thing with the other hand.” (not repeating the number of fingers) |

| Feature 4. Altered Level of Consciousness | Is the patient’s mental status anything other than alert, for example, vigilant, lethargic, stuporous, or comatose? | Any level of consciousness other than “alert.” Alert—normal, spontaneously fully aware of environment and interacts appropriately Vigilant—hyperalert Lethargic—drowsy but easily aroused, unaware of some elements in the environment, or not spontaneously interacting appropriately with the interviewer; becomes fully aware and appropriately interactive when prodded minimally Stupor—difficult to arouse, unaware of some or all elements in the environment, or not spontaneously interacting with the interviewer; becomes incompletely aware and inappropriately interactive when prodded strongly Coma—unarousable, unaware of all elements in the environment, with no spontaneous interaction or awareness of the interviewer, so that the interview is difficult or impossible even with maximal prodding |

Laboratory testing and imaging are obtained to identify the treaTable causes of delirium (Tables 288-3 and 288-4).46

| Drugs | Any new additions, increased dosages, or interactions Consider over-the-counter drugs and alcohol Consider high-risk drugs* |

| Electrolyte disturbances | Dehydration, sodium imbalance, thyroid abnormalities |

| Lack of drugs | Withdrawals from chronically used sedatives, including alcohol and sleeping pills Poorly controlled pain (lack of analgesia) |

| Infection | Especially urinary and respiratory tract infections |

| Reduced sensory input | Poor vision, poor hearing |

| Intracranial | Infection, hemorrhage, stroke, tumor Rare; consider only if new focal neurologic findings, suggestive history, or diagnostic evaluation otherwise negative |

| Urinary, fecal | Urinary retention: “cystocerebral syndrome” Fecal impaction |

| Myocardial, pulmonary | Myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, exacerbation of heart failure, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypoxia |

In geriatric patients, infections, such as urinary tract infections and pneumonia, are associated with nearly half of cases of delirium,49 and medications may account for another 40%.50,51,52

Laboratory Testing Check point-of-care glucose as soon as possible after patient arrival in the ED. Obtain CBC and basic metabolic studies, including calcium, phosphorus, and hepatic enzymes. Urinalysis is necessary because urinary tract infections are a frequent cause of delirium. Obtain cardiac markers. Consider an arterial blood gas analysis, especially in patients with chronic lung disease, because hypercarbia can cause delirium.42 Obtain thyroid function studies.53 Urine or serum toxicologic studies may be in order. Lumbar puncture may be necessary (after CT scan) if there is suspicion for meningitis or encephalitis or if the patient has had a new-onset seizure.43 Further studies may be needed depending on the results of history, examination, and basic tests.

Imaging/Ancillary Tests Electrocardiogram and chest radiograph are essential.54 Head CT scan is advised for patients with signs of, or a history of, trauma, focal neurologic deficits, impaired level of consciousness, or an otherwise unrevealing evaluation.55,56

Direct treatment to the underlying cause of delirium. Withhold or remove medications that are responsible for delirium. Treat infection, provide IV fluids for dehydration, correct hypoglycemia, and treat pain. Select doses of analgesics and narcotics for each individual patient and monitor for adverse effects.

Provide the patient with his/her glasses or hearing aids, allow family or caregivers at the bedside, provide frequent reorientation about surroundings and course of care, and make sure there is access to a bathroom.57 The Multicomponent Intervention to Prevent Delirium in Hospitalized Older Patients identified six risk factors (cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual impairment, hearing impairment, and dehydration) for the development of delirium and targeted each risk factor with specific interventions carried out by a multidisciplinary team.57 Precipitating factors in the development of delirium in the hospital include the use of physical restraints, malnutrition, use of a bladder catheter, more than three medications added, and any iatrogenic event.58 Preventing and minimizing these factors are especially important when long ED stays are unavoidable.

If the patient is agitated, begin with a nonpharmacologic approach by addressing patient needs (such as using the restroom and, if possible, allowing the patient to eat or drink), providing comforTable surroundings, and having the family close by.57,59 Avoid bladder catheters. Physical restraints should be an absolute last resort. If basic interventions are not successful, consider medication (Figure 288-2). We recommend the avoidance of benzodiazepines in the elderly if at all possible, unless alcohol withdrawal is the cause of delirium.60 Benzodiazepines can cause paradoxical disinhibition and increased agitation in the elderly. If a benzodiazepine is used, consider a short-acting, glucuronidated agent such as lorazepam, oxazepam, or temazepam to minimize prolonged benzodiazepine effects. Avoid antihistamines, because this drug class has strong anticholinergic effects and can induce or worsen delirium in the elderly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree