Key Clinical Questions

Is the classic triad of fever, headache, and stiff neck reliable for bacterial meningitis?

What signs and symptoms distinguish meningitis from encephalitis?

What is appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy?

When should a CT scan be done before lumbar puncture?

What cerebrospinal fluid studies are essential, and which ones should be done if the initial studies do not yield a diagnosis?

When is MRI helpful in the diagnosis?

How soon can the patient be discharged, and how long to continue antimicrobial therapy?

When should a neurology consult be obtained?

Introduction

Meningitis and encephalitis may be the most terrifying diseases in medicine. Bacterial meningitis and viral encephalitis may be rapidly fatal, even in healthy persons. Survivors may suffer lasting neurological sequelae, including memory loss and seizures. Cases of meningococcal meningitis spark great anxiety in both caregivers and casual contacts. Viral meningitis, by contrast, gives patients a bad headache and a stiff neck, but uneventful recovery is the rule.

In the United States, bacterial meningitis affects 1.5 to 2.0 per 100,000 population annually, viral meningitis approximately 14 per 100,000 annually, and encephalitis 7 per 100,000 annually. Encephalitis generally refers to viral encephalitis, although bacteria, parasites, spirochetes, and fungi may all cause encephalitis. In this chapter, encephalitis refers specifically to viral encephalitis.

Clinical Presentation

A 43-year-old woman presents with complaints of fever of 103°F, headache, nausea, vomiting, and photophobia. In the emergency department, she becomes increasingly lethargic.

The classic triad of meningitis is fever, headache, and stiff neck (nuchal rigidity). Patients with bacterial meningitis may also have an altered level of consciousness. Almost all patients with bacterial meningitis have at least two of these features, so the absence of all four makes bacterial meningitis unlikely. Patients may also complain of photophobia, nausea, and vomiting.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to exclude bacterial meningitis based on the physical examination. Findings may include nuchal rigidity (pain on passive flexion of the neck), Kernig’s sign, and Brudzinski’s sign. Kernig’s sign is elicited with the patient in the supine position. The thigh is flexed on the abdomen with the knee flexed. Attempts to passively extend the leg cause pain when meningeal irritation is present. Brudzinski’s sign is elicited with the patient in the supine position, and is positive when passive flexion of the neck results in flexion of the hips and knees. Patients with bacterial meningitis may also have focal neurological deficits or seizures.

Less than 50% of children with bacterial meningitis have nuchal rigidity. The possibility of bacterial meningitis should be considered in every child with fever, vomiting, photophobia, lethargy or altered mental status. Many cases of bacterial meningitis in children are preceded by upper respiratory tract infections or otitis media. Signs of meningitis in the neonate are nonspecific, and include irritability, lethargy, poor feeding, vomiting, diarrhea, temperature instability (fever or hypothermia), respiratory distress, apnea, seizures, and a bulging fontanel.

Patients with viral meningitis complain of fever, headache, stiff neck, photophobia, nausea, and vomiting, but are awake and alert.

|

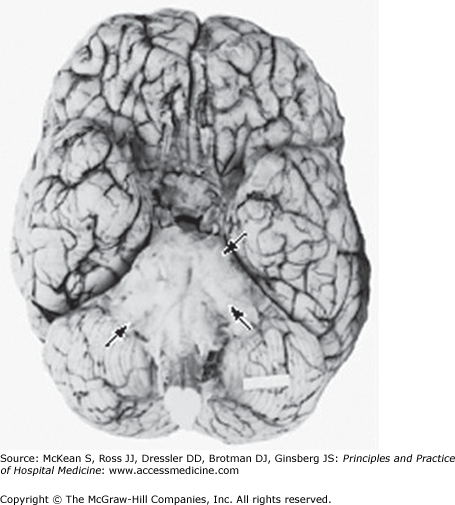

Tuberculous meningitis presents as either a slowly progressive illness with persistent and intractable headache that has been present for weeks followed by confusion, lethargy, meningismus, focal neurological deficits and cranial nerve deficits, or an acute meningoencephalitis characterized by coma, raised intracranial pressure, seizures and focal neurological deficits. The basilar meninges are predominantly involved (Figure 199-1). Fungal meningitis clinically resembles tuberculous meningitis. Patients complain of headache, fever and malaise, followed by meningeal signs, altered mental status and cranial nerve palsies.

Etiology

Pathogens causing meningitis depend upon age and predisposing or associated conditions (Table 199-1). Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of meningitis in adults older than 20 (45–50% of cases). Infection may begin with pneumonia, otitis media, or sinusitis. Meningococci are directly spread by large droplet respiratory secretions, and tend to infect adolescents who share cigarettes, cokes and kisses. Listeria monocytogenes (about 8% of cases) is a food-borne infection, found in sources as diverse as processed meats, unpasteurized cheeses, cheese balls, hot dogs, and raw vegetables. Neonatal bacterial meningitis infections are acquired from the maternal genitourinary tract.

| Predisposing Condition | Bacterial Pathogen |

|---|---|

| Neonate | Group B streptococcus, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes |

| Healthy children and adults with community acquired disease | Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis |

| Otitis, mastoiditis, sinusitis | Streptococci sp, gram-negative anaerobes (Bacteroides sp, Fusobacterium sp), Enterobacteriaceae (Proteus sp, E coli, Klebsiella sp), staphylococci, Haemophilus influenzae |

| Adults over age 55 or with chronic illness | S pneumoniae, N meningitidis, gram-negative bacilli, L monocytogenes, H influenzae |

| Postneurosurgical or intraventricular device | Staphylococci, gram-negative bacilli |

| Endocarditis | Viridans streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus bovis, HACEK group, enterococci |

|

The most common etiological agent of aseptic meningitis are viruses. Enteroviruses (including coxsackievirus, echovirus, and enteroviruses 68–71) have been found in more than 75% of cases in which a specific pathogen is identified. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) and HIV are also fairly common etiological agents of viral meningitis. Approximately 25% of women and 11% of men develop meningitis during the primary episode of genital herpes, with up to 20% of these patients having recurrent attacks of meningitis (Mollaret meningitis). Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses), such as West Nile, can cause meningitis or encephalitis. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus causes a prolonged aseptic meningitis syndrome.

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) is the most important cause of sporadic encephalitis in immunocompetent adults, and the most common cause of viral encephalitis in developed countries. The arboviruses are viruses transmitted by the bite of a mosquito or tick. The most common arboviruses causing encephalitis in North America are West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and La Crosse virus.

Varicella zoster virus may cause encephalitis in association with shingles, months after shingles, and in the absence of shingles. Epstein-Barr virus may cause encephalitis as an acute complication of mononucleosis. Cytomegalovirus causes encephalitis in the immunocompromised.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of bacterial meningitis includes viral meningitis, fungal meningitis, tuberculous meningitis, viral encephalitis, and an infectious mass lesion. Subarachnoid hemorrhage may also present with headache and stiff neck.

The differential diagnosis of viral meningitis includes partially treated bacterial meningitis, fungal meningitis, tuberculous meningitis, Lyme disease, drug-induced meningitis (NSAIDs, intravenous immunoglobulin, sulfa drugs, isoniazid, and muromonab-CD3), carcinomatous meningitis, lymphomatous meningitis, and sarcoidosis.

The differential diagnosis of viral encephalitis includes the other etiological agents of encephalitis: bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, Rickettsia, protozoa and parasites. Encephalitis may also be an autoimmune illness, such as nonvasculitic autoimmune inflammatory meningoencephalitis (Hashimoto encephalopathy), a paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis, or a para- or postinfectious disorder, such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

Diagnosis

The first step in the diagnosis of meningitis is physical examination, followed by CBC with differential, C-reactive protein, and blood for Gram’s stain and culture. Antimicrobial therapy is initiated at this step. When bacterial meningitis is suspected, always start empiric and adjunctive therapy immediately after obtaining CBC and blood cultures. Do not wait for the results of spinal fluid analysis to initiate antimicrobial therapy.

Serum procalcitonin (if available) is one of the most sensitive labs for distinguishing between bacterial and viral meningitis. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein (> 40 mg/L) are significantly higher in patients with bacterial meningitis than in those with viral meningitis.

Although every patient with suspected meningitis or encephalitis needs an LP for spinal fluid analysis, not every patient needs a CT prior to an LP. Table 199-2 lists the indications for CT prior to LP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree