Introduction

Medical malpractice is a serious concern for many physicians and a topic that often prompts intense debate. In this chapter, we review the elements of medical malpractice, as well as data about the frequency of both negligent medical care and actual claims of medical malpractice. Data that exist about how well the malpractice system does in achieving its purpose of deterring negligent medical care and compensating patients who are harmed by such negligence are reviewed. We also discuss malpractice issues that are of particular concern to hospitalists, and, most crucially, what can be done to try to reduce the risk of being the subject of a medical malpractice claim.

The Elements of Medical Malpractice

Medical malpractice is a form of negligence that applies to health care providers including doctors, nurses, and institutional medical care providers like hospitals. At the core of negligence-based liability is the notion that individuals committing unintentional but reasonably avoidable acts that cause injury should be required to compensate the victims of those acts. To determine whether negligence is present in a given situation, courts require plaintiffs to prove four elements through a preponderance of the evidence: duty, breach, causation, and harm.

To determine whether negligence is present in a given situation, courts require plaintiffs to prove four elements through a preponderance of the evidence: duty, breach, causation, and harm.

|

The duty of care in negligence claims is a hypothetical standard by which the court judges the conduct of the defendant to determine whether he or she had an obligation to act differently. In the hospital setting, physicians have a duty to provide care with the same skill and diligence as a reasonably competent physician in the same specialty or field of practice would under similar circumstances. Failure to meet this standard constitutes a breach of the physician’s duty of care. In most cases, for this duty to exist, a physician-patient relationship must have been established.

In order to determine whether a physician has breached the duty of care, an expert witness must testify as to the applicable standard in court. In the majority of states, physicians are judged by a national standard of care that all physicians in the same specialty would be expected to follow. However, in a significant number of states, physicians are judged by what other physicians in the same specialty and in the same geographic area would have done in a particular situation. In either case, the relevant testimony must come from expert witnesses who have the education, training, or other credentials that would make them familiar with the applicable standard of care. The question of whether a physician breached the duty of care then, often hinges on competing testimony provided by expert witnesses as to the applicable standard of care and whether the conduct in question failed to meet that standard.

Even if a physician breaches this duty by failing to adhere to the standard of care, the plaintiff in a case cannot establish liability unless that breach is the actual cause of the injury. To establish legal causation, the plaintiff must show that the breach was both the “cause in fact” and the “proximate cause” of the injury. As articulated by Louisell et al., a breach of the duty of care is the “cause in fact” of damages if the plaintiff can establish that the presence of the breach was the “deciding factor” in determining whether the damage would have occurred. Put differently, a breach of the duty of care would not be the “cause in fact” of harm if the harm would have occurred despite the negligent care of a physician. In addition to being the cause in fact of harm, a breach of the duty of care must also be the proximate cause in order to satisfy the causation element of negligence. To be the proximate cause of harm, the harm must be, by its nature, a foreseeable or direct consequence of a breach of the duty of care. Some courts require an additional or alternative finding that the breach was a “substantial factor” in causing the injury, especially when two or more parties may be responsible.

If the court or jury finds that a physician has breached a duty by failing to adhere to the applicable standard of care and that the breach is the cause in fact and proximate cause of a patient’s injury, then the physician will be liable for damages. The measure of such damages is often highly dependent on the facts and circumstances surrounding the particular incident. Generally, a claimant can recover compensatory damages for both economic and noneconomic harm. Economic damages include current and future loss of earnings and the specific costs associated with treating the injury such as medical bills and drug expenses. Economic damages also include the costs of living with the injury such as modifications to the home to accommodate a wheelchair. Noneconomic damages most often include pain and suffering (physical and emotional) from the injury. In addition, courts may order punitive damages for injuries that are the result of malicious conduct or a willful disregard of patient safety. However, such instances are relatively rare.

Medical malpractice claims usually involve numerous medical personnel involved in every stage of the patient’s care. Malpractice plaintiffs cast a wide net when filing suit for a number of reasons. First, it is often cost prohibitive to file an individual suit against each defendant because of the increased costs of legal discovery. Second, because most states employ a comparative negligence standard (meaning that total damages are calculated and then allocated to defendants based on their percentage of contribution of fault), it is difficult to allocate damages among separate claims. It is also more likely that naming multiple defendants will help the plaintiff narrow down which of the defendants was actually at fault (if any). Third, joining multiple defendants in the same suit allows plaintiffs to use the defendants’ own knowledge and testimony to establish standards of care, cutting down on the costs of hiring independent expert witnesses. Finally, there may be jurisdictional rules that prohibit separate claims and require naming all the responsible parties in a single claim if a failure to do so would result in an unfair outcome or an increased burden on the judicial system.

Information concerning the extent of medical malpractice is limited because of the inherent difficulties in identifying adverse events and determining which cases were the result of negligence. More reliable data may be obtained on the number of paid malpractice claims, since insurance companies are required to report them to a national database. However, malpractice claims are a crude measure of malpractice patterns because there is a poor correlation between negligence and claiming.

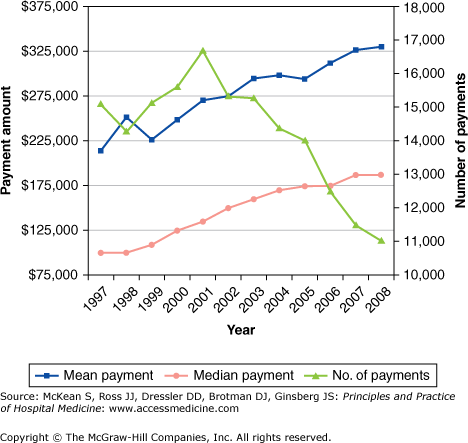

Overall, therefore, an analysis of malpractice trends is limited by the quality of the underlying data. Despite such limitations, there are some sources of data that can provide insight into trends regarding the payments made for malpractice. One useful source of information on medical malpractice is the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), which was established by the Health Care Quality Improvement Act of 1986. The Act was intended to improve the quality of medical care, in part by requiring the submission of malpractice claims to the NPDB, which can then be referenced by health care institutions when making hiring decisions. Based on NPDB data, Figure 36-1 shows trends regarding the number of payments, the median payments, and the mean payments for medical malpractice for the period 1997–2008.

Some studies have analyzed the epidemiology of medical injury in specific states. Examining more than 30,000 records of patients hospitalized in New York State in 1984, the Harvard Medical Practice Study is the largest study to assess the rate of medical malpractice injuries and claims. In this study, Brennan et al. showed that adverse events occurred in 3.7% of hospitalizations and of these adverse events, 27.6% were determined to be due to negligence. In a further analysis of the Harvard Medical Practice Study by Localio et al., the overall rate of malpractice claims per discharge was 0.13%. In this study, the vast majority of adverse events did not result in a malpractice claim. Of the adverse events due to negligence that were identified, remarkably, only about 2% resulted in malpractice claims. The estimated ratio of negligence to claims was 7.6 to 1.

Testing the generalizability of the results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study, a subsequent, methodologically similar study by Thomas et al. examined 15,000 hospital records from Utah and Colorado. In this study, which yielded comparable results to the Harvard Medical Practice Study, 2.9% of hospitalizations in each state involved adverse events. Of these adverse events, 32.6% were a result of negligence in Utah, and 27.4% were a result of negligence in Colorado. Additional analysis of these data by Studdert et al. in 2000 showed that only about 3% of those patients who suffered a negligent injury filed a malpractice claim. Characteristics more common among patients who suffered negligence but did not file a malpractice claim include low income, uninsured, insured by Medicare or Medicaid, and age ≥ 75 years. Of those malpractice claims identified during the study period, 78% were made despite the absence of negligence and 56% were made despite the absence of an adverse event. The ratio of negligent adverse events to claims was 5.1 to 1 in Utah and 6.7 to 1 in Colorado.

The two main purposes of the medical malpractice system are to compensate patients who suffered injuries resulting from negligence, and to deter negligent behavior by imposing costs on physicians who practice negligently. These data call into question whether the medical malpractice system is achieving these objectives. Given the large number of adverse events due to negligence not leading to a malpractice claim, the medical malpractice system is not efficient at holding negligent physicians accountable, and many patients who have been injured as a result of malpractice are not receiving compensation. One implication of these data is that the rate of claims is a problematic metric to use in assessing quality of care, since most episodes of negligence do not lead to malpractice claims, and a significant number of malpractice claims are filed in the absence of negligence or injury.

A somewhat different picture emerges when the outcomes of claims are analyzed, rather than simply the filing of claims. Studdert et al. in 2006 evaluated 1452 closed malpractice claims in which objective assessments were made by reviewers as to whether there were medical errors resulting in injury. Of those claims filed involving injuries, 63% were determined to be a result of error. In cases in which there was injury due to error, compensation was paid 73% of the time. In cases in which there were no errors, no compensation was paid 72% of the time. The authors of the study concluded that although the malpractice system does a reasonable job of providing compensation only when there is injury as a result of a medical error, the process has significant shortcomings. Namely, cases take a long time to come to resolution (five years, on average, from injury to disposition) and the monetary costs of litigating the claims are steep (54% of the compensation paid).

Thus the data show a very limited correlation between malpractice claims made and acts of actual malpractice. Based on the 2006 data from Studdert et al., looking at the outcomes of claims, it appears that the majority of claims with merit result in compensation and the majority of meritless claims are denied compensation, which has also been observed in other analyses of outcomes of claims, as summarized by Baker. However, the system of determining which claims have merit is protracted and expensive.

Areas of Medical Malpractice of Special Concern to Hospitalists

Many of the potential areas of malpractice that concern hospitalists relate to the inherent discontinuity between inpatient and outpatient care. These areas include failure to follow up on incidental findings and appropriately addressing test results that may be pending at the time of discharge or may be altered upon final review (e.g., by the attending radiologist or pathologist). This situation is exacerbated by the multiple handoffs of patient care that can occur when hospitalists work shifts. Moreover, in academic medical centers, tests may be ordered by resident physicians and the attending hospitalist may not even be aware that the test was ordered. Given that hospital medicine is a relatively young field with limited case law involving hospitalists specifically, cases applicable to hospitalists may be drawn from other fields of medicine in which physicians have temporary relationships with their patients, such as emergency medicine.

FAILURE TO FOLLOW UP ON AN INCIDENTAL FINDING A 62-year-old male with a significant smoking history presented to the emergency department (ED) in November 1999 after a fall resulting in a left shoulder injury. The ED physician took X-rays of the chest and left shoulder, read them as showing no fracture, and discharged the patient home. Four days later, the attending radiologist read the X-ray as showing a left lung nodule, and a report of the X-ray was sent to the ED physician and primary care physician (PCP). The radiologist did not call either the ED physician or the PCP. The patient saw his PCP twice in December 2000 for back and shoulder pain and was sent for physical therapy. The patient presented to the ED in August 2001 with chest and shoulder pain. A chest X-ray was obtained, which the ED attending read as normal, but the radiologist noted a large mass in the left lung. This information was not conveyed to the patient’s PCP. After another visit to his PCP in September 2001, the patient presented to the ED again in October 2001 with back and chest pain, and a chest X-ray showed a mass occupying the majority of his left lung. The patient died of metastatic disease soon thereafter. The patient’s children filed suit against the PCP, ED physician, and radiologist, and the suit was settled for more than $500,000. Adapted from Wright J, McCormack P. Failure to act on incidental finding. CRICO Forum 2007;25:6–7. |

The preceding case illustrates the liability pitfalls that can result from inadequate communication among the physician ordering a radiologic study (the ED physician), the physician interpreting the study (the radiologist), and the physician who is best suited to follow up on the abnormal results (the primary care physician). This case had features that are common in ED cases leading to malpractice claims, as elucidated by Kachalia et al., including the misreading of plain radiographs, the involvement of multiple individual failures, and process breakdowns.

Hospitalists frequently find themselves in the same position as the ED physician in the above case, ordering a study the final results of which may not come back until after the patient has been discharged. The same problem applies to laboratory tests. One study by Roy et al. encompassing the hospitalist services at two academic medical centers found that 41% of patients had laboratory or radiology results pending at the time of discharge and in 9.4% of cases the results of these studies were considered potentially actionable. Seventy percent of the inpatient physicians and 45.8% of the outpatient physicians were unaware of these potentially actionable results.

The problem of pending test results at the time of discharge is best addressed at a systems level—for example, through a mechanism that automatically notifies the ordering provider of the final results of such tests. However, such systems are not widely in place and even when they are, physicians still often fail to follow up on clinically significant results. Consequently, physicians need to take responsibility for following up on the final results of the tests that they order.

Physicians may also be held responsible for responding to test results ordered by another physician when these results come back while that physician is on duty, as was held in Siggers v. Barlow (906 F.2d 241). Responding to these test results often means communicating with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) about what additional follow-up needs to occur, such as the need for serial imaging for an incidentally discovered pulmonary nodule. Discharge summaries, while important, are generally not adequate as the only means of communicating important findings that need to be followed up by the PCP. Kripalani et al. and Pantilat et al. identified a number of potential deficiencies in the discharge summary as the sole means of communicating with the PCP. These deficiencies include the possibility that the discharge summary does not reach the correct PCP (occurring 25% of the time), failure to include tests pending at discharge (occurring 65% of the time), and the PCP not receiving the discharge summary prior to follow-up (occurring 67% of the time). Therefore, hospitalists should contact PCPs directly regarding important test results or other matters that need to be followed up, by phone and/or letter, and this communication should be documented in the patient’s chart.

The number of malpractice cases involving hospitalists specifically is not well documented, given that hospital medicine has not been recognized as a distinct specialty and so tallies of malpractice cases are usually not broken down by involvement of a hospitalist. Moreover, as with all malpractice cases, many cases involving hospitalists may be settled prior to trial, and so no public record of the matter may be generated. Reports to the National Practitioner Data Bank contain only limited details about cases. Despite these limitations, the few reported cases involving hospitalists are instructive in illustrating potential areas of malpractice liability distinct to hospitalists. These areas may not be captured by analyses relying on fields thought to have analogous malpractice liability concerns, such as emergency medicine.

One such potential area of malpractice liability concerns the use and coordination of consultants. Hospitalists list active coordination of consulting specialists as one of the benefits they bring to patient care. However, with this responsibility for coordination of specialists, and in their role of the attending physician of record for the patient, hospitalists are at risk of incurring malpractice liability based on the actions of the consulting specialists.

DOMBY V. MORITZ (2008 CAL. APP. UNPUB. LEXIS 1856) A 67-year-old female with a history of hypertension checked her own blood pressure, found that it was elevated, and contacted her PCP. As instructed by her PCP, the patient took an extra dose of atenolol, after which she had an episode of syncope. She presented to the hospital, where she was bradycardic and so the ED physician gave the patient atropine and glucagon to reverse the effects of the atenolol. A partner of the patient’s cardiologist was contacted and advised to put an external pacemaker on the patient, but the cardiologist did not see the patient. The patient was admitted to the ICU by a hospitalist. In anticipation that an internal pacemaker might be needed, the hospitalist reversed the patient’s coumadin with fresh frozen plasma. The ICU nurses called the cardiologist to report that the patient was bradycardic and feeling unwell. The cardiologist never placed an internal pacemaker. The hospitalist was next contacted by the ICU nurses once the patient was in cardiac arrest. The patient’s family filed suit against both the cardiologist and the hospitalist. The court ultimately found in favor of the hospitalist. |

The preceding case, Domby v. Moritz (2008 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 1856), illustrates this risk. In filing suit against both the cardiologist and the hospitalist, the family of the patient asserted that the hospitalist should have ensured that the cardiologist physically came in to evaluate the patient. Although the court ultimately found in favor of the hospitalist, this case illustrates that hospitalists have to take an active role in discussing the treatment plan with consultants and in clearly delineating who has responsibility for which aspects of the patient’s care. It can be legally hazardous to consider a clinical decision “not my call” and exclusively within the purview of a specialist, because the hospitalist, as the attending physician of record, can face litigation based on the decisions made by the consulting specialists.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree