Normal Physiology

Penile erection is a hemodynamic process mediated by the integration of highly specialized neural and vascular mechanisms that control the rate of blood flow into and out of the highly vascular corpora cavernosa, which constitute the bulk of the penile shaft. Blood flow is modulated by changes in the contractile state of the trabecular smooth muscle lining the corporal arterioles and sinusoids. In the flaccid state, trabecular smooth muscle tone is high, and arterial flow into the penis is minimal. Venous outflow is facilitated by copious arteriovenous shunts. With sexual stimulation, the smooth muscle relaxes, arterioles dilate, and blood flows in, engorging the corporal sinusoidal spaces. This engorgement compresses the arteriovenous shunts and venular plexuses between the trabeculae and the fibrous tunica albuginea, markedly impairing venous outflow. The result is an intracavernosal pressure of 100 mm Hg and what is termed a full erection. Intercourse or masturbation elicits the bulbocavernosus reflex, with the ischiocavernous muscles compressing the base of the engorged corpora cavernosa, driving intracavernous pressure to several hundred millimeters of mercury. During this phase of rigid erection, the penis is at its hardest as the flow of blood comes to a temporary standstill. When ejaculation occurs, a sympathetic discharge leads to contraction of the trabecular smooth muscle, reopening the venous channels and releasing the trapped blood, rendering the penis flaccid. Both autonomic and somatic nerves control this sequence of events. Sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves merge in the pelvis to form the cavernous nerves, which regulate blood flow. Somatic innervation of the dorsal nerves, which derive from the pudendal nerve, is responsible for penile sensation and for the functioning of the bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernous muscles.

Control Centers and Mechanisms

There are two spinal erection centers. The sympathetic reflex center is situated in the thoracolumbar (T-12 to L-2) region. It controls adrenergic tone and sustains the vasoconstriction of the flaccid state. The parasympathetic reflex center occupies the midsacral (S-2 to S-4) region. The vascular changes responsible for erections can be triggered by one or more of three mechanisms, referred to as psychogenic, reflexogenic, and centrally originated. Psychogenic erections occur in response to erotic sensations and the related stimulatory pathways (e.g., sight, touch, smell, sound) that travel from the spinal erection centers and induce dopaminergic initiation of the erection sequence from the medial preoptic area. Reflexogenic erections are produced by direct tactile stimulation of the penis. In most instances, these two mechanisms are synergistic. Centrally originated erections, also referred to as nocturnal erections, are seen during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and reflect a decrease in baseline sympathetic inhibition.

Mediators

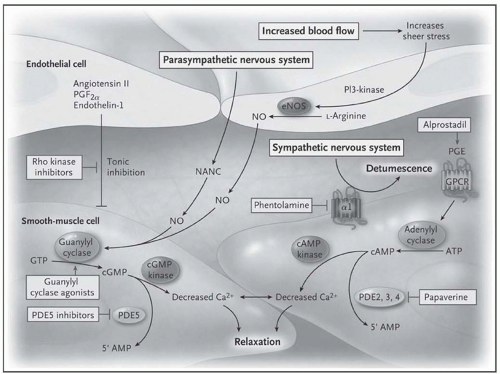

Mediators of erection and the erection pathway at the cellular level are illustrated in

Fig. 132-1. In the flaccid state, penile vascular smooth muscle is maintained in a semicontracted state by baseline myogenic tone, adrenergic stimulation, and

endothelium-derived relaxing factors. Parasympathetic stimulation associated with sexual stimulation increases the concentration of

nitric oxide in smooth muscle cells, thereby mediating the vasodilation of penile erection. High concentrations of nitric oxide are delivered to the trabecular smooth muscle by the cavernous nerves. In addition, cholinergic output stimulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase, causing an increased production of nitric oxide. The nitric oxide diffuses across the smooth muscle membrane, where it activates guanylate cyclase, stimulating the production of

cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which ultimately reduces cytosolic calcium concentration, causing cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation. The pathway is regulated by

phosphodiesterase enzymes that inactivate cGMP. PDE-5 is the most important isozyme in the corpora cavernosa. A separate mechanism mediated by

cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) also decreases intracellular calcium levels.

The balance between parasympathetic and adrenergic stimulation necessary for normal erectile function offers insight regarding some of the common correlates of dysfunction. Patients with diabetes, depression, and central and peripheral neuropathic diseases have impaired parasympathetic output. Men who smoke have an increase in outflow from the sympathetic nervous system that inhibits the relaxation necessary for erection. It is believed that adrenergic output is impaired in men with lower urinary tract symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Hormonal influences include the role of

testosterone as a stimulant of sexual activity and a regulator of penile erectile physiology, manifesting influences on penile nitric acid synthesis, venous occlusion, penile blood flow, and smooth muscle mass. Unappreciated are the wide variations in the amount of

testosterone needed to sustain sexual function in men and the important role of testosterone-derived estrogen.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentations

Impairment of any element of the erectile apparatus or its control can lead to ED. Obvious organic causes are injury to the reflex centers in the spinal cord, severance of cortical input, and injury to the peripheral nerves and/or vascular apparatus through trauma or surgery. Less obvious and much more common are multifactorial explanations related to aging and the common agerelated chronic diseases. It has been estimated that among men older than 50 years with ED, at least 40% of cases were attributable to atherosclerosis. One attempt to categorize organic causes of ED concluded that 40% were due to atherosclerosis separate from diabetes, 30% to diabetes, 15% to medication, 6% to pelvic surgery or trauma, 5% to neurogenic causes, 3% to endocrine disease, and 1% to other conditions. Psychological factors and the effects of drugs are also frequently involved.

The Aging Male

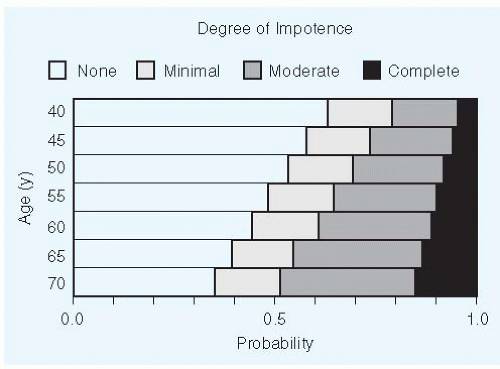

ED is strongly associated with age. Roughly 20% of men in their early 40s report moderate or complete ED. By the early 70s, that number has grown to 50% (

Fig. 132-2). Serum testosterone declines gradually with age. Reductions associated with reduced sexual function (e.g., < 200 ng/dL) can be found in 20% of men by age 60 years and in 50% of men by age 80 years. (What happens to estrogen levels, which may also be important, remains to be established). In addition, there are concentrations of elastic fibers and smooth muscle fibers decrease as a man grows older. Sensitivity of the penis decreases with age as do levels of penile nitric oxide. However, it is not clear how much ED is attributable to normal aging in the absence of disease. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, submissive personality, obesity, and lower educational attainment are all associated with higher risk.

Vascular Disease

Arterial insufficiency is usually listed as a leading cause of ED in older men. Unexplained, progressive slowing of erection followed by decreased rigidity can be among the first symptoms of aortoiliac vascular disease when plaque obstructs the iliac arteries immediately distal to the aortic bifurcation. ED develops in almost 40% of men with stenosis and nearly 75% of those with occlusion. Symptoms of claudication in association with ED, aortic or femoral bruits, and diminished peripheral pulses describe Leriche syndrome. In some cases, the patient has the ability to initiate an erection but cannot maintain it. Patients with hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia or who smoke are at increased risk for the compromise of penile perfusion by atheromatous disease. Radiation therapy and pelvic trauma are other risk factors for vascular injury. Venous dysfunction can be equally important and result from age- or lipid-induced loss of venous fibroelastic compressibility. Several authorities argue that venous dysfunction may be more important than previously suspected.

Diabetes Mellitus

ED may be the presenting symptom of diabetes and is reported in up to 50% of men with the disease. Autonomic neuropathy resulting in failure of the pathways leading to vasodilation is the principal problem. In addition, endothelium-derived relaxing factor becomes deficient. Occlusive disease of larger vessels plays a much less important role than was previously believed, although it does play an important role in some cases. The risk for ED appears to parallel the duration and severity of diabetes. With conventional means of achieving glucose control, the majority of diabetic men experience some degree of ED, with fewer than 10% achieving restoration of normal function. Aggressive control of type 1 diabetes has effected a marked reduction in the risk for the development of autonomic neuropathy. The forerunner of ED in the diabetic is often retrograde ejaculation. The presence of dry orgasm or milky postcoital urine augurs a loss of erectile function within 1 year.

Pelvic Surgery or Trauma and Other Neurogenic Causes

Damage to either central or peripheral nerves can cause ED. Stroke, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease cause a decrease in libido and an overinhibition of spinal centers.

Radical prostate, bladder, or

colorectal surgery can produce ED as a result of surgical damage to the pelvic autonomic nerves. The incidence of radical prostate surgery has increased dramatically in recent decades due to increased clinical detection of prostate cancer. Improved understanding of the course of these autonomic fibers has led to revised surgical techniques, such as

nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy to lower the risk for ED. Some surgeons have reported good results, but the procedure cannot be performed in all cases (see

Chapter 143.). Neurogenic ED can also be caused by radiation therapy, which is also increasingly used for prostate cancer.

After radical

retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular tumors, ejaculatory failure may develop in young men as a result

of bilateral resection of the paraaortic sympathetic ganglia, but ED rarely develops.

Bilateral sympathectomy of lumbar ganglia at L-1 will inhibit ejaculatory capacity, but not orgasmic sensation, in more than half of cases. More than 75% of all men with

spinal cord injuries demonstrate some erectile capacity, but only 25% are able to engage successfully in intercourse. The erection is reflexogenic, requiring continued penile stimulation to be maintained. Erections are totally abolished when local destruction of spinal segments S-2 to S-4 or their roots is complete. Again, the higher the location of the lesion, the better are the chances of a good erection. Ejaculation is rare when the lower thoracic and upper lumbar segments (approximately to L-3) of the cord are so extensively damaged that the nearby sympathetic components are destroyed. Sexual sensation is abolished with transection anywhere above the sacral level. Herniated intervertebral disks and metastatic cancer of the vertebral column, especially between T-10 and L-5, which cause local swelling and destruction of spinal cord tissue, may produce a similar clinical picture.

Endocrine Diseases

Testosterone deficiency can contribute to male sexual dysfunction, predominantly by decreasing interest in sexual activity and perhaps by impairing normal erectile physiology. Results from studies of replacement therapy in men with testosterone deficiency are equivocal with regard to improvement in erectile function; sexual activity scores rise, but effect on erectile function per se is less definitive. Such findings raise the question of testosterone’s specific relevance to ED and the need for attention to its treatment in men with ED (see later discussion). Causes of testosterone deficiency include advancing age; chromosomal, pituitary, and testicular disorders; and antiandrogen therapy. Manifestations include regression of secondary male sex characteristics, along with feeble libido and waning potency. When the cause is testicular failure, gonadotropin levels will be very high; when a pituitary or hypothalamic cause is present, gonadotropin levels will be low.

Hyperprolactinemia is an important source of pituitaryderived ED. Serum testosterone levels fall as gonadotropins decline, although ED seems to be more closely related to the degree of prolactin elevation. A reduction in prolactin restores erectile function. Hyperprolactinemia may be idiopathic, the result of a functioning pituitary adenoma, or a consequence of

hypothyroidism (stimulated by high levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone; see

Chapter 100).

Addison disease tends to lead to loss of libido and ED. Cushing syndrome, except when associated with adrenal carcinoma, impairs libido and potency after an initial period (weeks or months) of marked increase. Acromegaly leads to an early impairment of potency and a premature extinction of function. The decline in function is frequently preceded by a hyperlibidinal period.

Prostatic Disease

BPH and resulting lower urinary tract symptoms are very common among men in age groups most at risk for ED. A number of recent studies suggested an association between BPH and ED, but the pathophysiologic relationship between the two is unclear. Increased sympathetic outflow and impaired nitric oxide content in the penis, prostate, and bladder have been described as possible explanations. Early evidence suggests that PDE-5 inhibitor therapy may improve urinary function, as well as erectile function.

ED may be the first symptom of prostate cancer. Advancing centrifugal growth of neoplastic tissue in the posterior lobe of the prostate may induce local swelling and destruction of the parasympathetic fibers that run along the posterolateral aspect of the prostate. Prostatitis may cause painful ejaculations and even hematospermia. Premature ejaculation and postcoital fatigue occur, but ED is not characteristic.

Other Causes

Pelvic fracture, resulting from a crash injury in which the posterior urethra is ruptured, causes ED in 25% to 30% of cases. Nonperformance may result from painful intromission associated with Peyronie disease, balanitis, acute gonorrhea, herpes genitalis, or phimosis. Hypospadias with a chordee of the shaft can preclude intercourse. With priapism, erection may be only partial and insufficient for intercourse because irreversible fibrosis of the corpora cavernosa has occurred. A large hernia or hydrocele may mechanically interfere with coitus, although potency should remain intact.

Psychogenic Conditions

Anxiety and depression are potent precipitants of ED. The marked sympathetic outflow that accompanies anxiety increases alpha-adrenergic tone and impedes trabecular smooth muscle relaxation. In addition, cortical influences may inhibit sacral cord reflexes that would normally trigger erection by way of parasympathetic stimulation (see

Chapter 229). Performance anxiety, relationship problems, and stress are often contributors.