CHAPTER 10 McKenzie Method

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Exercise, loosely translated from Greek, means “freed movement” and describes a wide range of physical activities. Therapeutic exercise indicates that the purpose of the exercise is for the treatment of a specific medical condition rather than recreation. The main types of therapeutic exercise relevant to chronic low back pain (CLBP) include (1) general physical activity (e.g., advice to remain active), (2) aerobic (e.g., brisk walking, cycling), (3) aquatic (e.g., swimming, exercise classes in a pool), (4) directional preference (e.g., McKenzie), (5) flexibility (e.g., stretching, yoga, Pilates), (6) proprioceptive/coordination (e.g., wobble board, stability ball), (7) stabilization (e.g., targeting abdominal and trunk muscles), and (8) strengthening (e.g., lifting weights).1 The management section of this chapter focuses exclusively on directional preference exercises related to the McKenzie method, which are determined through the McKenzie assessment process.

The McKenzie method is a comprehensive approach to spinal pain, including CLBP, which includes both an assessment and an intervention consisting primarily of directional preference exercises. The goal of the McKenzie assessment is to classify patients with CLBP according to the type of therapy to which they are most likely to respond. Because it combines assessment and intervention, the McKenzie method is commonly referred to as mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT).2 One of the principal tenets of MDT is centralization, which refers to the sequential and lasting abolition of distal referred symptoms, as well as subsequent abolition of any remaining spinal pain in response to a single direction of repeated movements or sustained postures.

Because the direction that can achieve centralization can differ among patients with CLBP, the McKenzie assessment attempts to uncover a patient’s directional preference. Directional preference refers to a particular direction of lumbosacral movement or sustained posture that results in centralization or a decrease in pain while returning range of motion to normal.3 The opposite of centralization is peripheralization, which can occur if distal referred symptoms increase in response to a particular repeated movement or sustained posture.4 Whereas centralization should be encouraged, peripheralization should be avoided. Many clinicians use only the intervention component of the McKenzie method, without the McKenzie method of assessment. It is preferable in such instances to identify the intervention descriptively (e.g., repeated prone lumbar extension) rather than referring to them as McKenzie exercises, which denotes a paired assessment and matched intervention approach. This point is very important in light of the frequency with which the McKenzie method has mistakenly been reduced and equated with lumbar extension exercises.

According to MDT, patients may be classified into one of three mechanical syndromes: derangement, dysfunction, or postural.5,6 Derangement syndrome is the most common, and indicates that centralization can be achieved with directional preference movements. Dysfunction syndrome is found only in patients with chronic symptoms and is characterized by intermittent pain produced only at end-range in a single direction of restricted movement. Adherent nerve root is a particular type of dysfunction that typically follows an episode of radicular pain after which pain can be elicited when the nerve root and its adhering scar tissue are stretched. Postural syndrome is likewise intermittent, but pain is typically midline or symmetrical, produced only by sustained slouched sitting, and subsequently abolished by posture correction (restoring the lumbar lordosis); it is typically not seen in CLBP. The minority of patients who cannot be classified into one of these three syndromes would be termed other.

History and Frequency of Use

In 1958, a patient with low back pain (LBP)-related leg symptoms presented to a physical therapy clinic in Wellington, New Zealand, and inadvertently lay prone in substantial lumbar extension for a prolonged time (approximately 10 minutes), after which he reported to the clinician (Robin McKenzie) that his leg had not felt this good for weeks (Figure 10-1). Surprised and intrigued by this event, McKenzie began experimenting with sustained and repeated movements of the lumbar spine for various spinal symptoms, including LBP. This fortuitous encounter led to the development of MDT. In his own words: “Everything I know I learnt from my patients. I did not set out to develop a McKenzie method. It evolved spontaneously over time as a result of clinical observation.”7

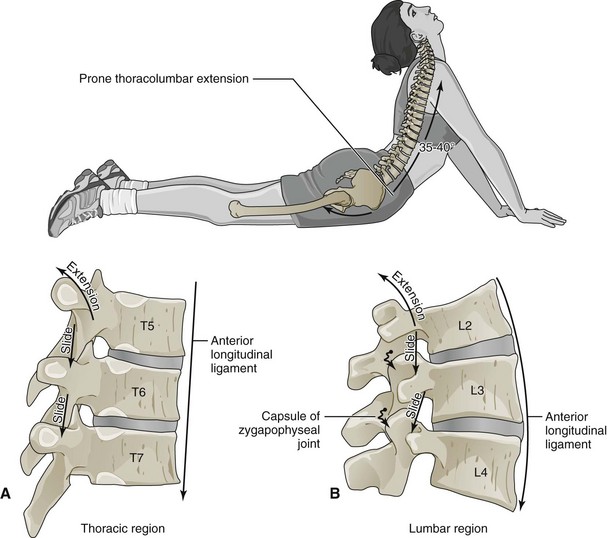

Throughout many years, McKenzie observed patterns of pain response to particular positions and movements and developed a system to classify many spinal pain problems based on those findings. McKenzie was the first clinician to systematically demonstrate the benefits of having patients perform repeated lumbar movements and sustained postures, both to end-range. As long as each direction of lumbar movement was tested repetitively to end-range, McKenzie observed that a single direction would very commonly elicit centralization. A common directional preference exercise for those whose symptoms decrease in extension is shown in Figures 10-2 through 10-4. Treatment with MDT also includes strict temporary posture modifications to avoid loading the lumbar spine opposite to the direction of preference for any length of time.

Figure 10-3 The impact of directional preference exercises on specific lumbar spine anatomic structures is not known.

(From Neumann DA: Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system: foundations for physical rehabilitation. St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

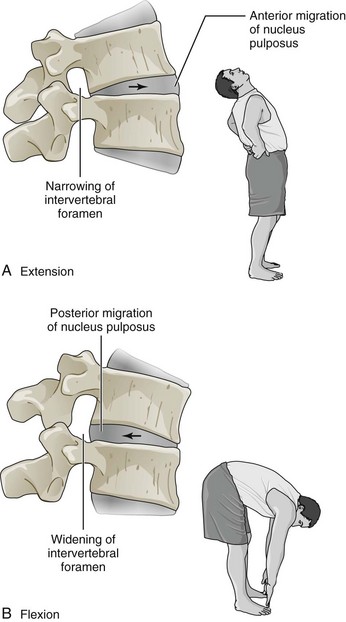

Figure 10-4 The impact of directional preference exercises on specific lumbar spine anatomic structures is not known.

(Modified from Mansfield PJ: Essentials of kinesiology for the physical therapy assistant. St. Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

The overall objective of the McKenzie method is patient self-management and includes educating patients about three components: (1) beneficial effects of specific positions and end-range movements, and the aggravating effects of the opposite movements and postures; (2) maintaining the reduction and abolition of symptoms; and (3) restoring full function to the lumbar spine without symptom recurrence. McKenzie authored several books aimed at helping patients manage their own LBP and neck pain, and these books have been sold worldwide for more than 25 years; companion textbooks for clinicians are also available.8–10 Research into the McKenzie method began in 1990 when the first diagnostic reliability study, randomized controlled trial (RCT), and study of the concept of centralization were published.11–13 Since then, numerous studies have been published every year on the reliability and prognostic validity of the McKenzie assessment, as well as the efficacy of McKenzie method interventions.

Practitioner, Setting, and Availability

Treatment with the McKenzie method is offered through a variety of providers involved in spine care, including physical therapists, chiropractors, and physicians who receive additional training on this approach. The qualification of McKenzie method clinicians is structured, internationally standardized, and educationally validated. Four postgraduate courses and a credentialing examination complete basic training, and for those who wish to pursue more advanced studies, a course, clinical mentorship, and examination are required to be recognized as a McKenzie Diplomat. In seeking competent McKenzie method clinicians for patient referral and research purposes, it is wise to first inquire about their educational credentials for assurance that the all important assessment and classification processes will be performed thoroughly and reliably. Typically, clinicians trained in the McKenzie method can be found in many inpatient and outpatient settings, departments in hospitals, and in private practice. The availability of certified McKenzie method practitioners can be verified with a Web-based database for areas of the United States, Canada, and other countries (www.mckenziemdt.org). The number of spine practitioners who may recommend specific components of the McKenzie method, such as directional preference exercise, far outnumbers those practitioners who are certified in the entire approach.

Procedure

The aim of the assessment is to classify patients into one of three possible mechanical syndromes. The proportion of patients who could be classified has been generally high, with a mean of 87% across five studies.7,11,14–16 For example, 83% of 607 patients were classified in one of the mechanical syndromes, with 78% classified as derangement.17 Pain centralization, a hallmark of the derangement syndrome, has been reported in 52% of 325 CLBP patients.4 Directional preference was elicited in 74% of subjects in an RCT, of which 53% had symptoms duration greater than 7 weeks.18

Theory

Mechanism of Action

In general, exercises are used to strengthen muscles, increase soft tissue stability, restore range of movement, improve cardiovascular conditioning, increase proprioception, and reduce fear of movement. Most McKenzie method exercises are intended to directly and promptly diminish and eliminate patients’ symptoms by providing beneficial and corrective mechanical directional end-range loads to the underlying pain generator.18 The anatomic means by which these rapid pain changes occur is addressed in an article by Wetzel and Donelson.19 Treatment with the McKenzie method may also provide psychological mechanism–related benefits.

Indication

Mechanical Low Back Pain

Patients who may be responsive to the McKenzie method are those whose symptoms are affected by changes in postures and activities (e.g., pain made worse by sitting and bending, but better with walking or moving). Such a history is often indicative of a directional preference for extension, which can be confirmed during the repeated end-range testing of the physical examination. Such mechanical responsiveness to changes in posture and activity has been commonly reported.12,20–23

Centralizers

At least six studies have reported on the favorable prognosis for patients who were categorized as centralizers if treatment is directed by the patients’ directional preference.13,24–28 A systematic review (SR) similarly concluded that centralization, when elicited, predicts a high probability of a good treatment outcome, again as long as treatment is guided by the assessment findings.4 These patients might be considered the most ideal patients to experience an excellent treatment response with this approach. Initial clues for potentially responsive patients emerge during the history taking and then are confirmed with the repeated end-range movement portion of the physical testing.

Assessment

Before initiating the McKenzie method, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. The standardized McKenzie method assessment also includes an examination in which responses to repeated lumbar movements are noted to enable the clinician to make a provisional classification of the patient’s condition. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating this intervention for CLBP. To prescribe the appropriate directional preference exercises consistent with the principle of management according to classification, patients must first be assessed according to MDT, which may also bring awareness of atypical or nonmechanical pain responses that may alert clinicians to the possibility of serious spinal pathology related to CLBP (e.g., red flags).2 Assessment using MDT generally involves observing the effects of repeated and sustained postures on patient-reported symptoms to identify specific directional preference.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found limited evidence that one component of directional preference exercises (i.e., lumbar flexion exercise), when evaluated as a sole intervention outside of the McKenzie method context, was less effective than aerobic exercises with respect to short-term improvements in pain.29 That CPG also found conflicting evidence regarding the efficacy of trunk flexion exercises when compared with trunk extension exercises. However, these findings are not directly applicable to the McKenzie method that encompasses both the assessment and management components described above.

Other Clinical Practice Guidelines

An older national CPG from Denmark in 1999 mentioned the assessment component of the McKenzie method.30 That CPG found moderate evidence to support the use of the McKenzie method assessment as a diagnostic tool and prognostic indicator. That CPG also found limited evidence to support the use of the McKenzie method management component.

Three other non-national CPGs on the management of CLBP have also reported on the McKenzie method. The CPG from the United Kingdom Chartered Society of Physiotherapy in 2006 found weak scientific evidence to support the management component of the McKenzie method.31 The CPG from the Philadelphia Panel on Selected Rehabilitation Interventions in 2001 found evidence of clinically important benefit to support therapeutic exercise.32 The CPG from Quebec in 2006 found evidence that the management component of the McKenzie method was as effective as strengthening exercises with respect to improvements in pain and function.33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree