Fig. 11.1

The conventional concept of traumatic coagulopathy as a secondary process

11.3 Acute Traumatic Coagulopathy

The first landmark report of the existence of acute traumatic coagulopathy (ATC) was in a retrospective study of the admission coagulation results of 1,088 trauma patients transferred to the Royal London Hospital by air ambulance [11]. Twenty-four per cent arrived in the emergency department with a clinically significant coagulopathy already established, and they were four times more likely to die than those presenting with normal clotting parameters. Subsequent studies performed by independent research groups on a total of over 45,000 patients have confirmed the existence of this early coagulopathy [12–17]. All of these studies reported a strong association between acute coagulopathy and mortality and identified it as an independent risk factor for death [12]. It has also been associated with longer intensive care and hospital stays. Patients are more likely to develop acute renal injury [15] and multiple organ failure [14] and have fewer ventilator-free days [13, 14], and there is a trend towards an increased incidence of acute lung injury [14].

Injury severity is closely associated with the degree of acute coagulopathy seen after trauma. In the London study, only 10.8 % of patients with an injury severity score (ISS) of 15 or below had a coagulopathy, compared with 33.1 % of those with an ISS over 15 [11]. This figure increased to 61.7 % for those with an ISS over 45. In a larger German study, a coagulopathy was evident in 26 % of patients with an ISS 16–24, in 42 % of patients with an ISS 25–49 and in 70 % of patients with an ISS > 50, respectively [14]. However, not all patients who are severely injured present with a coagulopathy; tissue trauma alone does not appear sufficient.

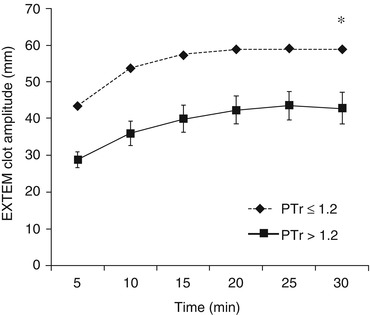

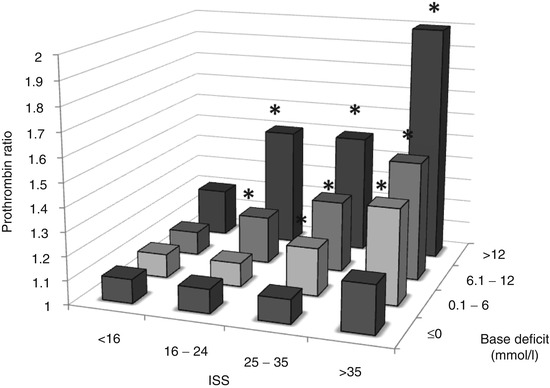

Shock with tissue hypoperfusion is a strong independent risk factor for poor outcomes in trauma [18, 19] and is central to the aetiology of ATC. One study of acute coagulopathy found that no patient with a normal base deficit (BD) had prolonged prothrombin time (PT) or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), regardless of injury severity or the amount of thrombin generated [13]. In contrast, there was a dose-dependent prolongation of clotting times with increasing systemic hypoperfusion. Only 2 % of patients with a BD under 6 mmol/l had prolonged clotting times, compared with 20 % of patients with a BD over 6 mmol/l. The synergistic relationship between tissue injury, systemic hypoperfusion and severity of ATC has been characterised in an observational study of over 5,000 trauma patients [20] (Fig. 11.2).

Fig. 11.2

The relationship between injury severity and shock. Mortality of patients grouped according to ISS and BD. *p < 0.001 compared with ISS < 16, BD ≤ 0 [20]

Whilst it is accepted that tissue injury and systemic hypoperfusion are the principal aetiological drivers of ATC, the pathophysiology remains to be fully elucidated. Advocates of the DIC hypothesis propose that there is a rapid universal depletion of procoagulant factors caused by systemic consumption. However, contemporary evidence would indicate this is not the case. Functional activity of most coagulation factors required for thrombin activation is maintained at levels adequate for haemostasis. A few studies of severely injured trauma patients have identified a pronounced and isolated reduction of factor V down to activities around 30 %, a level consistent with prolongation of clotting times [21–23]. This might be of pathophysiological importance given that activated factor V is a target substrate for lysis by activated protein C. However, endogenous thrombin-generating potential has been reported to be normal or even enhanced in subjects with ATC [24].

Further downstream, clotting factor 1 (fibrinogen) is consistently reported as depleted early in trauma studies [25]. Concentrations below 1 g/dl acutely after injury have been reported, and thromboelastometric analysis frequently identifies an impairment of fibrin polymerisation. Unfortunately, at present, there are no rapidly available point of care tests available to measure circulating fibrinogen concentrations, and the optimal concentration necessary for effective haemostasis is unknown; contemporary guidelines recommend a plasma fibrinogen level of 1.5–2.0 g/dl [26].

Historically, TIC has been understood to develop exclusively in response to impairment or loss of procoagulant factors. The identification of ATC led to recognition of the pathological role of anticoagulant and fibrinolytic systems in response to trauma haemorrhage. Brohi et al. first identified a correlation between residual protein C depletion, assumed to be secondary to upregulated activation, and severity of ATC [13]. Subsequent clinical studies have confirmed the early activation of protein C after injury and its association with ATC, increased morbidity and mortality [23, 27, 28]. In a murine model, ATC could be blocked by inhibition of protein C activation using both pharmacological and gene-modulating methods [29]. Interventional clinical studies are required to determine the magnitude of influence this pathway, and other endogenous anticoagulants, has on ATC in humans.

Fibrinolysis is clearly a functional component of ATC. The impressive survival benefit associated with administration of tranexamic acid for traumatic haemorrhage highlights the pathological role of this pathway after injury [30]. Recent prospective clinical studies have better defined the incidence and clinical importance of this entity. Thromboelastometric analysis of 334 major trauma patients (ISS > 15) upon admission to the emergency room identified hyperfibrinolysis in 23, an incidence of 6.8 % [31]. In 14 cases, hyperfibrinolysis was considered fulminant with a complete breakdown of the clot observed within 60 min. A reduction of clot firmness between 16 and 35 % was observed in another nine patients. The mortality rate in patients with fulminant hyperfibrinolysis was 85.7 %, compared with 11.1 % in low-grade fibrinolysis. Patients with hyperfibrinolysis had higher ISS, lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), lower systolic blood pressure and higher lactates than patients without hyperfibrinolysis. Amongst the majority of trauma victims that do not demonstrate hyperfibrinolysis on thromboelastometry, a significant proportion will experience ‘occult’ fibrinolysis with high D-dimers, which correlates strongly with poor outcomes [32].

Platelet counts are mildly reduced by trauma and this appears to associate with poor outcomes. A retrospective cohort study of 389 massively transfused trauma patients reported that in a logistic regression model controlling for ISS, GCS and admission BD, the odds of death at 24 h decreased by 12 % for every 50 × 109/l increase in platelet count [33]. However, in most contemporary studies, they do not decline to levels that may be expected to contribute significantly to coagulopathy [27, 34]. Nevertheless, a few reports have identified that a high ratio of platelets to packed red blood cells is associated with improved outcomes [35]. This may lead us to conclude that the primary platelet impairment provoked by injury and/or haemorrhagic shock is functional. A study of 163 trauma patients has reported a minor, but significant, difference in platelet aggregometry parameters (ADTtest and TRAPtest) between survivors and non-survivors [36].

Vascular endothelium is an active participant in the pathophysiology of ATC. Large capillary beds host thrombomodulin and endothelial protein C receptors anchored through their luminal surface that capture thrombin and accelerate protein C activation 1,000-fold [37]. In addition to inactivating coagulation factors Va and VIIIa, aPC also consumes plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), the major antagonist of tissue-type plasminogen activator tissue type plasminogen activator (t-PA). Consequently, traumatic haemorrhage with tissue hypoperfusion leads to overwhelming release of t-PA from vascular endothelial cells and subsequent hyperfibrinolysis [13].

Fascinating data is emerging, demonstrating an association between tissue hypoperfusion, neurohormonal activation and markers of endothelial disruption [38, 39]. In a prospective study of 75 adult trauma patients, circulating adrenaline levels were elevated in subjects with higher ISS, higher lactate and lower systolic blood pressure. This correlated positively and independently with the incidence of ATC as well as levels of syndecan-1, histone-complexed DNA, high-mobility group box 1, soluble thrombomodulin, t-PA and D-dimers. Trauma haemorrhage has been shown experimentally in rats to cause shedding of the endothelial glycocalyx. Interestingly, this can be prevented by resuscitation with plasma, but not crystalloids or colloids [40]. Endothelial glycocalyx degradation is capable of triggering thrombin generation, protein C activation and hyperfibrinolysis. This is important because it indicates another potential mechanism by which tissue injury and shock mediate systemic anticoagulation early after injury.

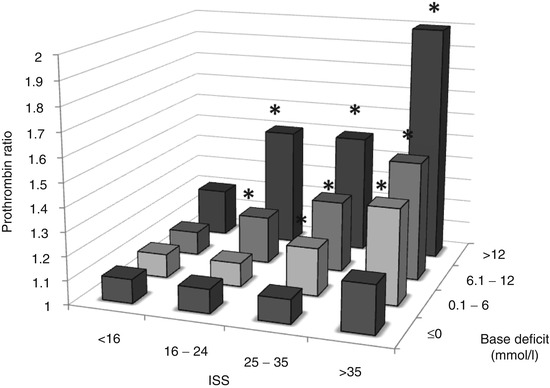

11.4 Diagnosing TIC

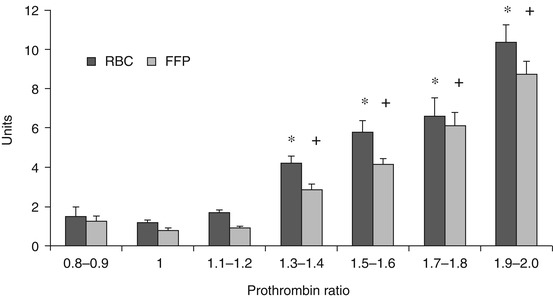

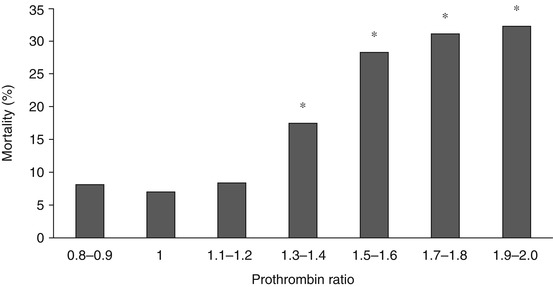

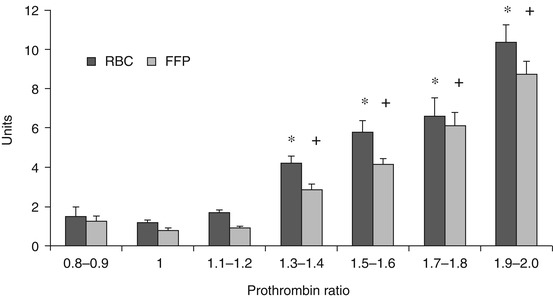

Trauma-induced coagulopathy has conventionally been diagnosed as a prolongation of the international normalised ratio (INR) or aPTT greater than 1.5 times the normal value. However, the evidence for this diagnostic threshold is weak. More recently, the clinical relevance of different magnitudes of TIC has been elucidated (Figs. 11.3 and 11.4), and a prothrombin time ratio (PTr) or INR > 1.2 is now an accepted diagnostic definition of ATC [20].

Fig. 11.3

The relationship between admission PTr and hospital mortality. *p < 0.001 compared with PTr = 1 [20]

Fig. 11.4

The relationship between admission PTr and blood products transfused. *p < 0.001 compared with PTr = 1. +p < 0.001 compared with PTr = 1 [20]

Prothrombin time and aPTT are screening tests that report the time taken for initial fibrin polymerisation of platelet poor plasma, at 37 °C, in response to exogenous stimulation of coagulation. As such they neglect the pivotal role of platelets, do not measure clot strength and may not reflect haemostasis in vivo [41, 42]. Further, they are not reported expeditiously enough to accurately guide transfusion in the acute setting.

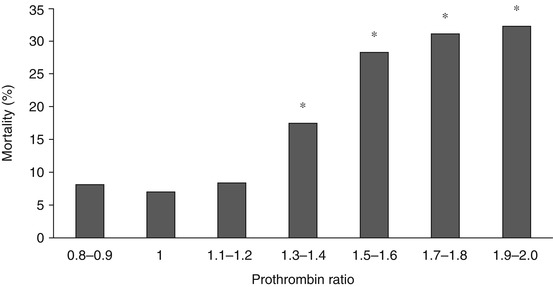

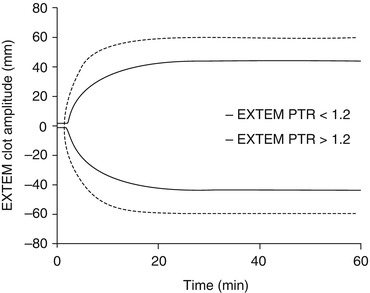

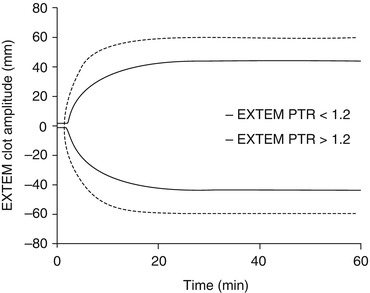

Recently there has been a renewed interest in the use of thromboelastometry for trauma care. These machines (ROTEM and TEG) employ a rotating pin or cup to measure the viscoelastic properties of ex vivo whole blood as it clots inside a small cuvette. They provide an assessment of the speed and strength of clot formation as well as fibrinolytic degradation over time. Research studies suggest their superiority to routine tests of coagulation for diagnosing haemostatic impairments after injury [43, 44]. Trauma patients with ATC (defined as PT ratio >1.2) have a ‘signature’ thromboelastogram (Fig. 11.5). Compared to patients with PT ratio ≤1.2, the ATC trace is characterised by a reduction in clot strength with much smaller changes in clotting times and can be identified within 5 min – threshold of clot amplitude at 5 min (CA5) ≤35 mm (Fig. 11.6) [46]. Future studies using these machines will attempt to identify trace configurations associated with specific coagulopathy phenotypes. Further, they undoubtedly have a potential role in guiding transfusion in real time, and evidence-based treatment algorithms are required to determine our clinical responses to different trace patterns.

Fig. 11.5

The ‘signature’ thromboelastogram of trauma patients with and without ATC. Note clotting times (time to initiation of the curves) are minimally effected. The maximal amplitude (strength of the clot) is the principal difference between the cohorts [46]

Although few patients with ATC demonstrate early depletion of platelets, monitoring the platelet count is useful to identify an emerging dilutional coagulopathy. However, these tests suffer from the same logistical problems as PT and aPTT tests and offer no assessment of platelet function. Platelet aggregometry is not widely available and is too slow to be of use in clinical care. Developments are occurring with viscoelastic tests to enable them to offer a point of care assessment of platelet responsiveness and contribution to clot strength. Given the increased use of platelet inhibitors within the population, this will be beneficial by helping clinicians tailor platelet therapy to individual patient haemostatic function rather than simple counts of platelet number.

11.5 Treating ATC

11.5.1 Conventional Treatment

Conventional trauma-haemorrhage transfusion protocols were developed during the latter half of the twentieth century to guide the delivery of different fractionated allogenic blood products. These guidelines most commonly recommended the administration of packed red blood cells to target a haemoglobin concentration of greater than 10 g/dl after trauma. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) was not deemed required until the INR had exceeded 1.5 and platelets when their number dropped below 50,000 cells/mm3 [47–49]. Hence, it was not considered necessary to replace clotting factors until a dilutional coagulopathy was already established.

An increasing body of evidence developed to indicate that these protocols cannot and do not achieve normal haemostasis in trauma patients requiring a massive transfusion. A study from Houston examined the effectiveness of their pre-intensive care unit (ICU) massive transfusion protocol at correcting coagulopathy in severely injured and shocked trauma victims [50]. Ninety-seven patients receiving 10 or more units of packed red blood cells (PRBC) during hospital day 1 had a mean admission INR of 1.8 ± 0.2. Adherence to their massive transfusion protocol with administration of 5 units of FFP (commenced after the 6th unit of PRBC) together with 12 units of PRBC failed to correct this coagulopathy despite good management of hypothermia and acidosis. By the time of ICU admission 6.8 ± 0.3 h later, coagulopathy persisted (INR 1.6 ± 0.1), and this was identified as an independent predictor of mortality in this cohort.

11.5.2 Earlier and More FFP

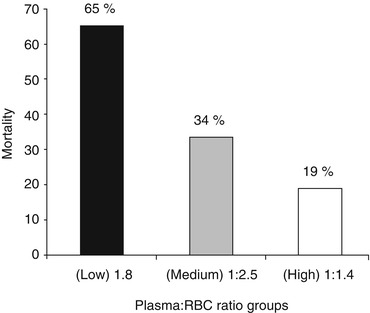

During the first decade of the twenty-first century, data emerged from computer models and observational studies of trauma resuscitation protocols indicating that earlier and more aggressive treatment of coagulopathy with plasma and platelets could improve survival of trauma victims [3, 51]. A landmark retrospective study of the United States Army Joint Theater Trauma Registry analysed the effect of different plasma to red blood cell unit ratios on the mortality of trauma patients admitted to combat support hospitals in Iraq between November 2003 and September 2005 [52]. Two hundred and forty-six patients received 10 or more units of red blood cells (packed red blood cells or fresh whole blood), and they were grouped according to the ratio of plasma to red blood cells transfused. The low ratio group median was 1:8, the medium ratio group median was 1:2.5, and the high ratio group median was 1:1.4. Overall mortality rates were 65, 34 and 19 %, and haemorrhage mortality rates were 92.5, 78 and 37 %, respectively (Fig. 11.7). Upon logistic regression, plasma to red blood cell ratio was independently associated with survival (odds ratio 8.6; CI, 2.1–35.2).

Fig. 11.7

The association between ratios of plasma received by injured soldiers during resuscitation and their risk of death [52]

This remarkable finding prompted clinicians to study their trauma databases to determine whether similar associations were present in the civilian sphere. Multiple retrospective reports flowed in the literature, mostly reporting a positive correlation between the ratio of FFP to PRBC delivered and survival. The first of these was a report by Duchesne et al. in 2008 from New Orleans, which divided 135 massively transfused trauma patients admitted between 2002 and 2006 into those that received a FFP to PRBC ratio of 1:1 and those that received a ratio 1:4 [53]. When the amount of PRBCs was greater than twice the number of units of FFP, a ratio of 1:4 was designated. A FFP:PRBC ratio of 1:1 was assigned to patients who received <2 units of PRBCs per unit of FFP given. Massive transfusion is associated with high mortality and 75 of the 135 cohorts (55.5 %) died. There was no difference in age, male gender, incidence of penetrating injuries, initial systolic pressure and ISS between the two cohorts. A significant difference in mortality was noted in patients with FFP:PRBC ratio of 1:4, 56 of 64 (87.5 %) versus 19 of 71(26 %), p = 0.0001. Patients in the 1:1 group died from ongoing bleeding, 3 of 19 (15.7 %) early after ICU admission within the first day and 16 of 19 (84.2 %) died of multiple organ failure at day 18 ± 12 . In the 1:4 group patients died from ongoing bleeding, 11 of 56 (19.6 %) early after ICU admission and 45 of 56 (80.3 %) died of multiple organ failure at day 16 ± 8. The authors noted that whilst their resuscitation practices addressed the ‘acidosis’ and ‘hypothermia’ components of the lethal triad, it neglected the third factor, coagulopathy. The title of their paper ‘Review of current blood transfusions strategies in a mature level I trauma center: were we wrong for the last 60 years?’ rightly questioned whether the practice of component blood therapy, which is logistically easier than delivering whole blood, was as clinically effective.

Most published studies originated from North American trauma centres, but a few similar reports emanated from Europe and Australia [54, 55]. Not all studies reported data consistent with improved survival from high-dose FFP. For example, a prospective study performed at the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center in Baltimore selected 81 patients receiving a massive transfusion within 24 h (out of 806 trauma admissions) and calculated a logistic regression analysis to determine the effect of FFP:PRBC [56]. No significant effect on mortality was identified for either the PRBC to FFP ratio as a continuous variable (odds ratio (OR), 1.49; 95 % CI, 0.63–3.53; p = 0.37) or 1:1 ratio as a binary variable (OR, 0.60; 95 % CI, 0.21–1.75; p = 0.35) when controlling for age, gender, ISS, closed head injury, laparotomy status and ICU length of stay.

11.5.3 The Optimal Blood Product Ratio

There is a good potential rationale for administering high doses of plasma to patients receiving massive transfusion, as these are the subjects most likely to develop a dilutional coagulopathy. Reports of positive survival benefit with a high FFP:PRBC ratio in studies of non-massively transfused trauma patients are less numerous, perhaps because their procoagulant capacity never becomes diluted below a threshold necessary for satisfactory haemostasis. Further, results of some studies suggest that ‘1:1’ resuscitation is unnecessary and a lower ratio, such as 2:3 or 1:2, could optimise haemostatic support whilst reducing harmful plasma side effects [45, 57]. Regardless, several meta-analyses performed on pooled data have concluded that a high ratio of FFP:PRBC is associated with a significant survival benefit for victims of trauma [58–60].

Prompted by these findings, several groups have performed similar studies looking at the effect of high platelet and/or fibrinogen administration and obtained broadly similar positive results [35, 61]. However, there is inherent survivorship bias in these observational studies that raises doubt on the validity of their conclusions. That is, fresh frozen plasma, which is the predominant source of plasma for most institutions, requires 30–45 min thawing and has conventionally been associated with a delay to administration compared with PRBCs. Therefore, patients with massive and ongoing haemorrhage often die during the early hours of hospital admission before receiving substantial quantities of FFP and thus are included in the low ratio cohort, whereas patients surviving long enough to receive sufficient FFP feature in the high ratio cohort. In other words, perhaps survivors receive plasma rather than plasma producing survivors.

Authors subsequently employed various strategies attempting to eliminate or minimise survivorship bias in their studies. For example, some only included patients who had survived the initial few hours when FFP administration typically lags. However, this strategy sometimes resulted in bias against FFP because early hospital death is frequently caused by rapid haemorrhage and this is the patient group who might be expected to benefit most from plasma. Another method used was to model the relationship between mortality and FFP:PRBC ratio over time and treat the ratio as a time-dependent covariate. Snyder et al. compared mortality of patients who had a high ratio at the end of 24 h with those who had a low ratio and found the former to be associated with increased survival [62]. This advantage became statistically insignificant when they divided the 24 h study period into 0.5–6 h subintervals and calculated the ratio and the mortality rates of both groups within each subinterval.

Obtaining a conclusive answer to the question of optimal blood product ratios to treat coagulopathy using observational studies alone is not possible. A multicentre, randomised trial (PROPPR – Pragmatic, Randomized Optimal Platelet and Plasma Ratios) will compare different ratios of blood products given to trauma patients who are predicted to require massive transfusions. Recruited subjects will receive blood products based on a 1:1:1 or 1:1:2 ratio of platelets, plasma and red blood cells. A total of 580 patients will be enrolled into this study from 12 participating sites in the United States and Canada, and it is estimated to report findings in 2015.

11.5.4 Massive Transfusion Protocols

Some investigators have hypothesised that earlier administration of coagulation delivers survival benefit rather than the precise ratio of products given. Delivering higher volumes of blood transfusion products to rapidly haemorrhaging trauma patients places significant logistical demands upon the local pathology service. Integrated ‘massive transfusion’ or ‘major haemorrhage’ protocols (MHP) have been developed to facilitate and direct the delivery of these products. Riskin et al. performed a 4-year cohort study to assess the impact of implementing MHP, aiming to deliver a FFP:PRBC ratio of 1:1.5 [63]. For the 2 years before and after MHP initiation, there were 4,223 and 4,414 trauma activations, respectively. The FFP:PRBC ratios were identical, at 1:1.8 and 1:1.8 (p = 0.97). Despite no change in FFP:PRBC ratio, mortality decreased from 45 to 19 % (p = 0.02). This was associated with a significant decrease in mean time to first product: cross-matched RBCs (115 to 71 min; p = 0.02), FFP (254 to 169 min; p = 0.04) and platelets (418–241 min; p = 0.01). Effectively, catching up with coagulation support may not be as effective as preventing the impairment in the first place.

11.5.5 Other Haemostatic Agents

Whilst haemostatic resuscitation with a generic formula of blood products is the current practice in the United Kingdom and North America, it has not been implemented universally. Concerns regarding plasma transfusion-related side effects (e.g. immune-mediated adverse reactions, pathogen transmission, transfusion-related acute lung injury), better availability of coagulation factor concentrates and improved utilisation of point of care tests have combined to offer some European trauma centres an alternative, patient-tailored resuscitation solution. For example, in some Austrian centres, resuscitation commences with PRBCs and crystalloids. Recombinant fibrinogen concentrate is then given early to patients who demonstrate impaired fibrin polymerisation on their admission or subsequent viscoelastic test. Platelets are administered to subjects with continued clot weakness despite adequate fibrin function. Prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC, a mixture of recombinant vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors) is supplemented only to those who develop prolonged clotting times on viscoelastic testing (used as a surrogate measure of insufficient thrombin potential). Plasma is rarely indicated in this resuscitation protocol. Some retrospective cohort analyses have associated improved survival and reduced blood product use with this strategy [64].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree