CHAPTER 16 Massage Therapy

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

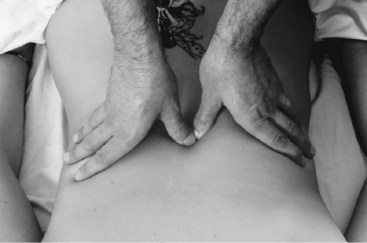

The term massage, in this chapter, is defined as soft tissue manipulation using the hands or a mechanical device. Massage includes numerous specific and general techniques that are often used in sequence; some terms for massage techniques are French in origin. Effleurage (stroking) refers to light, long, slow, soothing strokes along a broad area of the body using the palms and fingers, and is often used at the beginning of the massage. Deeper effleurage can also be used in an attempt to orient vascular or lymphatic flow in a certain direction (Figure 16-1). Petrissage (kneading) uses slightly more force to press and release muscle tissue in circular motions with the stiffened fingers or knuckles, with multiple passes over a small area (Figure 16-2). Tapotement (percussion) is rhythmic, somewhat rapid tapping, cupping, or hacking of a broad area using cupped hands, fists, the ulnar border of the hand, or tented fingers (Figure 16-3). Vibration is a more rapid technique in which an area is covered with flat hands and fingers and shaken or vibrated lightly.1 The term acupressure is used to describe a type of massage technique in which acupuncture points are stimulated manually using the fingers instead of needles; this technique is also called massage acupuncture or Shiatsu massage.2

Figure 16-1 Massage therapy technique: effleurage (stroking).

(From Salvo S. Massage therapy: principles & practice, ed 3. St. Louis, Saunders, 2008.)

Figure 16-3 Massage therapy technique: tapotement (percussion).

(From Salvo S. Massage therapy: principles & practice, ed 3. St. Louis, Saunders, 2008.)

On a broad level, what is often referred to as Swedish massage (SM) is somewhat homogeneous and involves the application of manual therapy using many of the basic techniques described. However, specific types of massage have also been developed, some of which have defined protocols that differ considerably from one another. Common types of massage include SM, Rolfing, reflexology, myofascial release, and craniosacral therapy.3 SM is likely the most common type and combines the basic techniques described earlier. Rolfing involves slow, deep friction massage applied to connective tissue throughout the body to break fibrous adhesions and restore mobility to the fascia. Reflexology uses slow and increasing pressure gradually applied with the fingers to specific points along the hands and feet that are somewhat akin to acupuncture points; reflexology is thought to stimulate specific organs. Deep friction massage involves applying strong, prolonged pressure to a small area of pain (thought to correspond with a trigger point) to temporarily decrease impaired blood flow to that area before releasing the pressure to stimulate reperfusion. Myofascial release involves repeated, slow, deep pressure applied to muscles and connective tissue; a variant of myofascial release in which this pressure is applied while the patient slowly moves the massaged area through its full range of motion is called active release therapy.4 Craniosacral therapy is a gentle form of massage in which light pressure is applied along cranial sutures while deep breathing exercises are performed.5 Traditional Thai massage (TTM) for low back pain (LBP) is a deep massage with prolonged pressure for usually 5 to 10 seconds per point on low back muscles between L2 and L5.

History and Frequency of Use

Massage may be the earliest and most primitive tool to treat pain.6 The most ancient references to the use of massage come from China (around 2700 bc), India (around 1500-1200 bc), Babylonia (around 900 bc), Greece (Hippocrates 460-377 bc, Asclepiades, Galen), and Rome (Plato 427-347 bc and Socrates 470-399 bc).7,8 Massage appears to be gaining popularity in recent years as increasing numbers of people with chronic low back pain (CLBP) are seeking complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). A survey of CAM use among the general adult population in the United States conducted in 1991 reported that massage had been used by 7% of respondents in the past year.9 Massage was the third most commonly reported CAM therapy after relaxation techniques (13%) and chiropractic (10%). However, only 41% of those who reported using massage had consulted with a health care provider; others presumably received informal massage from family or friends or performed it themselves. The medical conditions for which massage use was highest were back problems and sprains or strains. When this survey was repeated in 1997, the use of massage in the previous 12 months had grown to 11% and was still the third most common CAM therapy, this time after relaxation (16%) and herbal medicine (12%).10 Among those who reported using massage, the proportion that saw a professional practitioner was increased to 62%. The total number of visits to massage practitioners in 1997 was estimated to exceed 113 million. The medical conditions for which massage use was highest were back problems, neck problems, and fatigue. A prospective study of CAM use among 1342 patients with LBP who presented to general practitioners in Germany reported that 31% used massage in the subsequent 1 year follow-up.11 The use of massage was statistically significantly higher among those with CLBP, with an odds ratio of 1.6 (95% CI, 1.1 to 2.3). Massage was the most commonly reported CAM therapy. A survey conducted by the American Massage Therapy Association reported in 2008 that 36% of respondents had received a massage in the last 5 years.12

Procedure

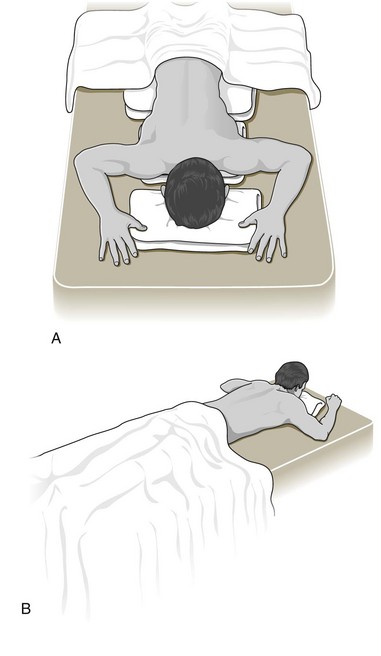

To begin an individual massage therapy treatment, the practitioner will leave the treatment room (if the patient does not need help getting on or off the massage table), and will ask the patient to prepare for the massage by removing clothing as required for optimal treatment (and as is comfortable for the patient). They will then lie or sit on the massage table or chair, as requested, and be covered by a sheet or blanket (Figure 16-4). Only the parts of the body that the patient has consented to have treated are uncovered to respect the patient’s modesty. A competent provider will adapt to the patient’s preferences and treatment needs for positioning and draping. Massage for LBP is often conducted with the patient in the prone position, but this can (and should) be modified if the patient is unable to remain in this position comfortably or to help the therapist access areas to be treated.

Theory

Mechanism of Action

At its most basic, massage therapy can be viewed as a simple way to aid in relaxation, promote a sense of well-being, and ease feelings of muscular tension, all of which may ultimately lead to decreased pain and improved physical function. The mechanism of action for massage therapy is not fully understood. It is thought to achieve its results through a complex interplay of both physical and mental modes of action. Massage therapy delivered to soft and connective tissues may induce local biochemical changes that modulate local blood flow and regulate oxygenation.13 These local effects may subsequently influence neural activity at the spinal cord segmental level, thereby modulating the activities of subcortical nuclei that influence both mood and pain perception.14

Massage therapy may also increase the pain threshold at the central nervous system (CNS) level by stimulating the release of neurotransmitters such as endorphins and serotonin. It may also act through the gate-control theory of pain, which proposes that local stimulus (e.g., massage therapy or other interventions) to an affected area stimulates large-diameter nerve fibers, which inhibit T-cells in the spinal cord that project into the CNS, then followed by pain relief.15 Massage therapy has also been proposed to increase local blood circulation, improve muscle flexibility, intensify the movement of lymph, and loosen adherent connective tissue.6 These actions may alternately improve reuptake of local nociceptive and inflammatory mediators, increase pain-free range of motion, and improve muscle function.

Indication

Massage is indicated for a wide variety of conditions, including CLBP, in which pain relief, reduction of swelling, or mobilization of adhesive tissues is desired.6 It is uncertain which patient characteristics are associated with improved outcomes for massage therapy in CLBP. The general profile of patients included in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting positive outcomes for benefit of massage was adults (18 years and older) with nonspecific CLBP and without infection, neoplasm, metastasis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, fracture, inflammatory process, or radicular syndrome. Prior studies have reported that gender, race, work status, and family income did not influence the outcomes obtained with massage therapy.16

Assessment

Before receiving massage therapy, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. The massage therapist should also inquire about general health to identify potential contraindications to this intervention. Diagnostic imaging or other forms of advanced testing is generally not required before administering massage therapy for CLBP.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found low-quality evidence to support the efficacy of massage therapy in the management of CLBP.17

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found limited evidence that massage, when combined with exercise and brief education, is more effective than massage alone, exercise alone, or sham laser therapy, with respect to short-term improvements in pain and function.18 That CPG also found limited evidence that massage is more effective than exercise, brief education, acupuncture, relaxation training, or sham massage with respect to short-term improvements in pain and function. There was limited evidence that massage is as effective as SMT, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), or a corset, with respect to improvements in pain. That CPG also found limited evidence that massage is less effective than TENS with respect to improvements in pain. There was limited evidence that massage is less effective than SMT with respect to improvements in function. That CPG did not recommended massage for the management of CLBP.

The CPG from Italy in 2007 did not recommend massage for CLBP.19

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found limited evidence to support the efficacy of massage with respect to short-term improvements in pain and function.20

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate-quality evidence to support the efficacy of massage for patients who do not obtain adequate pain relief with self-care alone.21

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 16-1.

TABLE 16-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Massage Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | Belgium | Low-quality evidence to support use |

| 18 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 19 | Italy | Not recommended |

| 20 | United Kingdom | Limited evidence to support use |

| 21 | United States | Moderate evidence to support efficacy |

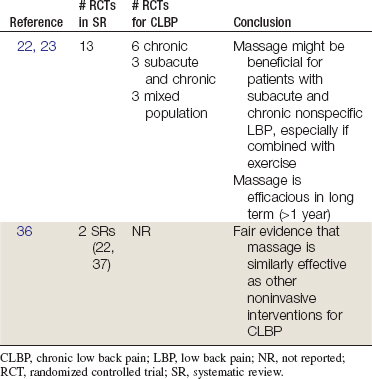

Systematic Reviews

Cochrane Collaboration

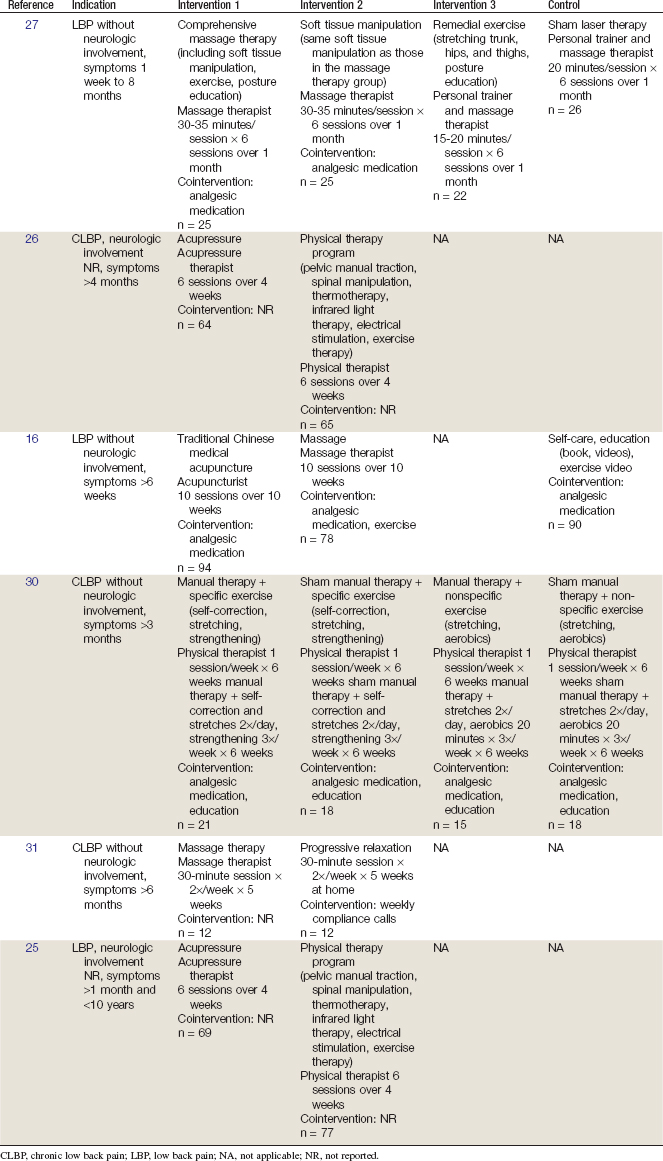

In 2008 the Cochrane Collaboration conducted an SR on massage for nonspecific LBP.22,23 A total of 13 RCTs were identified, including 1 RCT on acute LBP, 3 trials of subacute and chronic LBP, 6 trials for CLBP, and 3 trials of mixed LBP duration.16,24–35 The review concluded that massage might be beneficial for patients with subacute and chronic nonspecific LBP, especially if combined with exercise and delivered by a licensed therapist. Massage was shown to be efficacious in the long term (at least 1 year). One study showed that acupuncture massage was better than SM, and another trial showed that Thai massage is similar to SM, but these findings were not confirmed.28,29

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2007 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic LBP.36 That review identified two SRs related to massage therapy and LBP, including the Cochrane Collaboration review mentioned previously.22,23,37 The review found consistent conclusions between the two SRs. They found that there was not enough evidence to evaluate the efficacy of massage in acute LBP and that there was fair evidence that massage is similarly effective as other noninvasive interventions for CLBP. This review did not identify any additional RCTs.

Findings from the above SRs are summarized in Table 16-2.