Management of Warts

Peter C. Schalock

Arthur J. Sober

Warts result from skin infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). They can be cosmetically bothersome and occasionally a source of pain. Cervical involvement with some strains of the virus can lead to cervical cancer (see Chapter 107). Nongenital warts affect 7% to 10% of the general population and are among more commonly seen dermatologic problems in primary care. The primary care physician should be able to distinguish warts from other skin tumors, select effective treatment, and educate the patient in proper self-care and prevention.

Pathophysiology

HPV is a double-stranded DNA virus, with more than 118 types identified. It is epitheliotropic and causes tumors of the epidermis. Multiple types are oncogenic (HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, and 59), implicated in cervical carcinoma (see Chapter 107) and squamous cell carcinoma (see Chapter 177). HPV types 6 and 11 are implicated in lower-risk anogenital warts. Warts can be transmitted by direct contact, autoinoculation, or, rarely, from a fomite. Young people have a high frequency of warts, which occur most commonly between the ages of 12 and 16 years. Resolution can occur spontaneously, presumably through immunologic mechanisms. Approximately three fourths of warts disappear spontaneously within 2 years of their appearance, but if they are left untreated, additional warts may develop from the original ones.

Clinical Presentations

Clinical presentations vary according to site and viral strain involved. Morphologically, nongenital warts appear in three forms: the keratotic common wart, the filiform wart, and the flat wart. Most warts are asymptomatic; however, a plantar wart can be the source of considerable pain, acting as a foreign body during weight bearing. Anogenital warts may become friable, bleed, and cause discomfort. Periungual lesions may become fissured and destroy the nail matrix and nail bed.

Common Warts (Verruca Vulgaris)

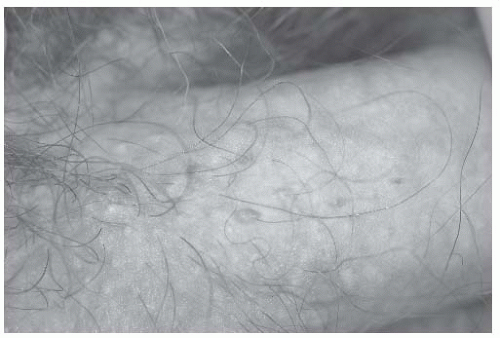

The common wart (verruca vulgaris), associated with HPV-1, HPV-2, HPV-4, HPV-27, or HPV-57 infection, appears flesh colored or grayish white with a papillate, hyperkeratotic surface. The wart may be punctuated with black dots that represent thrombosed superficial capillaries (Fig. 194-1). The common wart may appear anywhere, but frequently affects the elbows, knees, fingers, and palms. The filiform wart is more delicate and threadlike. The flat wart (verruca plana), caused by HPV-3 and HPV-10, is smaller than the common wart. Flat warts are tan-to-flesh-colored, slightly raised papules with a relatively smooth surface. Great numbers of them may appear on the hands, in beard areas, and on the shaved legs of women. Flat warts are easily spread and occasionally present in a linear arrangement.

Plantar Warts (Verruca Plantaris)

The plantar wart (verruca plantaris) results from infection of the plantar surface of the foot with HPV-1 or HPV-4. It appears as a small skin nodule that produces grayish or yellow interruptions in the skin lines (dermatoglyphics) of the foot (Fig. 194-2). It is less elevated than other warts because weight bearing presses it inward. These warts may be solitary, multiple, or confluent; if they are confluent, the term mosaic wart is used.

Genital Warts

In the genital area, four clinical morphologic types are seen: the cauliflower variety (condyloma acuminatum); smooth, flesh-colored papular lesions (Fig. 194-3); flat warts; and keratotic genital warts, which can mimic seborrheic keratosis. Anogenital warts, lesions at low risk for dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma, are derived from the sexual transmission of HPV-6 or HPV-11 and grow on mucous membranes. Lesions that are at high risk for cancer are derived from infection with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, or HPV-59. Anogenital warts range in appearance from pinpoint to cauliflower-like. Elevated, lobulated papular lesions correlate with HPV-6 and HPV-11, whereas the flat, hyperpigmented types are high-risk lesions

associated with HPV-16 and HPV-18. Coexistent sexually transmitted diseases are common (see Chapter 141). Mucocutaneous warts may become refractory to treatment (see later discussion).

associated with HPV-16 and HPV-18. Coexistent sexually transmitted diseases are common (see Chapter 141). Mucocutaneous warts may become refractory to treatment (see later discussion).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Common warts should be differentiated from squamous cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, and a cutaneous horn arising from an actinic keratosis (see Chapter 177). The differential diagnosis also includes Gottron papules (seen on the dorsal aspect of the fingers in dermatomyositis), granuloma annulare, lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, skin tags, epidermal nevus, and lichen nitidus. Other lesions that patients may mistake for warts include digital fibrous tumors and mucous cysts. Multiple flat warts on the face should be differentiated from trichoepithelioma, syringoma, and the cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis.

Anogenital warts must be differentiated from the condyloma latum of syphilis and from squamous cell carcinoma. The differential diagnosis also includes pearly penile papules, ectopic sebaceous glands (common after circumcision), and nevi. Bowenoid papulosis (associated with HPV-16) appears as pigmented wartlike lesions on the male and female genitalia and is a form of carcinoma in situ, although it has little biologic tendency to behave aggressively.

WORKUP (2)

The appearance is usually sufficient to indicate the diagnosis, but early genital warts can be difficult to identify. Typically, a patient comes for evaluation because warts have been found in a sexual partner. In a male patient, the penis and upper portion of the scrotum should be carefully examined. If no visible lesions are present, acetic acid can be used. Soaking the penis for 5 minutes with a gauze moistened with 5 % acetic acid (white vinegar) demonstrates early lesions not previously evident. For the gynecologic examination, early warts are best demonstrated when they are made white with acetic acid. The colposcope provides magnification if necessary. However, one must remember that the use of acetic acid is very nonspecific; any disease or lesion that alters the stratum corneum will turn white with acetic acid.